The Many Art’s of Jazz. Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section

by Charles Pearlman

It’s unfortunate that many of the most brilliant minds often self sabotage and can be their own worst enemy. Rarely does the genius appropriately manage their intellect, creativity, zeal, or any of the qualities that lead them to fame and wealth to begin with. Art Pepper is one of those tortured geniuses. He defines the noun “natural”. From his first days playing clarinet it was clear he had a gift. As an adult he rarely to never practiced, but always had his chops. Whether he was locked up in jail, or months into a vicious heroin bender, he could pick up his horn and sound like he never set it down. Despite his god given talents, he struggled with demons his entire life. Though he was often his worst enemy, his struggles were not always self inflicted, and began before he left the womb.

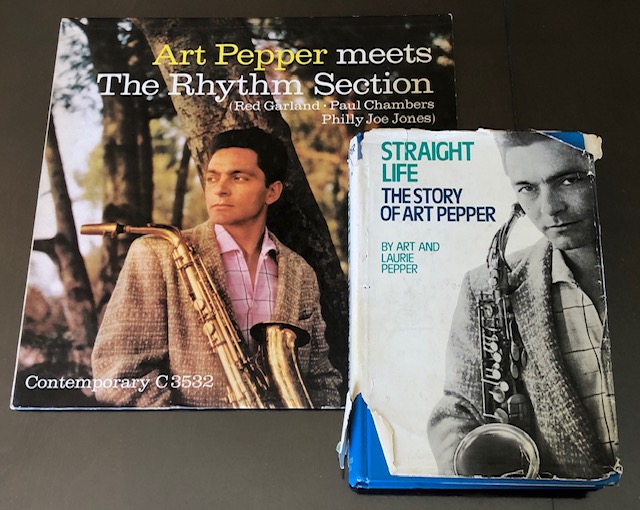

I recently read “Straight Life: The Story of Art Pepper“, authored by Art and Laurie Pepper, his third wife. I’m sure I can speak for anyone else that’s ever read this when I say we’ll never look at Art Pepper the same again. To say he lived a lifetime of hardship is the understatement of the century. He was a peeping Tom, addicted to sex and drugs, a WWII veteran, spent several years in jail, and had one of the only occupations where white people in the 1950-60’s might endure prejudice, a jazz musician.

Mildred Bartold, Art’s mother, became pregnant with Art when she was just 15. She had met his father Arthur Edward Pepper earlier that year, and soon after was pregnant. His father was older and already had plenty of life experience. He had been around the world on oil tankers and freight ships, and was in favor of having a child. His mother was just a child herself and was terrified of the idea. She starved, drank copious amounts of alcohol, and did anything she could to miscarry. Despite all her attempts, she was unable to kill the baby growing inside her. Her inability to miscarry was her greatest gift to the world, and Art Pepper was born September 1, 1925.

Due to her abuse of herself and the fetus, Art was born with rickets and jaundice. The doctors were certain he would die. According to the second wife of Art Sr., his hands and feet were deformed and looked like the beak of a bird. Art’s mother was unable to produce milk, and the doctors gave him a formula for barley gruel, which had to be cooked all day for his body to accept it. They advised his parents to not bathe him in water, but to rub olive oil on his skin instead. Miraculously at age 2, he grew healthy and survived. Those deformed hands would grow vital and dexterous, and soon the whole world would know the skills they possessed.

This wasn’t the end of his childhood struggles. Art Sr. would still go to sea to make money for the family. Once he came home unbeknownst to find Jr. on the porch- locked out of the house, freezing cold and hungry. His mother wasn’t home, and he had to break the front door down to give shelter to their child. Art Sr. never forgave his wife for trying to kill their baby and he was frequently violent. Art suffered through all of this, and the psychological effects were noticed immediately.

As a young child, Art was terrified of everything. Clouds scared him. In his words, “It was if they were living things that were going to harm me.” His parents fought constantly. Art would hide under the sink and listen to his father beating his mother. He broke her nose several times, and Art would clean up the blood himself. His parents eventually separated, and at the age of five he was sent to live with his grandmother. She was a harsh woman, who Art Sr. never got along with either. She would constantly scold Art, he received no warmth or affection from her. “I was terrified and completely alone. And at that time I realized that no one wanted me. There was no love and I wished I could die.”

