Türkân Şoray, the Sultan of Cinema – A Worship

Melodramas are the filmic equivalent to country or arabesque music- they have a history of being stubbornly dismissed by the cultural elites who labeled them as sentimental and fatalistic trash for the simple and stupid people, and intolerably inferior to arthouse. This closed-minded understanding of arthouse cinema was temporarily exposed and suspended when Danish director Lars von Trier not only directed the mother of all over-the-top melodramas with Dancer in the Dark (2000), but also set it up as a Musical in which the insufferable Björk took the lead. Under the protective wings of the term ‘Dogma’, suddenly the worst of all telenovela-style melodramas was labeled „arthouse“ and won the Palme D’Or in Cannes.

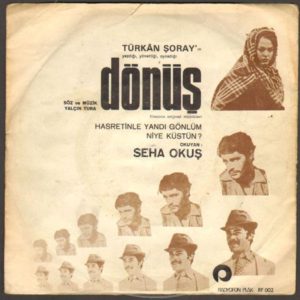

Turkish superstar actress Türkân Şoray never was rewarded such honors, although she took the lead in many truly precious melodramas and even directed some of the best, namely her first one Dönüş (1972), which didn’t won Cannes but the 1973 Moscow Film Festival Grand Jury Prize. But more to that later, let’s first have a look at this woman which cinema historians consider as one of the greatest actresses of all time.

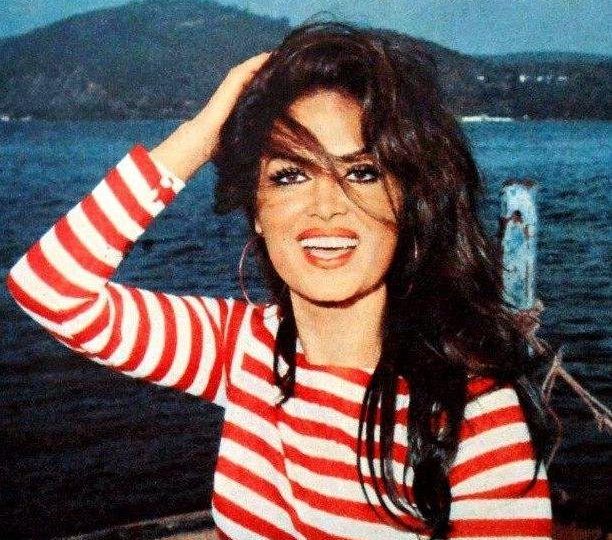

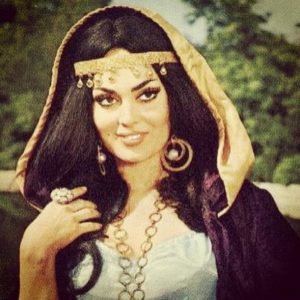

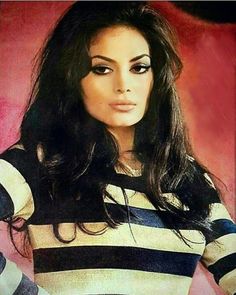

Türkân Şoray has starred in more than 222 films since 1960, inhabiting the record for the most feature films for a female actress worldwide. Scandaliously enough she is not well known outside of Turkey, which  means that billions of men (and women) were robbed of the pleasures of enjoying her divine beauty and sublime screen performances. Often dominating the screen just with the hypnotizing play of her eyes- no matter if she played a rural Anatolian woman with folklore clothes and covered hair or a high-society lady from Istanbul- she was given the highest imperial honors by the Turkish audiences that named her ‘Sultan’. The arab noun meaning “strength”, “authority”, “rulership” encompasses moral weight and couldn’t be more fitting in Şoray’s case: she never reduced herself to her melting beauty but despite built a career on incredibly ‘strong woman’ roles. Cinema has rarely seen a stronger woman, and by that we exclude Western and Asian cinema’s cartoonish angels of revenge that are spiced with incomprehensible psychopathy (Uma Thurman, Meiko Kaji…) The Sultan was different and had it all: playful and feminine and then again hard and persistent in her undeterred pride and strive for justice, Soray oozed moral and aesthetic opulence.

