Gritty Poetry of Wanda Robinson

Wanda Robinson was born on November 18, 1949 in Baltimore, Maryland during the same year as Gil Scott-Heron who became a chronicler of African American culture and a fierce critic of politics, society, and the U.S. government, an innovator with his rhythmic poems anticipating hip-hop/rap. During the same years when Gil Scott-Heron released his albums Pieces of a Man and Winter in America, Wanda Robinson released her albums Black Ivory & Me and a Friend. While Gil Scott-Heron is still acclaimed (most famous for his “Revolution Will Not Be Televised”), Wanda Robinson fled the limelight. Her unfortunate vanishing has meant that her records have remained rather obscure and unsung.

At the young age of 21 in 1970, Wanda Robinson recorded her debut Black Ivory which was released the following year. The album featured poems about black culture (“John Harvey’s Blues”), community (“Grooving”), and relationships (“A Black Oriented Love Poem”) and contains improvisatory jazz music and an overall optimistic tone (“Celebration – Read Street Festival”, “Good Things Come”).

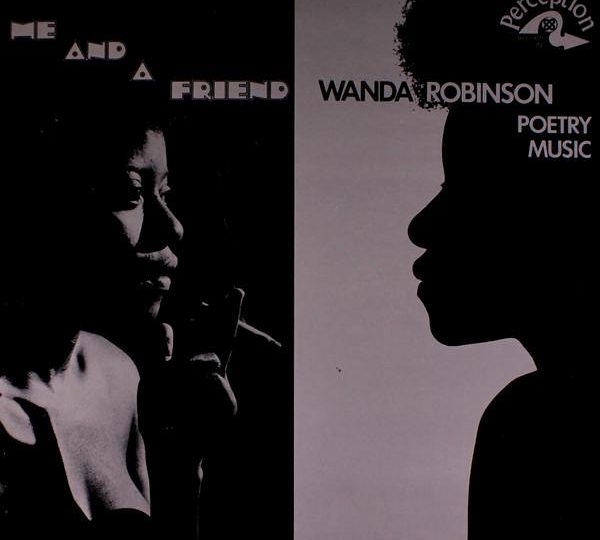

At the age of 22, only one year later, during the autumn of 1971, Wanda Robinson’s mood and outlook had darkened and grown pessimistic (“Nobody in His Right Mind”, “Because They Envy Us”, “My Father is Dying”, “Paranoia”, “The Un-Hero”) as she recorded readings of a new selection of her poems. At the age of 23, in 1972, she changed her name to Laini Mataka, shaved her afro, and abandoned this second project. The label Perception that had released her debut was left without their performer or musicians for her to collaborate with. They contacted the arranger Julius Brockington who listened to Wanda Robinson’s readings and then recorded music with himself on organ/piano, Gary Langston on guitar, Marcell Turner on bass/tambourine, Ralph Fisher on drums, Steve Turner on alto sax/flute, and Jim Wilson on trumpet. The result? The more complex and dynamic Me and a Friend.

Although the album contains only eight of Wanda Robinson’s poems and a running time of 34 minutes, her strong voice shines through this half-hour of mesmerizing music. The first two songs, “A Possibility (Back Home)” and “Carnal Was the Word” are about African pride, female empowerment, love, romance, and sensuality that share a similar spirit as the songs on Black Ivory. Julius Brockington’s arrangements do not always work. For example, on the third track, “Nobody in His Right Mind”, Wanda’s poem opens with a commentary on the death of the 1960s movement after the assassinations of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King, Jr. (“nobody in his right mind is peace and love these days, ain’t it strange to find your dream lying in the gutter with its insides torn out… most of the wars are being waged against us, when a cracker talks of peace, he means peace in the grave and when he talks of love, he means how he’d love to help us get there”), but Brockington’s music is oddly upbeat. And on the fourth track, the band has jams two minutes before Wanda begins her poem about American capitalism and white supremacy (“they drench our foods with poisons, fill our veins with drugs, and our eyes can no longer see what our ears refuse to hear… our minds no longer rage” and three minutes afterwards. “My Father is Dying” is her memorable poem about her father’s mortality.

“Odyssey/The Feelin’” is the slowest and smokiest song, starting side two with melancholy, mournful, nocturnal jazz as she is “lighting incense, burning candles, and praying to every god in African mythology”). She bluntly confesses she’s “ridiculously horny”, a moment of comic honesty. “Paranoia” is another example of a Brockington arrangement that does not fit the emotions of her poetry. A flute flutters as she says “lately I’ve noticed nobody talks loud anymore, not even me, I’d really hate to see my family being persecuted for something I haven’t done, eventually you just have to take a stand.”

Me and a Friend is worth a listen if only for its bold closing track, the one moment in her brief career that can be considered supremely timeless – a cinematic masterpiece where Wanda Robinson’s voice is finally matched with ambitious, experimental music that elevates her gritty poetry. “The Un-Hero” is an African American soul poet’s mythic meditation upon war surrounded by an absolutely epic Ennio Morricone style soundtrack. It makes you wish that more of her poems had been complemented by such stunning soundscapes.

Gary Langston’s psychedelic guitar creates a desert, endless and vast, as a background choir wails, Julius Brockington’s cathedral organ soars, Ralph Fisher’s drums thunder, and Jim Wilson’s trumpet blasts, adding to the apocalyptic atmosphere. Wanda Robinson solemnly recites

“A lonely figure moves across the wastelands

Guided by the stench of charred bodies

He carefully steps over the remains of other mothers’ children

The valley is deep with its bleeding grass and aromatic violence

This must be the place

A victim of his own guilt

He walks blindly

It matters not

The dead all look alike

He comes to a rocky pillar

Built in the shape of a primitive altar

He kneels humbly

Heart pounding

Breathing short

He prays to the warlord to forgive him

For being unable to kill”

by Mark Lager

I don’t know where you got your information, but you have been misinformed.

I apologize for not seeing your comment you posted one year ago, I was traveling at the time.

Thank You for bringing this to our attention.

What information needs to be updated?

Where some of this information is derived is from the article “I Usta Be Wanda Robinson” by Sarah Godfrey.

Such a great track and interesting background story, Mark

The folk arrangements and captivating atmosphere actually feels like an instrumental crossover between Fleet Foxes and Love, Wanda’s voice fits very well. I’ll definitely check the other tracks of the album!

Cheers Octavio. She certainly has a strong voice. The arrangements on the other tracks are funk/jazz/soul. Which is why “The Un-Hero” is so unique and unusual.

Beautiful record, and the article comes right in time for the new developments re Malcolm X’s murder.

Cheers C. Wanda Robinson’s poetry still speaks the truth about American politics, race relations, and society 50 years later.

This is really fascinating writing. I have never heard about Wanda Robinson. That song is beautiful, I need to listen whole album.

Thanks for the introduction, Mark. Cheers!

Cheers Mika. “The Un-Hero” is an epic masterpiece. Wanda Robinson’s poetry still speaks the truth about American politics, race relations, and society 50 years later.

You write about obscure albums I’ve never ever heard of. This is a gem, truly beautiful.

Cheers Patrick! Wanda Robinson’s poetry still speaks the truth about American politics, race relations, society 50 years later.

A new discovery for me, that track is awesome. Thank you for the interesting write-up!

Cheers Saliha! Glad you dig “The Un-Hero”! It’s an epic masterpiece!