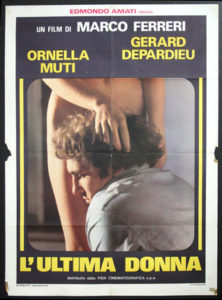

La dernière femme (1976)

Director: Marco Ferreri

„If I were asked to characterize the present state of affairs, I would describe it as ‘after the orgy’. The orgy in question was the moment when modernity exploded upon us, the moment of liberation in every sphere. Political liberation, sexual liberation, liberation of the forces of production, liberation of the forces of destruction, women’s liberation, children’s liberation, liberation of unconscious drives, liberation of art. The assumption of all models of representation, as of all models of anti-representation. This was a total orgy- an orgy of the real, the rational, the sexual, of criticism, of development as of the crisis of development. We have pursued every avenue in the production and effective overproduction of objects, signs, messages, ideologies and satisfactions. Now everything has been liberated, the chips are down, and we find ourselves faced collectively with the big question: WHAT DO WE DO NOW THE ORGY IS OVER?“

Jean Baudrillard, The Transparency of Evil

***

Marco Ferreri films are dealing with various states ‘after the orgy’. In his most acclaimed film, La Grande Bouffe (The Big Feast, 1973), bored decadence was elegantly pushed to its extreme when a group of men go to a mansion in the French countryside where they plan to eat themselves to death, the criticism on modern day decadence culminating in the ultimate decadent act: eating a cake made of pure shit. I was fortunate to grew up in a country that didn’t ban or censor such films but frequently aired them on TV, and so I was left inconsolable after having caught the film by chance on late night TV as a teenager – Marcello Mastroianni’s death was one most beautiful and sad things I had ever seen, and felt. Executed by free artistry and wild imagination, the appropriately perverse masterpiece shows the collapse of a miniature consumption society.

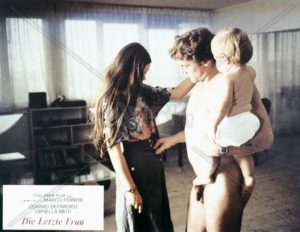

While La Grande Bouffe dealt with general decadence and its inevitable parasite called ennui, La dernière femme (The Last Woman) dissects the dark side of the liberation of morals after 68 and one specific proliferation of the modern orgy: Western feminism, or what we call the “battle of sexes” in the absence of truly heroic struggles. Gérard (Gérard Depardieu) is left by his wife Garielle (Zouzou) for reasons of feminist liberation and the search for her Self, and its being hinted at that she has turned into a lesbian for the same reasons, leaving her 9-month-old son Pierrot behind in the sole custody of his father. Gérard seems unaffected and arranges with the situation, taking care of the baby with maternal passion and without ever complaining, while maintaining some loose sexual affairs to mistresses. The engineer is laid off from work when he meets his last woman, Valerie (Ornella Muti), who changes nothing and everything, all culminating in one of the most shocking and mythical final scenes in cinema history.

Don’t expect a sentimental arthouse substitute like Kramer vs. Kramer with the ultra-annoying Dustin Hoffman now- Depardieu is in another league. A highly educated and nuanced force of nature who is built like a truck driver and lacks all pretense and pettiness, Depardieu gives one of his trademark early performances of appealing coarseness with underlying delicacy and subtleness. Blessed with a past as robber, thief, and male prostitute, it is a spectacle to watch the levels of naturalness and personal freedom which Depardieu exhibits when running around not only naked but with an erection for half of the film, and in his cultivation of unaesthetic grunts and groans in an artistic performance that lacks all vanity.

and lacks all pretense and pettiness, Depardieu gives one of his trademark early performances of appealing coarseness with underlying delicacy and subtleness. Blessed with a past as robber, thief, and male prostitute, it is a spectacle to watch the levels of naturalness and personal freedom which Depardieu exhibits when running around not only naked but with an erection for half of the film, and in his cultivation of unaesthetic grunts and groans in an artistic performance that lacks all vanity.

Naturalness is important here, since in La dernière femme nature has been cemented over. Marco Ferreri has embedded his film in an entirely grey, brutalist landscape composed of modern factories, highways, and high-rise housing complexes. Gérard is stuck in this unnatural landscape and moves like a panther on the concrete in it, and his naked body serves as an astonishingly effective contrasting special effect in this context. It is exceptional. Along with the symbolic landscape, other subplots suggest that things are out of balance, and masculinity in crisis: not only is the mother of his baby missing, but the engineer Gérard is laid off from work, a fact that goes almost unnoticed in the film because of the nonresponse of Valerie or his ex-wife to this crucial development. Gérard never publicly worries or complains, and it is only in a moment of solitude on his balcony where he watches the life on the street and resents, “Everybody is buzzing around, living, working… I am being excluded.”