means that billions of men (and women) were robbed of the pleasures of enjoying her divine beauty and sublime screen performances. Often dominating the screen just with the hypnotizing play of her eyes- no matter if she played a rural Anatolian woman with folklore clothes and covered hair or a high-society lady from Istanbul- she was given the highest imperial honors by the Turkish audiences that named her ‘Sultan’. The arab noun meaning “strength”, “authority”, “rulership” encompasses moral weight and couldn’t be more fitting in Şoray’s case: she never reduced herself to her melting beauty but despite built a career on incredibly ‘strong woman’ roles. Cinema has rarely seen a stronger woman, and by that we exclude Western and Asian cinema’s cartoonish angels of revenge that are spiced with incomprehensible psychopathy (Uma Thurman, Meiko Kaji…) The Sultan was different and had it all: playful and feminine and then again hard and persistent in her undeterred pride and strive for justice, Soray oozed moral and aesthetic opulence.

Although the Turks awarded her highest honors and she was the most popular actress of her generation, their ‘culture makers’ at the same time  largely dismissed the highly prolific Turkish mainstream cinema called Yeşilçam (named after the street in Istanbul where the industry concentrated), calling it ‘popcorn cinema for the simple folks’. Maybe besides the usual snobism, this contemptous attitude was also born out of abundance, because Yeşilçam cinema had an output of 300 films each year, with an inflationary amount of ridiculously charismatic actor-types, and the films were often beautifully scored by legends such as Cahit Berkay (Mogollar)– you often don’t realize the specialness of something while it’s happening, but only in retrospect.

largely dismissed the highly prolific Turkish mainstream cinema called Yeşilçam (named after the street in Istanbul where the industry concentrated), calling it ‘popcorn cinema for the simple folks’. Maybe besides the usual snobism, this contemptous attitude was also born out of abundance, because Yeşilçam cinema had an output of 300 films each year, with an inflationary amount of ridiculously charismatic actor-types, and the films were often beautifully scored by legends such as Cahit Berkay (Mogollar)– you often don’t realize the specialness of something while it’s happening, but only in retrospect.

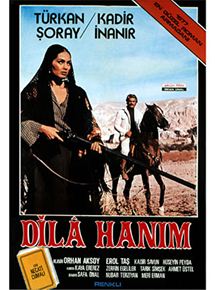

Türkân Şoray did 11 films with another absurdely beautiful and  charismatic creature, Kadir Inanir. The dream couple of the Turkish big screen played in some deeply romantic, yet complex films together, including the classic Selvi Boylum Al Yazmalim (1977) and the mesmerizing, spurred ‘Dila Hanim’, where Türkan is wearing a rifle and galopping on a horse for half of the movie, chasing the killer of her husband in the surreal moonscapes of Cappadocia, and falls in love with him to no happy end.

charismatic creature, Kadir Inanir. The dream couple of the Turkish big screen played in some deeply romantic, yet complex films together, including the classic Selvi Boylum Al Yazmalim (1977) and the mesmerizing, spurred ‘Dila Hanim’, where Türkan is wearing a rifle and galopping on a horse for half of the movie, chasing the killer of her husband in the surreal moonscapes of Cappadocia, and falls in love with him to no happy end.

It is hard to categorize her directorial debut Dönüş (‘The Return’) in a single genre definition. It is a broken love story, social drama, story of a destructive obsession, gender commentary, eerie village horror film, and the first Turkish film picking up the mass-migration of Turkish workers (Gastarbeiter or “guest workers”) to the Federal Republic of Germany, and the tales of the alienation of those workers that became part of the Turkish folklore over time.