Life would improve for Art when at age nine his father bought him a clarinet. Art took lessons from Leroy Perry, an older man who treated him with love. He showed promise immediately- though he rarely practiced, his amazing skills were visible from the very beginning. His teacher told him that if he kept playing his horn, he would be famous from coast to coast.

Art began his professional career playing in the Los Angeles area in the early 1940’s. He played alongside Dexter Gordon, Charlie Mingus and others. According to him, there was very little racism taking place, no violence, and far less hard drug use than in the 50s. He was having a ball, enjoying his youth, good looks, and incredible musical talents. He was 17 years old and had just recently married his first wife Patti. Life had finally dealt Art a good hand. Sadly when things were just getting on track, he was drafted into the army and sent overseas during WWII.

Skipping ahead several years, Art returns back to home and begins playing professionally. He joins Stan Kenton’s Big Band, which by all accounts sounds like a blast! He made many friendships that would last years to come, and Stan was like a father to everyone. This is also where he met his best and worst friend that would last the rest of his life: heroin.

In 1950 Art was in Chicago. He was depressed about being away from Patti for so long and cheated on her. This brought him great shame and loneliness, he was in a dark place, haunted by his inner demons. Staying at the Croyden Hotel, he returned to his room to find three band mates. They were snorting heroin. Knowing his addictive personality, this was something he knew he shouldn’t try. But being in such a state of despair, he took his first taste against his better judgement. This experience began what would cycle into a vicious addiction. He recalls this night in his own words, “all of a sudden, the demons and the devils and the wandering and wondering and all the frustrations just vanished and they didn’t exist at all anymore because I’d finally found peace.” The woman who served him his first dose told him to look at himself in the mirror. “I looked in the mirror and I looked like an angel. I looked at my pupils and they were pinpoints; they were tiny little dots. It was like looking into a whole universe of joy and happiness and contentment.”

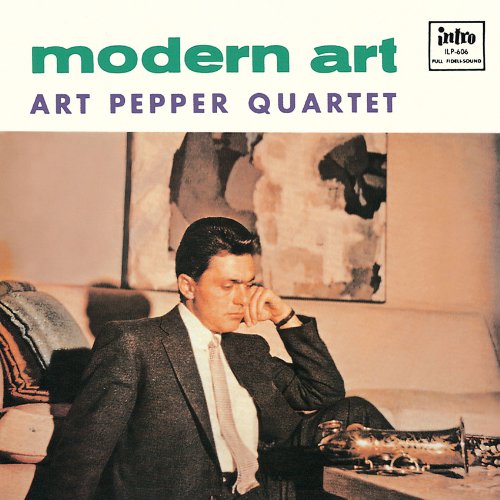

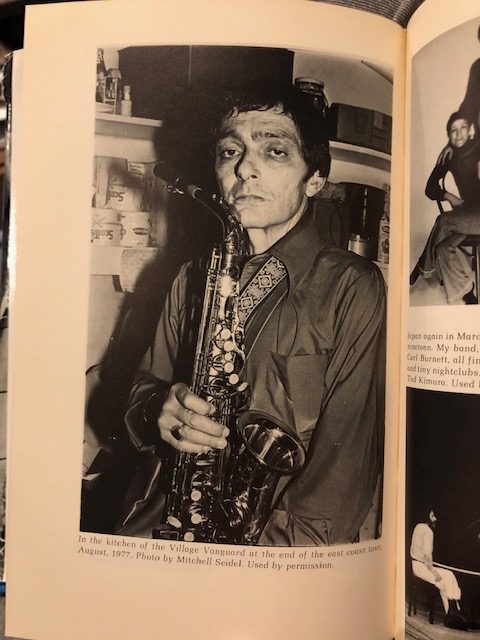

Seven years later, Art is 31 years old and deeply addicted to heroin. He’s now been an intravenous user for years, and before reading his book, I had always thought his addiction came later in life. The pictures of him in the 1970’s show a face sunken and sullen from years of hard drug abuse, but the pictures in the 1950’s show a handsome man I probably wouldn’t leave my girlfriend alone with for long. Handsome and stylish, and showing no signs of someone struggling with a ferocious addiction. Sadly this was anything but true.

