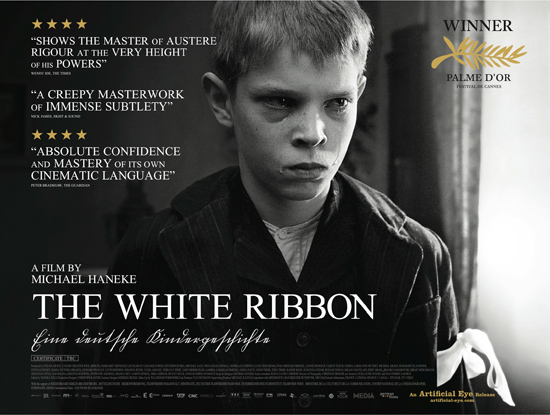

The White Ribbon (2009)

Director: Michael Haneke

Born in Munich in 1942, Austrian director Michael Haneke has consolidated in recent times as one of the greatest exponents of European cinema. Renowned for his gloomy and disturbing style, Haneke delves into the dark human nature and the discomfort that it produces, and he often takes violence as a starting point. Haneke has acclaimed films in his repertoire, such as “Funny Games”(1997), “La Pianiste” (2001), or “Amour” (2012), which are essential to understand the keys and the development of his style. The vast majority agrees that The White Ribbon (‘Das Weisse Band’) is his definitive film. A rather unknown but true masterpiece of contemporary cinema.

Filmed in beautiful black and white, The White Ribbon is narrated entirely by the unnamed teacher (Christian Friedel) of a small German village in a time set just before the First World War. The opening scene shows the village doctor (Rainer Bock) suffering an accident on his horse, when he races into a rope that strangers stretched around two trees close to his house. There is neither an explanation nor a suspect for this event, that inaugurates a spiral of unbridled violence, which includes abuse towards women and children, animal abuse, and the unfolding of guilt and shame, with the incessant reminder of a white ribbon as a symbol of innocence and purity.

The baron (Ulrich Tukur) acts as a feudal lord with his employees, and begins to exercise brutal domestic violence against his wife (Ursina Laudi), who tolerates his humiliations. Similar stories of marital ruptures and verbal / sexual abuse of minors, are just some of the atrocities that begin to happen in several homes of the town, and each story is described with chilling coldness and brutal despair.

The whole set develops a micro universe that gives a preview of the German society that would come to reality 20 years later- when the children of the town reach maturity, they will transform their harsh reality into something tremendously sinister. Haneke does a profound and detailed research on the roots of a certain type of evil. Hypocrisy and irrelevance begin to grow inside the town, and the disaster begins to unfold.

Deliberately, the film invites viewers into every corner of the town, from its huge mansion to its humblest home, finding in each one an air of restlessness and bewilderment. The “perfection” of the houses and the cordiality that the villagers display to the outside only hides the overwhelming darkness being lived inside. The behavior of the children participating in the film is fiercely analyzed and thoroughly absorbed. They are tremendously subdued small human beings, brutally indoctrinated by their elders. But they are also not innocent- they do as they see and are being told.

Although the film has been interpreted as a representation of the origins of German fascism, Haneke is actually showing us the brutal consequences of abuse and authoritarianism in general, as well as the religious – specifically evangelical- intolerance and indoctrination that always existed. While The White Ribbon provides no final or easy answers, the film gives us a sublime and lucid experience in which one fundamental answer is raised to many of the problems and crimes that have been destroying our society since the last century. We are still immersed in a society unable to debate and find strong solutions, a society that is surprised and indignated of the atrocities that are committed everyday in the world. These events are the result and the consequences of the seed that has been sown. Haneke seems to argue that, until another great confrontation of nations happens, we will not realize the seriousness of the situation, that we are inside a pot that is about to explode.

The White Ribbon is a gigantic artistic reflection that robs us from the false belief that we didn’t see it coming, that we don’t know the cause of evil. We are reluctant to look inwards, and the comfort of looking away prevents us from changing things,which leads to irremediable consequences.

by Octavio Carbajal Gonzalez

Absolutely wonderful! Your reviews are always so well written and thoughtful.

Great read,after reading this review I’m going to watch the film..

Brilliant review! This is without doubt one of most disturbing movies I’ve seen. The remote village setting and filming in black and white only add to two and a half hours of dread filled viewing. Thanks for reminding me just what a brilliant but disquieting piece of moviemaking this is!

Thank you very much, Serge. I highly appreciate that you took the time to read my review, it’s not easy to watch because of it’s disturbing and dreadful themes, but there’s something that keeps you sticked and intrigued throughout the whole movie, massive experience..

This is pure quality, Octavio. The review is great and very reflexive, haven´t seen this movie . Thank you !!.

Thank you so much, Martin. So happy to see the response of people, and I´m so glad that Vinyl Writers has a special place for this type of movies. For me, this is Michael Haneke´s masterpiece. It won´t be easy to watch, but I assure you that this one is highly rewarding at the end.

This became my favorite film site. Exquisite reviews and selection of film. White Ribbon is an instant classic.

Great film and wonderful review. I was first impressed with his original ‘Funny Games’ back then and Haneke just kept evolving and finding his very own cinematic language since then. I barely could watch White Ribbon because of the cruel manners of the people – old-fashioned in the most negative sense. Haneke manages to gives this a mystery vibe whilst staying realistic.

The most unforgettable scene for me is the end, where the village gathers in church after the war breaks out. The people seem excited, not worried. “Now everything would change and be better”. War as chance, as outlet for the evil tension that built up and and the moralic ‘no way out’ that the people have manouvred themselves in. It is more than plausible to me. Brilliant

That makes me feel great, thank you Daiki for appreciating the selections and the reviews, that was the idea from the beginning, and one of the main reasons that I decided to join Vinyl Writers: to dig inside movies that will never die, and that somehow makes us feel connected with reality, movies that show us the philosophy, the joy and also the awfulness of life. This one left me highly uncomfortable, but after I processed and analyzed it, everything made sense. A 10/10 movie. The final scene that Saliha mentions, is one of the most disturbing and shocking I´ve ever seen, it seems that everyone inside the village finally accepted the birth of evil.