In the film’s opening scene we see poor people working on fields, and the feudal landowner and creditor Reşit Bey (Bilal Inci) taking away the land of one farmer due to his unpaid debts. Gülcan (Türkân Şoray) is one of these workers, and she is the only one speaking up against the landlord with her head held high: “Will this little amount of land you’re taking away add more lordness to you? Thanks to you we have understood how small the meaning of the word ‘Lord’ is”. It is the moment the Lord gets obsessed with Gülcan in his own twisted way: he wants to own her at all costs, and he also wants to break her. Less protected because she is an orphan, he orders her to his house in order to ‘work’ there, but Gülcan refuses and tells him that she is about to marry her lover Ibrahim (Kadir Inanir) soon. Being used to get his way, this refusal stings hard and the Lord breaks out in unfiltered, raw emotions: “If I can’t have you then nobody can… I’ll bow your head down, I’ll make you kiss the dust from my boots. I will destroy you.” This is the violent nature of his passion and love, and indeed he turns Gülcan’s life into hell.

one farmer due to his unpaid debts. Gülcan (Türkân Şoray) is one of these workers, and she is the only one speaking up against the landlord with her head held high: “Will this little amount of land you’re taking away add more lordness to you? Thanks to you we have understood how small the meaning of the word ‘Lord’ is”. It is the moment the Lord gets obsessed with Gülcan in his own twisted way: he wants to own her at all costs, and he also wants to break her. Less protected because she is an orphan, he orders her to his house in order to ‘work’ there, but Gülcan refuses and tells him that she is about to marry her lover Ibrahim (Kadir Inanir) soon. Being used to get his way, this refusal stings hard and the Lord breaks out in unfiltered, raw emotions: “If I can’t have you then nobody can… I’ll bow your head down, I’ll make you kiss the dust from my boots. I will destroy you.” This is the violent nature of his passion and love, and indeed he turns Gülcan’s life into hell.

Ashamed, Gülcan doesn’t tell her husband about the events in order to protect and shield their relationship. They have a son together and Ibrahim takes a loan for his first field, the young couple is full of ideals and hope for a better life by cultivating it together, but the furiously heartbroken Lord gives no rest. He plots and destroys and sends out his venal lackeys to pressure Ibrahim with the repayment of his loan and at the same time advertise to him the idea of immigrating to Germany in order to work there and earn the money for his debts and a better future. Desperate and naively unaware of the Lord’s brutal obsession and intruiges, Ibrahim leaves with promises of a quick and wealthy return, leaving his wife heartbroken and unprotected.

The Lord is immediately present to humiliate and terrorize her: “Now you’re without a man. If you need something, don’t hesitate to come to me… I’ll make you go on your knees. I’ll show you whose world this is.” Gülcan’s humble home gets vandalized. Her field and yield gets burned. She’s being left devastated and hungry with a baby, dependant on the alms of the villagers, but still proud and no beggar. She lives for the letters from her husband that regularly arrive once every few weeks and that she has to have read out by an elder man, since she is illiterate like almost everybody in the village. „Read it to me slowly!“ she exitedly admonishes the appointed intruder of private correspondency „I have to memorize it all.“

Ibrahim returns (albeit for a short holiday and not forever as it later gets revealed) and now we see the most interesting scenes in the film. Gülcan sees her husband returning all dressed up, standing in the center of the village with a suit, posh watch and Bavarian hat, like an exotic creature and completely out of synch with his environment, a tourist, an alien. Gülcan’s reaction is an interesting one: she is ashamed and intimidated to look at her transformed husband, reluctantly having a look at him through her hand before her eyes. The story is now one about cultural shock, the clash of civilizations, the encounter with modern life and alienation as inevitable result of it.

For Ibrahim nothing is as it was before: he resents the village life, comparing it to the technologically developed life in Germany. With his many presents to the family colorful and loud consumerism enters the frugal home, and his wife’s reaction to her first encounter with technology such as a taping machine is a long forgotten one: shock and wariness.

