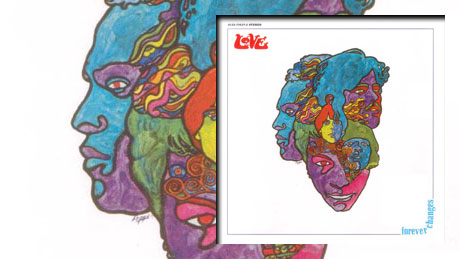

A Beautiful Masterwork of Grim Psychedelia: Love – Forever Changes (1967)

George Harrison was disappointed when he visited San Francisco at the tail end of the Summer of Love. “I went to Haight-Ashbury expecting it to be this brilliant place,” he said in a retrospective interview, “I thought it was gonna be all these groovy… people with little shops making works of art and paintings and carvings, but instead it turned out to be just a lot of bums.” He left California with a sense that the project of the 60s had failed, that the spiritual and artistic hopefulness of the hippie movement, of free-love, and, most especially, the drug culture had curdled into something confused and gloomy. I suspect that when Love’s Forever Changes was released 3 months later, he would have found it a great comfort.

Forever Changes is a masterpiece of 60s psychedelic rock and roll, fusing folk, orchestral, and pop sounds into a cohesive and haunting whole. Though the songs are largely built around lovely interplay between the guitars and an extremely active rhythm section, the band augments traditional rock instrumentation with mariachi horns (“Alone Again Or”), harpsichord (“The Red Telephone”) and classical strings (“Andmoreagain”). The album is a masterclass in tastefully marrying disparate influences. The complexity of the arrangements is extremely enriching, but the additional instrumentation is not a crutch to obscure shoddy or boring songcraft. The songs are recognizable as pop tunes, but they’re frequently discursive, with multiple passages that blend and wind effortlessly within a single track (see the centerpiece “The Red Telephone” or the grand closer “You Set the Scene”). The result is a set of songs that have immediate appeal but also a depth that makes them kind of endlessly re-playable.

Even the catchiest and most straight-forward tracks are compelling and frequently chorus-less, propelled along by very satisfying verse melodies and energetic maximalism in the performances. Listen to the chirping, dueling guitars in the outro of “A House Is Not a Motel” or the enjambed verses and voice-accompanied horn solo in “Maybe the People Would Be the Times…” to hear what I mean. I get the sense that the songs would be somewhat diminished but still quite satisfying without the album’s arrangements, that the recording studio is being used as punctuation rather than instrument.

The lyrics, mostly written by Arthur Lee with contributions by Bryan MacLean, convey confusion, disillusionment, and urgency. From the opener “Alone Again Or”, where MacLean takes a skeptical stance on free-love as freedom, to the closing track “You Set the Scene”, where the only thing Lee is sure of is that “all that lives is gonna die”, Forever Changes creates a patch of darkness within the sunny optimism of flower-power. Violence, grimness, and uncertainty are at the core of Forever Changes: even when it’s imagining a better world, the bad old world is still in view. Lee is surely a part of the counterculture, rejecting the numbing quality of mid-century American life (“The Daily Planet”) and standing in opposition to the Vietnam War (“A House Is Not a Motel”), but he does not seem convinced that everything will come out all right if we only let love in. Opposition remains strong, American life is hard to transform. The outro of “The Red Telephone” is representative: “They’re locking them up today, they’re throwing away the key /

I wonder who it will be tomorrow, you or me.”

These songs, when heard more than half a century later, are as compelling and inviting as ever. The album feels specific to its era but reflects universal concerns. Will we ever stop being disillusioned, let down by the gap between the ideal and the actual? I don’t think so, but luckily, for those times, we have Forever Changes.

by Max Newbie