The Measure of a Man (2015)

Film titles which take on a different meaning in the course of their translation are an interesting and frequent phenomenon. Lost in translation, a classic such as The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly becomes “Two glorious scoundrels“ in German, Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now reads as “When the gondolas are in mourning“ and Melville’s Le Samouraï becomes „The ice-cold Angel“. While these translations are often perceived as annoying nonsense with a hilariously open distrust in the quality of the film’s original title, they often represent a culturally marked interpretive emphasis, a certain point of view on the story and characters that can enrich the film. Such is the case with Stéphane Brizé’s La loi du marché, where the literal translation “The law of the market“ had to make place for a more personalized perspective emphasizing the basic humanity expressed through its English title The Measure of a Man. In this case, both titles complement each other and become indispensable, as the inhumane laws of an opaque market determine the value of a human in our times.

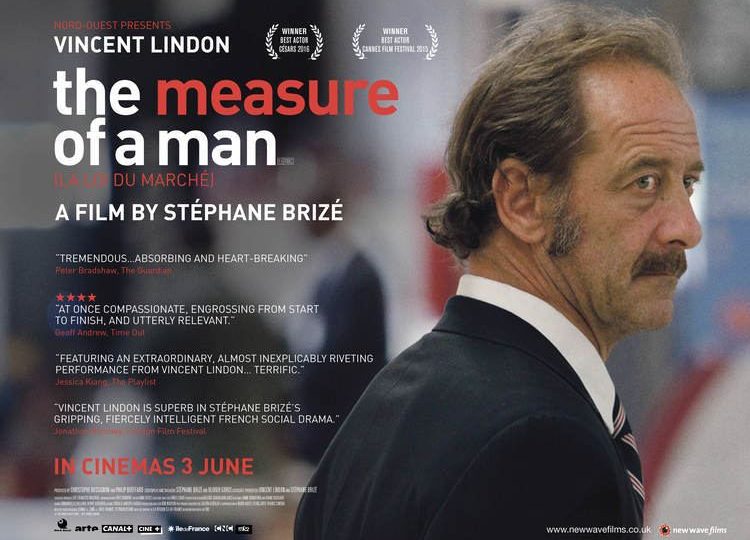

The Measure of a Man by French auteur Stéphane Brizé is great social realism and bears many similarities with Ken Loach‘s 2016 Cannes winner I, Daniel Blake, but Brizé’s film was realized one year earlier, and is a more holistic experience in my opinion. Vincent Lindon, brilliant and understated as always, plays the middle-aged Thierry who gets laid off from his skilled factory job. The husband and father to a physically disabled son with college ambitions subsequently goes through the absurdities and humiliations of the depersonalized unemployment industry. As is so often the case, his unemployment turns into a bureaucratic full-time occupation, filled with senseless workshops and retraining programs in which the participants’ existence and personalities are under the looking glass and evaluated in a degrading way. Thierry tries to stay afloat with credits and by selling the symbols of his former middle class status like his holiday camper, but the downward spiral is looming: the descent into poverty is only one unforeseen expense like a car repair bill away, reflecting the reality of more than half of the citizens of America and rich European countries.

Thierry eventually finds a job as a security man in a Walmart-like mega market, and this is where the film takes a different turn than Daniel Blake and becomes a portrayal of the corrosive banality and cruelty of modern employment. Placed into the security industry, one of the few growing branches in modern societies obsessed with security and health, Thierry is often controlling the giant All-seeing eye CCTV surveillance system in the supermarket, forced to monitor customers and workers for potential theft. He is drawn between his duty and his loyalty to those he is forced to spy and suspect on, since they often are companions in living in precarious circumstances. There is the old, humble man stealing food that he wants to pay for, but it’s just in two weeks that he will get his pittance from the state. There is the low wage cashier who pockets a few discount stamps and is fired for it. Another cashier books the bonus points of non-participating customers on her own card, and she is fired and kills herself in despair. Goddamn, you think, why are these lives being ruined for such minor offenses and violations of rules that make no sense anyway outside of chicane and inhumanity? And where are the CCTV’s and harsh punishments in the Wall Streets, tax havens, parliaments and war ministries of society? The peasantry and humiliation of the contemporary working underclass is absolute.

The bleak surveillance camera shots in the film are not only a reminder of our overall surveillance, but the many ankles and perspectives of supermarket shelves with endless product variations also demonstrate the reason for the deep dysfunction of modern life: our societies have arrived at the gates of misery for plastic-packaged trash that we do not need, for artificial, consumerist ways of life imposed on us for endless growth and profits. The realization of the sheer magnitude of our humiliation is devastating. At one point, Thierry cannot take it anymore and walks away from his job.

Is this open end a reason for hope? Maybe we get back at Ken Loach to answer that question. The greatest living British filmmaker (aged 85) continues to fight for the oppressed and dispossessed through political grandstanding and films such as his latest, Sorry, We Missed You (2019), which deals with the decline of a working class family struggling to meet the exploitative demands of the new gig industry and dealing with the indignities of being a self-employed Amazon delivery driver. Hard to think of anybody else that embodies true Labour values like the fight for the working class more than the principled socialist Loach. Yet, the Labour Party under class and race supremacist Keir Starmer abandoned that fight and expelled Loach “for supporting expelled members” (sic!) like Jeremy Corbyn, the victim of a paralyzing witch hunt which continues and now threatens to expel hundreds of Jewish Labour Party members. Simultaneously, Starmer invited islamophobic, racist donors like David Abrahams back to Labour, all in total absence of a social agenda or even the pretense of having one.

Again, this is not fake news: Ken Loach has been expelled from the Labour Party. There can be no hope.

by Saliha Enzenauer