In simple yet stunningly effective montages the director Türkân Şoray depicts Ibrahim’s estrangement and change: when he looks at the feet of his wife stuck in dirty galoshes, images of the Western women’s silver high heels flash up in his memory, when his beautiful wife washes him with water that she has heated up on the wood stove, images of hot water running from taps enter his mind. Heartbreaking scenes that somewhat ruin the viewer, since they mark the loss of innocence. Ibrahim is far away with thoughts and leaves again, promising to „Earn more money… more money“ and return soon. Gülcan waits months for his first letter and after that one eventually no letters arrive anymore. The other men in the village are no less useless and ignorant: the obsessed Lord immediately gets on attack mode again, attempting to rape Gülcan, and when fought off and rejected brutally he promises to make Gülcan „the whore of all the villagers“. And indeed soon they withdraw their pittance and outlaw her, and interestingly it is Gülcan’s will to learn to read and her taking lessons from the village teacher that makes her a total leper and now ‘allow’ the other men to harrass her too.

But it were the women in the village who have outlawed Gülcan first and as a result enabled and unleashed their men. Although they may have not had the opportunity to help, they also spared their compassion from her. Gülcan takes the most violent gossip, the most brutal comments and the worst glances from women. women who crush Gülcan as if they were experiencing the hysterical joy of finding someone they could smear. During the deeply unsettling scenes in which Gülcan fights the villagers’ ignorance and hostility, Dönüş leans heavily on the horror-genre, giving the film yet another layer, one that culminates in Gülcan brutally losing her child and the grief of a mother almost going insane and not wanting to bury her dead child, holding the corpse under siege with the help of her rifle pointed at her door to shield off intruders. A haunting scene.

But it were the women in the village who have outlawed Gülcan first and as a result enabled and unleashed their men. Although they may have not had the opportunity to help, they also spared their compassion from her. Gülcan takes the most violent gossip, the most brutal comments and the worst glances from women. women who crush Gülcan as if they were experiencing the hysterical joy of finding someone they could smear. During the deeply unsettling scenes in which Gülcan fights the villagers’ ignorance and hostility, Dönüş leans heavily on the horror-genre, giving the film yet another layer, one that culminates in Gülcan brutally losing her child and the grief of a mother almost going insane and not wanting to bury her dead child, holding the corpse under siege with the help of her rifle pointed at her door to shield off intruders. A haunting scene.

The never-ending crescendo of gruesome events which cannot all be revealed here causes the final return of Gülcan’s husband Ibrahim. Only he is not her husband anymore. Alarmed by a letter he drives to Turkey with his new German wife and their mutual baby, a truth that is revealed to Gülcan when she discovers their bodies after they had a deadly accident. Türkân Şoray makes subtle commentaries in scenes like the one where Ibrahim races his car in terror and his blonde, posh wife turns on the radio for some music, oblivious to the situation with its fatalities- these are two worlds and mentalities which are too far apart, with the differences stabbing reality mercilessly in such moments, leaving it broken.

Dönüş has no happy end to offer, but gives a lesson on compassion in its final scene which provides a gentle relief to the sounds of Seha Okus’ beautiful song “Hasretinle Yandi Gönlüm“ („My Heart Burned With Longing“). An exhausted Gülcan takes the surviving child of her estranged husband and walks away with it, leaving the ignorant village behind in an act of grace. No matter what happened and how much she has lost, this is still a strong and unbroken woman, one where the word ‘victim’ doesn’t cross your mind, but instead a thousand other nuanced thoughts and sentiments. She learned to read and makes her way. She was poor but kept her dignity. She didn’t bow down to the obsessed Lord, but killed him just when he thought that he broke her down and owned her. She is of the solid material to carry her story into her country’s folklore and turn it into an immortal elegy.

has no happy end to offer, but gives a lesson on compassion in its final scene which provides a gentle relief to the sounds of Seha Okus’ beautiful song “Hasretinle Yandi Gönlüm“ („My Heart Burned With Longing“). An exhausted Gülcan takes the surviving child of her estranged husband and walks away with it, leaving the ignorant village behind in an act of grace. No matter what happened and how much she has lost, this is still a strong and unbroken woman, one where the word ‘victim’ doesn’t cross your mind, but instead a thousand other nuanced thoughts and sentiments. She learned to read and makes her way. She was poor but kept her dignity. She didn’t bow down to the obsessed Lord, but killed him just when he thought that he broke her down and owned her. She is of the solid material to carry her story into her country’s folklore and turn it into an immortal elegy.

