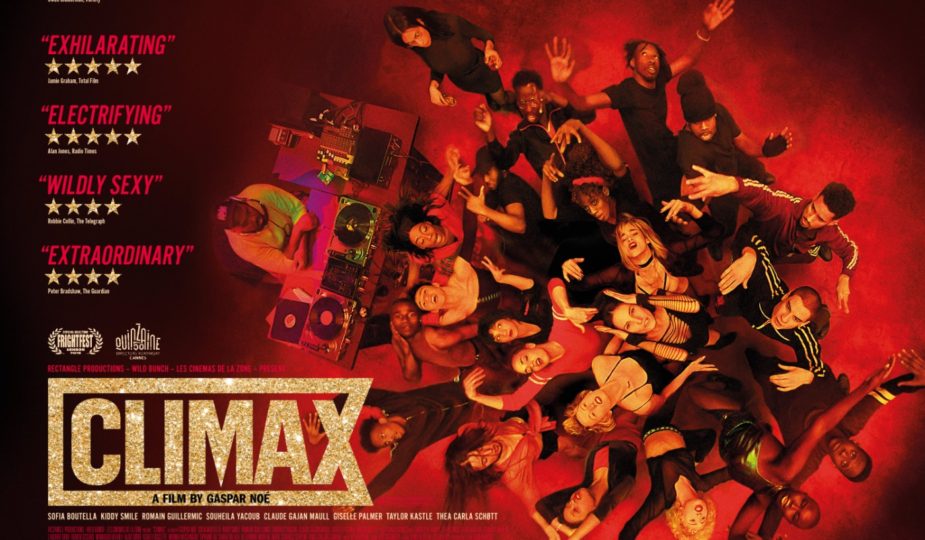

Gaspar Noé’s Climax (2018)

Beautiful depictions of sex and violence, vibrant colours, astonishing soundtracks and uncomfortable steadicam shots are often associated with the films of French-Argentine director Gaspar Noé. Hailed as a unique voice in cinema by some, and perceived as a mere provocateur by others, Noé remains as controversial today as when he exploded onto the seventh art. Through films like I Stand Alone (1998), Irreversible (2002), Enter The Void (2009) and Love (2015); Noé has challenged the limits of the cinematographic form, always focusing on the extremes of violence, often veering into nihilistic territories.

As we are accustomed to in Noé’s cinema, the timeline in this film won’t be a chronological one. The unparalleled Climax (2018) begins with a blood-soaked woman dragging herself across a mysterious white frame, isolated in an endless field of snow. She screams and tries to pull herself forward before collapsing in the snow. The dramatic opening is followed by the credits, allowing audiences to recover their breaths. Noé then introduces his cast: a big group of multi-ethnic and polysexual young dancers. Each one talks about their aspirations, dreams and nightmares. We see them on a TV screen framed by various books and VHS covers that provide clues to Noé’s inspirations: from Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou (1929) to the nightmare of Zulawski’s Possesion(1981); passing through Pasolini’s Salo or the 120 days of Sodom (1975), Lynch’s Eraserhead (1977) or Argento’s Suspiria (1977). A kind of cultural history of literary transgression also appears in the shelves: Kafka’s surrealism, Bakunin’s anarchy and Murnau’s homosexuality; passing through the eroticism of Bataille, Cioran’s nihilism, Nietzsche’s philosophy, Lang’s modernism, etc.

During 1996’s winter, the dance troupe rehearses in the middle of a snowy forest in France. They are putting the finishing touches to a performance before embarking on a national tour to be followed by a series of dates in the USA. In front of a huge glittering French flag, the dancers capture an astonishing, 10-minute uninterrupted high voltage sequence. We watch the troupe perform a kinetic and pulsating pumped-up version of Cerrone’s Supernature, led by choreographer Selva (Sofia Boutella) and overseen by manager Emmanuelle (Claude Gajan Maull). The phenomenal long take is followed by an exquisite 90’s electronica track selection from the party’s house DJ Daddy (Kiddy Smile). The single-take effect continues as the dancers loosen up, chat and relax. Sangria is brought up by Emmanuelle, who has unwisely brought her young son along for the afterparty. What follows is a series of dialogues between the dancers, establishing characters, sexualities and personal anxieties. About 45 minutes into the film, Noé hits us with a lurid storm of opening titles in various stylised club-style fonts: the fun has ended and it’s time to descend into the depths of hell. As the LSD-spiked sangria starts to kick in, the dancers start to act strange. Violence breaks out as they accuse each other of adulterating the drink, and more so as sexual tensions start to arise. The sense of paranoia and claustrophobia mount as Benoît Debie’s camera moves from the ceiling to the floors, getting in touch with the dancers and following them wherever they go.

