Barış Manço: The King of Anadolu Psych

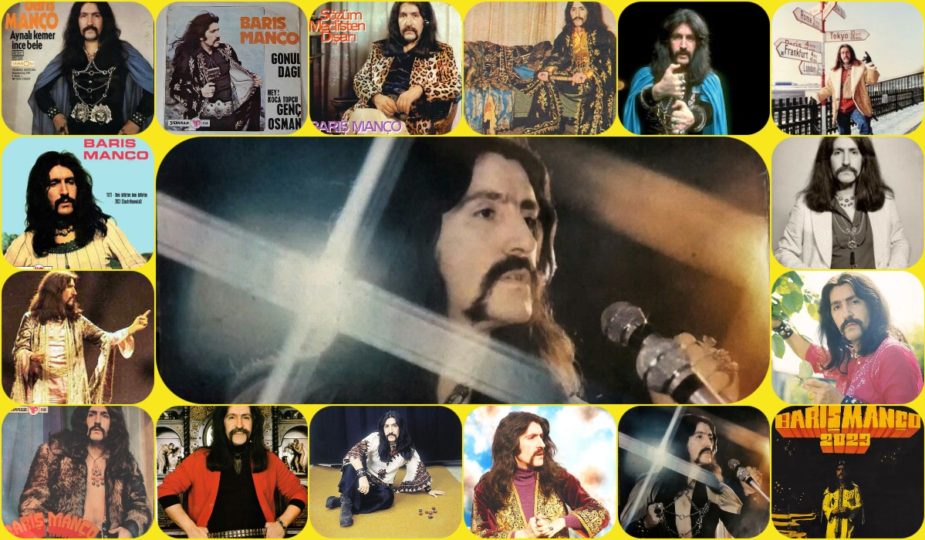

In this episode of Crazy Turks, we talk about the unquestionable king of Anadolu Rock & Turkish Psychedelic, the great Barış Manço. Outside of Turkey the perception of Manço seems to start and end with his 1975 prog-voyage 2023, an album that is not among his most popular ones in Turkey and really not the best one of his career that spanned from 1962 to 1999. While this article will focus more on his persona and legacy than reviewing particular music by Manço, his albums Yeni Bir Gün (1979), Sözüm Meclisten Dışarı (1981) and Estağfurullah… Ne Haddimize! (1983) can be recommended as good starting points to discover the Turkish legend’s music.

Barış Manço got marked as an original right upon his birth on 2 January in 1943 in WW2-Istanbul: after his older brother had been named ‘Savaş’ (“war”) two years earlier, Mehmet Barış Manço was given a middle name that literally translates to “peace”, and he was officially the first person in Turkey to be given that name, before it went on to become a very popular unisex name in the country. And indeed, Barış Manço highlighted in his art values such as peace, love and tolerance, and steered people towards the good and the beautiful with his humanistic stance; and therefore became one of Turkey’s most precious treasures.

Barış himself also used dichotomous names for his two sons, who carry the names Doğukan (“blood / ruler of the East”) and Batıkan (“…of the West”), two names that also reflect Manço’s musical style between a Western rock tradition and Turkish folk, a style born out of Turkey’s unique position between East and West that echoes in many of Manço’s lyrics. Manço acted as a bridge between tradition and modernity, an artist with a vision to build a future without the assimilation of native and national values. Although rooted in Turkey, Manço thought and acted in global terms and thus not only immensely contributed to the promotion of Turkey’s but the world’s cultural richness.

Although a world-renowned artist, Manço’s greatness and impact is not fully understood outside of Turkey. He was more than a groundbreaking musician and early pioneer of rock’n’roll, anadolu psych and disco who was influential until the day he died. Barış Manço was probably even more successful with his long-running TV-Show 7’den 77’ye in the 80’s and 90’s, a mix between a children’s show („Because they are our future and I have to look out for them“), and reportages where he traveled every city in Turkey and visited over 150 countries on all continents, introducing them to the Turkish people and educating them on regional cultures. Imagine: an extremely cultivated and educated, eccentric long-haired hippie who graduated at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Belgium who’s bringing the world into the living rooms of millions of people and making them see the world through his sophisticated gaze. I attribute a good portion of my global perspective on things to Manço’s influence. Moreover, most of my immigrant working-class friends from Jugoslavia, Poland, Russia, and South America were also listening to his music and watching his shows with their families via satellite or cable- this was a parallel world unknown to Germans.

The Turkish were very spoiled with Manço, which doesn’t mean that they didn’t know what they had in him. Manço had plans to become the Turkish president: „I do not want to enter the Parliament of Turkey by running for a political party. I hope that changes to the constitution will be made and the president will be elected by the people in the 2000s. Then I would like to announce my candidacy and if the people support me, I would like to become president.” There was little doubt that Manço would have won with a vast majority, so immense was his popularity and authority among the Turkish people. But Manço died before the dream came true and without seeing how the Turkish government finally changed the parliamentarian vote into a popular one in 2007. His sad, untimely death by a heart attack with just 56 in 1999 caused a unanimous shock and buried Turkey collectively in grief and tears. From children to old people, everybody mourned the loss of this national treasure, and political conspiracies emerged surrounding the death of the country’s future supreme patriarch.