On January 19th 1957, Art’s second wife Diane wakes him and says, “You have a recording date today.” He hadn’t played his horn once in months. In fact, he hadn’t done anything in six months other than shooting heroin and laying in bed. Diane had gone to Les Koenig of Contemporary Records and booked Art the gig, in an effort to get him out of the house, make him play his horn, and save his life. Art responds, “Are you kidding? With who? And where? And what?” This was no ordinary date. The band consisted of the greatest rhythm section in the world, 3/5ths of the Miles Davis Quintet. Red Garland, who’s delicate keys earned him a spot in the hippest band playing. Paul Chambers, who’s fast fingers and skills with a bow left every other jazz bassist in the dust. Philly Joe Jones, enough said.

Art was furious. The only words he had for his wife were obscenities. He recalls the story of that day. “I got my horn out of the closet, got the case and put it on the bed and looked at it, and it looked like some stranger. It looked like something from another life. I took the horn out of the case. When you take the saxophone apart there’s the body piece, the neck, and the mouthpiece, and those three pieces are supposed to be wiped and wrapped separately when they’re put in the case. Evidently, the last time I’d played I’d been loaded and I’d left the mouthpiece on the neck. I had to clean the horn because it was all dirty. I had to oil it and make sure it was operating correctly. On the end of the neck is a cork, and the mouthpiece slips over that. I had to put a little cork grease on it. I grabbed the mouthpiece and pulled. It was stuck at first and then all of a sudden it came off in my hand. The mouthpiece had stuck inside it, and on the end of the neck was just bare metal. It takes a good repair man four or five hours to put a new cork on. It has to set. It has to dry. It has to be sanded down. I didn’t have time for that. I was going to have to play on a messed up horn.”

And thus, the stage has been set for Art Pepper’s magnum opus, “Art Pepper Meets the Rhythm Section“. This is without a doubt my favorite album of his, the 10th as a band leader.

Art taped the mouthpiece back on the horn, doing the best he could in the situation. He had no idea what he was going to play. He had never played with any of these cats before, and they play together every night.

Les Koenig had always been an admirer and friend of Art Pepper. Diane drives them to Melrose Place, the site of the recording studio. Les greets him with a grin, but knew full well he’s struggling with addiction. He tells Art, “It’ll be alright. Everything’ll be alright.”

It’s during this session that Art shows the world what a “natural” is capable of. Though he hadn’t played one time in six months, took the needle out of his arm an hour earlier, and using a busted alto, he records the best album of his career. From the very first tune “You’d Be So Nice To Come Home To“, his broken mouthpiece is no match for his gorgeous tone. Art has a distinctive tone which is immediately noticed as his own. He blows sweet and lovely, beautiful notes of a maestro flow from his horn. Paul Chambers has a wonderful bass solo and hands the lead back to Art who simply can’t play a bad note. This was the first song recorded that day, and even he knew he sounded wonderful. That took the edge off, and relaxed the young saxophonist. Here he was, playing for the first time in months, holding his own with the world’s greatest rhythm section.

“Imagination” is a bluesy ballad which shows a more affectionate side of Art. His horn tells a story of beauty and love, such grace to the flow of his notes. Again, he easily overcomes his poor health and broken sax, and blows as if he’s been exclusively practicing this song for weeks.

“Straight Life“, which his life is anything but, became the title of his autobiography that I’ve quoted. A cooker which showcases Art’s fast fingers. He rips the alto top to bottom and everywhere in between. The fact that this is his first time blowing in months is like defying the laws of physics. It’s almost impossible to comprehend how he stepped into the studio and moved his fingers with such dexterity, and that tone! Pure Art Pepper, nobody else, unquestionably. Paul Chambers uses the bow, and the rhythm section is in tight continuity. This concludes side 1. There is certainly no evidence of foul play. Nobody would dare assume the last 6 months of Art’s life would be what it truly was.

The Dizzy Gillespie composition (credited to Chano Pozo) “Tin Tin Deo“ has an exotic rhythm, of course no challenge for this section. Beginning with rimshots drums, and cymbals, Art joins in and blows with all the expression in his soul. He’s simply marvelous, his tone goes from a low whisper at times to soaring high. Beautiful vibrato, his flow is sublime. My personal favorite tune on the album, highlighted by this marvelous rhythm section. Red Garland is superb, but Philly Joe owns this tune. Holding down a rhythm the entire way that only masters can hold for a single staff. His solo is outstanding, never imitating his last move, constantly changing, simply brilliant. Art comes back playing the chorus so beautifully, a true masterpiece.

