Le Samourai (1967)

There is no greater solitude than that of the samurai unless perhaps that of the tiger in the jungle.

Book of Bushido

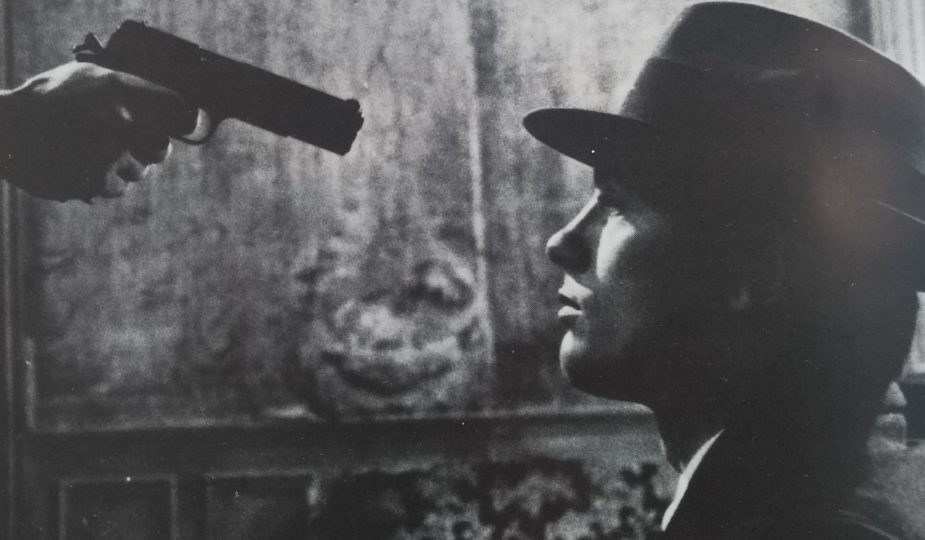

Something is wrong with Jef Costello (Jean-Pierre Melville opens his masterpiece from 1967 with the fictive quotation from above, allocating it to the ‘Book of Bushido’. It is laid upon the first image of his masterly painted grey cinematography with sparse strokes of blue and green monochrome: Costello is smoking in his bed, almost completely merging with his room that with its moss green walls indeed reminds you of a jungle. He is barely visible- it is only the smoke that hints at him. This opening scene’s long shot has a slight vertigo effect that is not due to some shaking of the cameraman’s hands, but tells us that something is not quite right.

In the next setting Costello is shown through the rainy windows of the car that he is stealing. He looks straight ahead, not even looking away as he selects between numerous keys on the passenger seat to start the car. Costello looks at the world as through a veil, ignoring the flirty smile of a by-driving beauty as well. This beautiful killer is not emotional or hedonistic, but disciplined, strict and seemingly asexual. There is no hint of any tension or panic, no cold sweat, and as the film moves on, the inner world of Costello can only be guessed by the reactions and mirroring of the

people who encounter him on his way.

It’s these little hints that tell us that Le Samourai is not only a cool neo-noir thriller, a masterpiece between Nouvelle Vague and Film noir, but Melville’s Costello suffers from schizoid personality disorders. The director dealt extensively with the disorder in the preparation of Le Samourai and cast the perfect actor for its portrayal without psychologizing.

Alain Delon. Does he have a pulse? An ice-cold destructive angel who often seems to be in a dreamlike, somnambule state that makes his beauty blur, making it tolerable. Gracing the screen with glacious eyes and seemingly untouched by it all, but moved by an anonymous compassion. Delon achieves maximum effect with minimal theatrics and dialogue. Singularly handsome and disarmingly serious, Delon agreed for his first project with Melville after the director read the screenplay to him, left intrigued by the fact that there was no dialogue within the first 10 minutes.

On the surface a thriller, ‘Le Samourai’ is not borne by the usual effects, but by a strict code of conduct, an elegant and cool masterpiece. Delon’s congenial performance takes the suspense out of almost anything in this movie, in the true sense of epic drama that is not about the whodunnit or effects, but provides an introspective layer for a deeper understanding. In this case this layer is the cold shiver on your spine, constantly just a few degrees below your feel-good temperature. And this subtle shiver reverberates long after Costello says goodbye to life and the screen with a stoic look. No catharsis here.

‘Le Samourai‘ also marks the peak of the holy trinity of French cinema: Jean Pierre Melville, Alain Delon, and Francois de Roubaix with his congenial score and electronic theme. Roubaix was a brilliant autodidact and electronic innovator to whom many French artists like Daft Punk or Air refer to as huge inspiration. He died way too young with 36, condemned to be a briefly shining meteor in music history, while his themes and scores for films such as ‘Le Samourai’, ‘Commisaire Moulin’, and ‘Dernier Domicile Connu‘ remain appealing to this day and are well worth exploring.

[…] and white crime and noir films or Sergio Leone Westerns in sepia. One day it was a film called Le Samouraï that we watched. The film was an anomaly even within the most exquisite selections of the genre. […]

[…] Nicolas Roeg’s Don’t Look Now reads as “When the gondolas are in mourning“ and Melville’s Le Samouraï becomes „The ice-cold Angel“. While these translations are often perceived as annoying nonsense […]

[…] focused and chilling performance as ice-cold and detached killer in ‘Le Samourai’ (read my review here), the most acknowledged film in Melville’s oeuvre. With no visible feelings and thoughts, but […]