Dönüş is a remarkable achievement of not only the actor but also writer and director Türkân Şoray, who demonstrates once again how to combine true beauty, strength and overflowing talent- more woman is not possible.

by Saliha Enzenauer

Ich liebe deine Exkursionen in die türkische Film- und Musikwelt…so wundervoll und voller Leidenschaft geschrieben!

Saliha,

This has been my favorite of your series of articles on Turkish movies and music. Türkân Şoray is such a beautiful, complex actress and your detailed descriptions of the film she directed (Dönüş) makes we want to see it. It sounds deeply haunting and incredible. (I would also like to see the other film you mentioned featuring the “surreal moonscapes of Cappadocia”.) Thank You for introducing me to Türkân Şoray and sharing her story with us.

Hi Mark, thanks, she’s fascinating. Cappadocia is totally your thing, I’ll tell you that. Surreal haunting landscapes.

Love this column and wished that you would cover more countries, although I have the feeling that turkish culture is somewhat special. There’s so much that we don’t know, so many scenes, styles, artists… Thanks for writing about exotic things, that’s really valuable.

Thanks, I’d love to have more experts from other countries on here… working on it.

Türkan gibisi yok!

Fuck she is beautiful

Türkân Şoray Kadir Inanir Atif Yilmaz Cahit Berkay = KALITE!

Hi Saliha,

Beautiful introduction and marvelous review- invaluable gift for Türkan Şoray and her culture.

I´m truly amazed with her prolific career, she isn´t just a pretty face. Based on your words, I can immediately notice that Türkan has strong and passionate ideals about the role of women throughout history.

The movie looks painfully devastating, but I must see it as soon as possible, you got me interested.

You know that I love this specific kind of social-realist cinema… Gülcan stands for women in the migrant families which are victimized both by her husbands and by the residents in her village.

I bet that no one else in the world is paying this amazing tribute to Turkish Culture, you must feel very proud. Thank you for this article, there´s always an unparalleled passion inside your words.

Thank you so much for your lovely words, Octavio. This is a topic close to my heart and I enjoy revisiting these films and artist, it’s like a time travel to my childhood and youth. Just by her looks and talent, Türkan is somebody legendary who should be more known, but we live in a eurocentric world. I wanted to introduce her anyway…

She’s beautiful and I’m sincerely shocked that I have never seen this woman before, because I consider myself a big cineast. But let’s talk about your writing: brilliant opening paragraph where all cultural certainties get deconstructed. Read the opening paragraph and you gotta pay respect to the rest. I know nobody that can do that the way you do, its an amazing talent. The rest of the article is wonderful as well, deep insights and you guard the reader so well along the plot of this movie. Now I’m excited to watch it, hope I can automatically generate subtitles. Thank you for the very pleasant read and for introducing this obviously fascinating woman to me!

Such things as the comparison to von Trier’s just have to be said and exposed. Thank you so much for your lovely & encouraging words.

Sultan ❤️❤️❤️

Thank you for your beautiful description of this amazing actor and director. After watching Dönüş and seeing the Sultan’s talent and beauty ignite the screen it’s difficult to Imagine a film or story with more passion, strength and (despite the tragedy) the hope that we are show in this film. It’s a rare and beautiful film and performance. It’s incredible to learn from your article the volume of films that were made.

Criminally beautiful. I can understand that landlord!!

She is very beautiful and your writing is just sublime. I love everything about this post!

I just fell in love with her.