Crazy Turks – 4 / CEM KARACA & the Psychedelic Working Class

How the Soul of Anatolian Rock Ended up Making the Greatest German Protest Record

Constructing a daydream often starts with the same setting: I’m in a stripped down universe that must be close to the gates to heaven due to its bright nebula of bliss, and I have to give an angelic answer to a specific question of unquestionable importance. It can be of philosophical or theological nature, it can be about chosing between Elvis and Iggy Pop, or between cigarettes and red wine, or it can be the question about which Turkish artist I would marry if I had to chose between all of them. The transcendal setting requires more than superficial or too obvious lust-driven choice, so I am going to opt for: Cem Karaca.

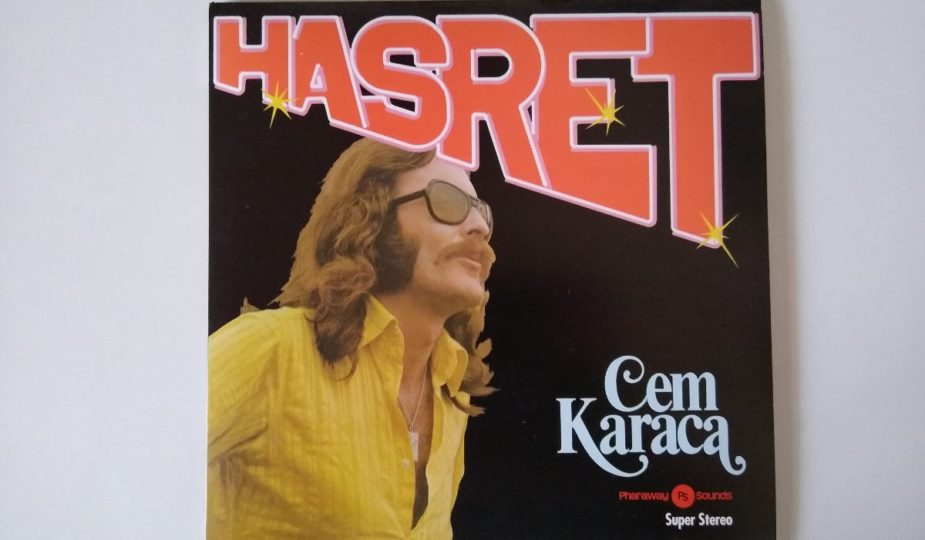

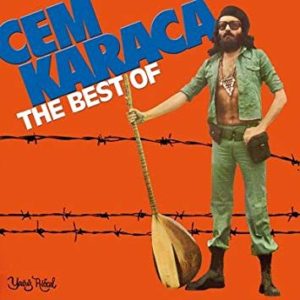

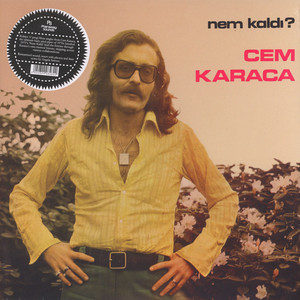

Not the most handsome of them, still Cem Karaca has it all: a mustachioed swagger, brains, politics, and a psychedelic and dramatic artistry blending Anatolia with the West, and then blending both with an universal message. A beautiful human and true artist- driven, full of clarity and a rare integrity. With his biggest romance being that to his Turkish homeland, he was a nationalist socialist who was forced to spent years in German exile in Cologne, where he ended up making the greatest German protest record with Die Kanaken (1984).

Cem Karaca was born in Istanbul in 1945, to an artistic upper-class family of Armeninan-Iranian and Azerbaijani origin that was involved in theatre, opera, and film. As teenager, and while visiting elite schools, Cem did what every young boy of the right mind would do: he first started a rock cover band called The Dynamites to impress girls, and then joined an Elvis cover band called The Jaguars to worship the one and only earthly king.

Life changed when Cem Karaca did his mandatory military service for a 12 months. During his time as soldier, he got to know the country outside of Istanbul and got in touch with Anatolian people and culture. This time served as first serious encounter with Anatolian music, but also as natural initiation into a socialist ‘brotherly’ thinking triggered by the love for the homeland and its people. Cem recalled: „During my time in the army I heard an Anatolian soldier playing the saz. Up until then, I had always found this music to be primitive and boring, but that moment the sound made me lose it. I realized that this instrument revived and expressed my feelings, and I also realized that no Western music would ever be able to express that. I found the essence that I could not find in Rock’n’Roll.“

Life changed when Cem Karaca did his mandatory military service for a 12 months. During his time as soldier, he got to know the country outside of Istanbul and got in touch with Anatolian people and culture. This time served as first serious encounter with Anatolian music, but also as natural initiation into a socialist ‘brotherly’ thinking triggered by the love for the homeland and its people. Cem recalled: „During my time in the army I heard an Anatolian soldier playing the saz. Up until then, I had always found this music to be primitive and boring, but that moment the sound made me lose it. I realized that this instrument revived and expressed my feelings, and I also realized that no Western music would ever be able to express that. I found the essence that I could not find in Rock’n’Roll.“

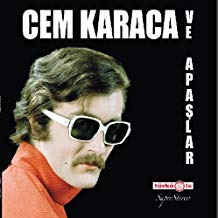

After his military service, Karaca joined the beat group Apaşlar (The Apaches), and together they attended a popular national music competition Altin Mikrofon, where they won the second prize with their song ‘Emrah’, but got more attention than the actual winner. The record that Cem Karaca made with them was still more beat-oriented and with three songs in English language, but with every record made, Cem would find his very own, more traditional and psychedelic Anatolian sound. After Apaslar, Cem Karaca founded another group, Kardaşlar, until he worked with the legendary backing group Moğollar, which had also backed artists such as Bariş Manço, Selda Bağcan, and Erkin Koray. „Cem Karaca ve Moğollar“ lasted for two years and resulted in one of Cem Karaca’s biggest hits, ‘Namus Belasi‘.

