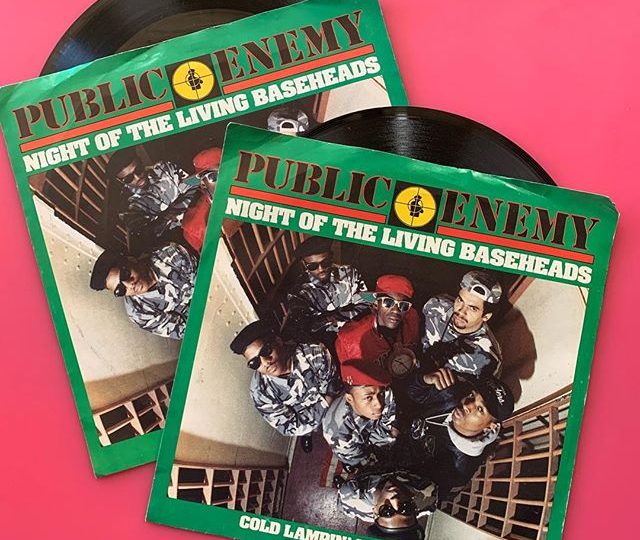

Public Enemy – Night Of The Living Baseheads (1988)

Popular music did not have much impact on me as a child. I attribute this to the fact that 1970s pop was universally dreadful. Moreover, my limited exposure to it was either via light-entertainment programmes such as the Two Ronnies, or through children’s TV such as Crackerjack. The former would feature the likes of Dana and Elaine Page; the latter, pop groups featuring terrifying, heavy-set, middle-aged men in drag. Men who looked like they had just set down their shovels and hods before applying make-up – the legion cohorts of Jimmy Savile. As for the Bay City Rollers, well, they looked like the kind of yobs I saw in the streets, throwing bricks at the police.

My youthful conservative disapproval extended to the music which I found universally maudlin and inane. I remember with particular clarity vomiting blood to Save Your Kisses For Me. OK, I was in hospital at the time and had just had my tonsils removed, but I recall the grim satisfaction and sense of catharthis.

It was business as usual in 1977 with one of my most hated songs of all time – Rock Bottom by Lynsey de Paul and Mike Moran. There was no escape from this song. It was on the radio, on the television; my father would sing it incessantly and get the words slightly wrong. In researching this piece and playing the song again it immediately reminded me of the boredom and powerlessness of being a child. Worse, I realised that my misanthropy had begun much earlier than I imagined – aged 8, I wanted to destroy the world. Rock Bottom is music for people who don’t like music; who think that music should be jolly and fun; people who would never entertain the idea that vomiting blood to Brotherhood Of Man could be pleasurable.

But it was also 1977 when I finally realised there was an alternative. However, it was not the Sex Pistols or the Clash – the system was completely and utterly effective at censoring such music and it was not until the early-mid 1980s that people in Northern Ireland first heard about punk. No, my road to Damascus moment was, of all things, Black Betty by Ram Jam. I saw this very performance on the television at the time. I vividly recall my hot confusion at the band’s thrusting impudence; it felt immoral and dirty; even blasphemous. I felt ashamed that someone might learn that I had unknowingly seen the clip. The riff scythed around and around in my head.

On or around the same time I also saw Elvis Costello playing Watching The Detectives on Top Of The Pops. I was watching it with my babysitter and I recall asking her who the silly sweaty man was with his silly glasses and why was he silly and did he know he was silly? He was so silly – was he an idiot? But something about the performance made an impression nevertheless; I remember realising that he was telling an important story and that better still, neither he nor the music was in any way jolly.

Ten years later I was stepping out of the lift when I heard a dreadful noise. Was it a car alarm? I walked along the hall and looked into the bedroom. A bloke was sitting on the bed. ‘Alright man?’ he said. ‘What IS this?’ I said. He smiled. ‘Public Enemy, bruv’. He turned it up further. It was Rebel Without A Pause. It was a godawful racket. It sounded like the end of the world. With car alarms. It was the least jolly and most impudent music I had ever heard.

Until that point I thought I was cool. I had always liked hip hop (or ‘rap’ as I thought it was called), from The Message onwards. Only days previously I had been playing Mantronix’s superlative Who Is It? in my bedroom when a fellow countryman of mine had wandered in. ‘Dats not music,’ he opined. ‘Dats just a computer’. In my memory he is actually holding a bodhran as he says this. Maybe that is just an embellishment added by my brain that reflects my own prejudices, but whenever I see someone with a bodhran, I feel the urge to play Mantronix at them really loudly.

Later that afternoon I went into town with my new friend – Dan. We walked around Affleck’s Palace and I recall buying a white vinyl copy of the Damned’s Phantasmagoria. Perhaps if one put were to put a CD of Rebel Without A Pause into an Opposite-Making Machine, a white vinyl copy of Phantasmagoria might come out the other end. I recall Dan’s genuine and polite interest in, and complete ignorance of, the Damned, and my faint embarrassment and dawning realisation that my music was anachronistic, as was its format and the very concept of record collecting.

Nevertheless I had the wit to buy It Takes A Nation Of Millions To Hold Us Back when it was released. It’s hard to imagine now the outrage this record created; I think white America would gladly have lynched all of Public Enemy – the USA’s standard response to creativity, intelligence and honesty in art. It’s also hard to imagine a record being so noble; individuals being so willing to stand in the eye of the storm, or a band so on top of its media game.

Night Of The Living Baseheads is my favourite track from the album. Aside from being sonically brilliant from beginning to end and honest and righteous in its subject matter, Public Enemy also produced an astounding video which subverts every stereotype going and even mocks the band.

14 years later I found myself sitting with 499 other white guys in their early 30s awaiting enlightenment at ‘an evening with Chuck D’ during which, we were promised, Chuck would ‘discuss and debate’. Eventually Chuck ambled onstage, holding a beer. I guess I had been expecting Louis Farrakhan. Instead we got someone a bit like your mate Dave who has come round with a 6 pack to watch Top Gear and unexpectedly found himself on Parkinson. Chuck was incredibly lacking in opinions; down to earth; bemused even. So much so that I cannot remember one goddamn thing that he said. Perversely this made me warm to him all the more.

All I can remember of the evening is some bloke from Peterhead continually asked Chuck questions in thick Doric, much to the annoyance of the crowd who a) wanted him to shut up and b) kept having to translate for him. At one point he asked Chuck if he would bring Public Enemy to Aberdeen. ‘I’ll see what I can do man.’ said Chuck.’ ‘Nae you willnae,’ replied the heckler, ‘you all say that’. ‘OK man,’ said Chuck, ‘I promise you the next time we come to the UK we will play Aberdeen. That’s a promise, man.’

The show finished. We trooped out, unenlightened.

A year later at breakfast I opened the NME with my usual theatrical weary sigh. On page 3, under the rubric ‘Public Enemy Announce UK Tour’ was the date for 13th April – Aberdeen Music Hall.

by Mike McConnell

Wow, wonderful piece! This record also had a huge impact on me, ‘nobel’ as you put it, is the best way to describe it.

Thank you, Andre

Lovely story, I enjoyed reading it. Thanks!

Thanks, Martin!