Through the large halls, the dancers creep over the dark and threateningly monochrome illuminated corridors and cabins. In doing so, they capture almost all the conceivable forms of excess, violence and life-threatening ecstasy. It all leads back to the dance hall, the heart of the celebration. With each return, more and more of the madness is revealed. As the night progresses, the picture, together with the protagonists, continues to lose itself in absolute intoxication, until all humanity and closeness to reality disappears from the canvas. Violence and lust can no longer be distinguished from each other, the dancers melt into indefinable shadows of themselves. During the last minutes, we appreciate the collapse of an inclusive, diverse and independent community.

The depictions of black people as sexual predators and incestuous beasts can be controversial, whereas Noé’s is overall focusing on the absolute degeneration and decline of moral values of the entire multi-ethnic society, not just a few ones. In the end we can see that all the community is coming equally together into the abyss of gloom and intoxication, no one is innocent. To some, Noé might seem to condemn multicultural and liberal societies and sexualities, but I don’t think that’s the point, because there’s a huge French flag in the center of the film’s scenario, the colours represent “liberty, equality and fraternity”. Therefore, we can perceive that he is criticizing the countries that wear the political ideals of “poly-sexual” and “multi-racial”, and we all know that immigrants and members of LGBTQ+ community still continue to suffer from abuses and discrimination around the world. Perhaps, Noé’s films are an acquired taste. He can be hard to take, and sometimes a little extremist and silly. But Noé is an artist with a unique vision, he pulls off conventionalisms with bravura and style. If you think too hard about what “Climax” means, the film starts to deflate. It’s not anything new that civilization is a thin rope, and humanity needs very little excuses to go insane.

by Octavio Carbajal González

If you want to feel miserable and deranged…

Great Review, the movie is an absolute masterpiece. Like the references to Lang, Cioran and Bataille🖤🤘🏻

Thank you Ash,

I wouldn’t say that this one is a masterpiece, it certainly has its controversies and flaws. But, I do think that is one of Noé’s best works.

I also liked Noé’s repertoire of VHS tapes and books. Quite amazing taste!

Enjoyed this piece. Gaspar said that the main theme of Climax was the potential of a group of people to create something beautiful together and then collapse it (Tower of Babel’s concept).

Amazing page !!

Thanks Martin, it absolutely resonates with the concept of the Tower of Babel!

It’s always refreshing to find new, interesting films. This one is new to me and the concept and the structure of film sounds really fascinating. Review is once again wonderfully written. Thanks Octavio. I’ll definitely check this film.

Thanks for the feedback, Mika. I think that you’re also going to enjoy the energetic and propulsive soundtrack of this film. We got Daft Punk, Gary Numan, Aphex Twin, etc. Let me know your thoughts when you finish watching it!

really well written! I wish you could’ve expanded even more of your thoughts on the themes and your feelings when experiencing this gem:)

Thanks for the comment, I think that it wasn’t necessary to expand more. I only decided to focus on the essential topics.

A mind-blowing experience. Selva being possessed with Aphex Twin’s “Windowlicker” is THE scene

I’m glad you mention that scene… it actually resembles the horrific nightmare of Zulawski’s cult film “Possession”

Such a disturbing yet fascinating movie! Total anarchy and collapse but at least the choreography is fantastic!

Oh yes, the choreography is absolutely remarkable, it all came up together in just 2 weeks !

Octavio,

I have to honestly admit I have not been a fan of any of Gaspar Noe’s films, although the hallucinatory, surreal, trippy visuals of Enter the Void burnt out my eyes.

As always, I appreciate your film writing and your cultural references in this review.

Thanks for your comment, Mark. I also think that the cinematography of “Enter the Void” is quite outstanding and surreal, never seen anything like that before.

Sounds like a regular night in Berlin’s Berghain.

Never been there before, I’m actually intrigued about the club’s information !

Disturbing movie. Have you noticed that the Sangria bowl resembles the title cover?

Just realizing it !