The album concludes with “Birks’ Works“. Art blows like a champion. That infections tone cannot be faulted no matter the obstacles. He sounds so cool, like a hip cat strolling the alleyway, knowing damn well what they got is hot. The band backs him up perfectly as expected. Garland has a great stride to his solo. Paul Chambers diligent fingers play wonderfully, and Philly Joe accompanies perfectly. This fabulous tune concludes the album we don’t want to end.

This album, rightfully so, was met with rave reviews. Downbeat magazine gave it 5 stars. 62 years later this is still a masterpiece, and I’m quite certain people will feel the same for another 62 to come. After the recording was finished, Diane looked at Art and asked if he would forgive her. He was so relieved it was over and said, “Everything’s cool.”

Art Pepper would continue to struggle the rest of his life. He spent years in jail, and decades addicted to heroine. He tried to clean up on several occasions, but was never able to fully kick his addiction. In April of 1978 he checked into rehab, not for the first time. The head psychiatrist asked him what month it was. He answered March. It was June. He couldn’t remember who the President of the United States was. There are a hundred other struggles, idiosyncrasies, and insanity’s I haven’t mentioned.

Art Pepper never lived the Straight Life. He was unfortunately one of the many tortured musical geniuses that turned to the needle and spoon to conquer their inner demons, and instead cultivated one they could never defeat. Heroin is the two headed monster of the music world. While many of the greatest musicians of the 20th century made their best music under its influence, they were also slaves to addiction in their private lives. There is no question that heroin was one of their most significant influences and a catalyst in the creation of their art. However all of the great musicians addicted to heroin, Charlie Parker, Billie Holiday, Keith Richards, Lou Reed, Chet Baker, Kurt Cobain, Art Pepper, and countless others share a common thread other than addiction. They were geniuses long before they were addicts. And though they lived life through the lens a narcotic fog, they were able to create some of the finest music the world has ever known, and their sacrifice will be cherished for generations more to come.

by Charles Pearlman

Great article he really was a natural. I’m a Jazz-collector myself and would like to pitch you a few stories that I wrote. How can I do that?

Wonderful write-up.

Great article! Ordering the book now!

Didn’t know about all of this, but I sure love this album. Intruiging story!

The last paragraph is pretty contradictory. The article has tons of support of Heroin being destructive, but little for it being a creative catalyst. This myth Has always surrounded drugs, mental health and creativity. At least the author gets it partly right, “They were genius long before they were addicts.”

Good read. An additional focus on Art Pepper’s racist tendencies, especially after imprisonment, would have been more balanced. After prison he deliberately formed an all-white quartet as one example.

Yes but I’d hardly label him racist, simply because he lead an all white quartet. It’s awfully difficult to be prejudice against blacks and love jazz music. He, and anyone, realize it’s a Black American invention. He endured prejudice from the black community at times, so called friends, but that hardly made him racist in return. This might be part of the reason he played with fewer blacks himself, yet he continued to play with whites, blacks, and Asians until the end of his career.

I hate our overly sensitive times. Literally everything is racism or incorrect. Now Art Pepper is a racist. Did Pepper discriminate, belittle or enslave minorities and made their lifes worse? I don’t think so! So he did play with an all-white band. The Beatles are all white. The Stones. Literally all blues based bands. And there are all-black bands as well!! All racist? The definition of what is a racist is getting more and more vague ! Nevermind, I enjoyed the article a lot!

Grabbed ‘The Straight Life’ after reading this, seems like an awesome read about Sex, Drugs and… Jazz. I’m not ashamed to say that I love my junkies in music. What’s strange about Art though is that he seemed to become even better as junkie. Compare with Keith Richards fe, who liked to claim the same, but was actually replaced very, very often in the Studio cause he couldn’t deliver, replaced by Jagger and others. So Art claims to have not practiced much, which is hard to believe, since I believe talent alone is never enough. Very unusual. Contradictionary and wild portrait that I have of him so far, can’t wait to read the book. Great article 👍

This is so great. My dad was lucky to meet Art in Ronnie Scotts shortly before he died. If he were still about he would have loved to read this. Lovely, sad tribute to a remarkable musician.

Thank you Claire! That must have been incredible, I would love to have shared just a few minutes with this man. His life is well worthy of a biography, fascinating from before birth to death.

Brilliant read about this tragic man. I remember reading that his own daughter labeled him as ‘racist and rapist’. Must buy that book, seems like a great read.