In his book The Turkish Psychedelic Explosion: Anadolu Psych 1965-1980 (2018), Daniel Spicer visits Manço’s house, which is now a museum, and describes the artist’s private basement studio: „Back down again, and we descend into the basement, a gloomy dungeon with custom-made stained glass windows giving blindly onto lightless, subterranean depth, installed especially by Manco to suit this gothic space. Bullwhips lie coiled like snakes in cases, hinting not at sexual games but firm, unquestioned masculine power. These are the trappings of a patriarch at rest.“ The point about the firm, unquestioned masculinity that applies to Manço is an important and interesting one that gets rarely discussed, although it is just as attractive as a confident female sexuality. In popular western culture, masculinity is more often to be found within cinema than in other arts, almost as if masculinity is an unnatural feature that cannot be united with the fine arts and intellectuality, and one that is abandoned to exaggerated and cartoonish depictions in genres like Western or Action which seem to function as a concentrated compensation. Here was a man very confident with his sexuality and indeed singing about that sexuality constantly without being vulgar or macho, because Manço paired it with sultry romanticism and was fluent in the codes of folk narratives with their rustic and playful eroticism. His song “Lambaya Püf De!” got temporarily banned for obscenity by the military government after their coup in 1980, because a heated Manco is basically having an orgasm on tape while obsessing on instructing his lover to turn off the lights, sit down on him, go slower, not so fast, a bit slower girl… In the sanitized version, hens cackling like madwomen do the singing instead of Manço – brilliant.

Because of confident, larger-than-life men like Barış Manço and the other Anadolu Rock stars, wearing longer hair on men was much more accepted in Turkey than you might think, because it was not negatively associated to being a drug-hippie. Or take Manço’s fantastic, eccentric clothes and jewellery, most famously his ornate, beaded Kaftans. Manço’s references were the glorious robes of emperors, reminiscing the display of splendor by Sultans and wearing the crescent in his mustache like a Mongolian emperor rather than playing with travesty and masquerade. Elvis Presley can be considered the bridge from the other side of these two different worlds, East and West. In the end, it was a way for both artists to say: “I am a true king”.

Another parallel to Elvis is the accomplishment of the mandatory military service. Manço released his first single in 1962, and until 1969 was singing mostly in English language and for the European market. In 1970 he released his first single that was not just bound to rock’n’roll anymore, but used traditional Turkish instruments. “Dağlar Dağlar (Mountains Mountains)” won him platinum and sky-rocketed his career in Turkey for the next two years, where he released hit after hit with the Moğollar and Kurtalan Ekspress bands. In 1972, at the first peak of this success, Manço interrupted his career for the military service- Manço and all of his other mates from the Anadolu Rock scene like Cem Karaca and Erkin Koray served for almost 2 years. These artists saw it as no contradiction to their left-wing views and quest for peace and social justice. Moreover, all of them later expressed how important and formative the army years had been for them, connecting them to the country and its people while being stationed at rural outposts of the military. All of them used more traditional folk influences in their music after their military experiences and embraced both their masculine and feminine sides.

Manço’s self-confidence enabled him to write about a large variety of topics: one day it could be the most beautiful and tender love song, or sultry, erotic meltdowns at chicken coops or mountain tops, at other times Ottoman-battle-cry funk, the pan-Turkic epics of 2023 or nuclear bombs going off in his anti-war children’s tunes. Often fathoming the Eastern and Western influences that come together in a unique way in the country, the results are Chekhovian moral portraits of the multi-ethnic Turks, elaborate tales that pushed the boundaries of a mini-format like the song. With the respect and trust given to him, Manço often used his authority in bold ways and successfully walked the thin line between educating and insulting the people. His songs not only talk the language of a man in love with his country and its people, but one that also criticizes and challenges when necessary. In “Rezil Dede (Shameful Grandpa)”, he sides with a delicious female mob and shames old men craving for young girls, rolling sentences like „Go old man, and send your son“ from the mocking tongues of strong young ladies- it takes a man to shame a man. In “Ayi (Bear)”, he controversially compares ignorant rural people to bears, a Turkish insult to label somebody a uncultivated redneck. The song is complete with a psychedelic set up of a visit to those bears in the zoo where Manço explains to the children: „Look son, they call this a bear. They come down from the forest to the city…” While I understand why Hillary Clinton called certain Trump voters “deplorables” – every society is rich of deplorables- she certainly didn’t have the intellectual and moral authority to say such a thing as the highly corrupted politician that she is, and therefore rightly got punished for it. Manço went even further and called the deplorables “animals”, but he offered a hand to those he criticized and advocated for co-existence and progress, not division: „Of course we need animal love / but everything is mutual / You have to respect me so that I can respect you...”. Manço performed the miracle that the criticized exercised in self-reflection and eventually agreed with him more often than not.

Barış Manço is deeply missed but never forgotten, as his legacy still lives on strongly in Turkey 23 years after his death. But the bitter truth is that if Manço had lived long enough to become the Turkish president, his artistry would likely be dismissed in favor of a political misrepresentation and demonization of his persona & ideas that challenge the unjust colonial world order, which is now in its dementia stage. But not just Turkey- the world is badly in need of fantastic men like Barış, and peace.

by Saliha Enzenauer

Barış Manço World Tour- a playlist