Valerie invades Gérard’s private life like a guest who doesn’t know when to leave. Gérard doesn’t ask or push her to move in, and he also doesn’t play any games of domination and submission to build up emotional dependancy. Their relationship is one of those triste alliances on the fringes of human existence, a random collusion that bears nothing touching or romantic. Liberated things happen, like Valérie calling her ex Michel and going off to see him all night. When she returns to Gérard’s flat, he doesn’t get verbally or physically aggressive but dismissive, insisting on masturbating in front of a mirror instead of making love to her. Gérard doesn’t love Valerie, nor does she love him. Valerie still turns the sexual affair into a strange domestic life where she immediately takes over the role of the mother, a fact that Gérard comes to resent, also fearing another potential disappointment for his maternally abandoned child. This lingering threat gains more traction when his feminist wife and her new girlfriend visit them, observing the new constellations in the house with scientific coldness, as if the life of her abandoned son- whom she not once touches- was an educational and psychological study. Valerie is impressed by the feminist and the passionless academic attitude Gabrielle eludes, and while the women are talking about simple educational concepts and books, the engineer Gérard builds an impressive and manoeuvrable wooden cannon for his boy in the next room. It is a symbolic scene which brilliantly exaggerates the differences between the sexes, but also highlights the destructive similarity between the inventories of the modern man and woman: it are weapons of mass-destruction, one loud, crafted, and tangible, the other intangible and taking place in thoughts and ideologies.

Gérard Depardieu is childish and loutish like many of Ferreri’s other heroes as he rants and raves about his obsession with his and his baby son’s penis, prancing around his flat like a giant baby himself. While we rightly find this phallic obsession to be at least funny and eccentric, if not ridiculous and pathetic, it dawns on us that Valerie will soon do the same humorlessly if she succumbs to Western feminist doctrine: “embrace your femininity, your vulva is a flower, the entire world is a mother-orchid-vulva,” etc etc. Ferreri tells us a truth about the modern world, that of the indomitable duality of all things, in this particular case the duality of the liberation of female sexuality and suppression of male sexuality.

as he rants and raves about his obsession with his and his baby son’s penis, prancing around his flat like a giant baby himself. While we rightly find this phallic obsession to be at least funny and eccentric, if not ridiculous and pathetic, it dawns on us that Valerie will soon do the same humorlessly if she succumbs to Western feminist doctrine: “embrace your femininity, your vulva is a flower, the entire world is a mother-orchid-vulva,” etc etc. Ferreri tells us a truth about the modern world, that of the indomitable duality of all things, in this particular case the duality of the liberation of female sexuality and suppression of male sexuality.

Valerie is as absurdly passive and indifferent as she is voluptuous and beautiful, and her passiveness doesn’t spare her sexual life. She repeatedly asks Gérard to be tender although it so very obviously doesn’t match his impetuous temper and vital nature, and although he lusts for her and tries to, she remains cold. But Valerie doesn’t reflect on her overall phlegm (which is only once broken when she attacks Gérard with a hammer), instead she tells Gérard that he never succeeds in giving her an orgasm. It is here where the change of focalization and hypocrisy in modern discourse is marked, and it feels quite surreal and revealing. To flip around the narrative while staying within its very vocabulary: in La dernière femme we see a man who is empowered, sexually active and in confident harmony with his body, yet abused by a female phlegm around him that channels itself in an unintellectual and hypocritical ideology which fires with the very weapons it claims to reject in order to appear stronger. Gérard begins to feel excluded as a father and a man, and he feels reduced to his sexuality alone when Valerie persuades him that his sex is the root of his egocentricity. “You are nothing without it,” she says, which prompts Gérard to make the ultimate gesture to prove her wrong by slicing off his cock with an electric knife.

Earlier, with his baby’s penis in his hands, Gérard ponders, “All we are left with is the right to go around sporting one of these. But now they want to take away our pride in having them – we’re not even allowed that anymore! So what are we supposed to do with them now?”. A look into the Far West in 2021 might provide an answer: suicide in Northern America is dominated by white men, who account for 70% percent of all 50000 cases, a number almost 4 times higher than the number of women dying by suicides, and 150 times higher than the number of femicide in the country (238). It is likely that not a few of these male suicides are caused by the same senses of loss that Gérard is experiencing: the loss of work and purpose due to liberated markets, and the loss of family and a balanced and natural masculinity in the hyper-feminist discourses of the West. 45 years ago, Ferreri gave us important clues about the direction we are heading with his La femme dèrniere, a piece of art that is utterly complete aesthetically and in its social commentary. Unfortunately, the film was banned due to sexual frankness and nudity mostly everywhere outside of Europe, including the US- a country that at the same time was in the process of establishing the biggest hardcore porn industry in the world.

***

„WHAT DO WE DO NOW THE ORGY IS OVER? Now all we can do is simulate the orgy, simulate liberation. We may pretend to carry on in the same direction, accelerating, but in reality we are accelerating in a void, because all the goals of liberation are already behind us… we live amid the interminable reproduction of ideals, phantasies, images and dreams which are now behind us, yet which we must continue to reproduce in a sort of inescapable indifference.“

by Saliha Enzenauer