After his military service, Karaca joined the beat group Apaşlar (The Apaches), and together they attended a popular national music competition Altin Mikrofon, where they won the second prize with their song ‘Emrah’, but got more attention than the actual winner. The record that Cem Karaca made with them was still more beat-oriented and with three songs in English language, but with every record made, Cem would find his very own, more traditional and psychedelic Anatolian sound. After Apaslar, Cem Karaca founded another group, Kardaşlar, until he worked with the legendary backing group Moğollar, which had also backed artists such as Bariş Manço, Selda Bağcan, and Erkin Koray. „Cem Karaca ve Moğollar“ lasted for two years and resulted in one of Cem Karaca’s biggest hits, ‘Namus Belasi‘.

Karaca has always been political in his attitude and lyrics- whether it was posing in front of a huge graffiti saying “Poverty Can’t Be Fate“ for a record cover, or chosing ‘1 Mayıs (1 May)’ as reference to the socialist International Workers Day as album title- Cem never forget the Anatolian people and their stories of injustice and poverty that he got to know during his military service. But it never went to an extend where accusations of him being a Marxist-Leninist subversive and revolutionary would have been justified.

Cold War- years went by, but political balance and peace did not settle in Turkey. The rumors had come out. With armed conflicts and streets washed with blood, the footsteps of the upcoming coup were heard. In an era when hearing gunshots on the streets was normal, and where he saw his friend being arrested for wearing a red jacket, Cem Karaca did not allow politics to cover his art, he wanted to sing. He was in Germany for a tour, when the CIA-backed military coup in Turkey happened on 12 September 1980.

Cem Karaca was trapped in German exile for the next 7 years. He heard that his father had died, but couldn’t return to Turkey for his funeral, and refused to return for a trial for “treason, communist propaganda, and the involvement in rebel organizations”. Authorities claimed that Karaca (among several other artists) and his social protest songs were calling citizens to a bloody war against the state. In his absence, he was deprived of Turkish citizenship in 1983. Karaca was stuck in exile in Cologne, away from his beloved country that he had sung so many passionate songs about.

Cem Karaca was trapped in German exile for the next 7 years. He heard that his father had died, but couldn’t return to Turkey for his funeral, and refused to return for a trial for “treason, communist propaganda, and the involvement in rebel organizations”. Authorities claimed that Karaca (among several other artists) and his social protest songs were calling citizens to a bloody war against the state. In his absence, he was deprived of Turkish citizenship in 1983. Karaca was stuck in exile in Cologne, away from his beloved country that he had sung so many passionate songs about.

Away from family, friends, and artists he worked with, and stuck in a country he didn’t speak the language of, difficult times began. But being a true artist driven by the inevitability of art and justice, Cem immersed in his new environment which gave him plenty material for his thoughts and songs. Not only was Cologne an open cultural city which hosted bands like CAN, that were supported by the enormously good infrastructure of the public broadcaster WDR, but it also was host to 1,5 million Turkish ‘Guest-workers’. Millions of people from Anatolia, Greece and Italy had left their villages for a German call for guest-workers in the 60s, when the country couldn’t handle it’s miraculous economic post-war growth anymore and needed some good workers to do the hard and dirty jobs. And while all of them were targets of racism, Turkish people were hit harder because they were Muslims on top of being foreigners. For a Turkish worker it was normal being offered pork on a daily basis for a good mockery, not to speak of that there was no way for them to practise their religion properly with prayer rooms back then. Cem Karaca reduced the migrant / guestworker misery and melancholy to a simple, stabbing formula: “They called for workers, but humans arrived.”

Cem recalled these times in later years: “A section of the German press tried to instrumentalize me for their anti-Turkish and pro-Western propaganda, which is always also a way of saying “Hey, Hans! Be thankful of this ‘democracy’ the state grants you, and be still”. After I noticed that, I left out topics related to Turkey from my songs. There were 1.5 million people with a Turkish passport living in Germany, I tried to express their problems, and turned to the German language. Everything changed after that. The guys didn’t feel pity for me anymore, but looked at me with respect. I jumped on their floor.”

Recorded in German language, in his album Die Kanaken (which is a racist slang term for Turks, resembling the German word for ‘cockroach’) Cem Karaca dissects the immigrants’ disrooted lives and struggles, the collective experience of being second class citizens due to racism and the alienation which that triggers. He addresses the never-ending melancholy that indistinguishably blends with the regret of leaving the homeland for no matter what. By examining the Turkish immigrants’ place in German society and particularly working class and industrial life, Cem Karaca incidentally draws an accurate picture of the Western working class as such. Die Kanaken is very much about Turks, but it is also very universal. A testament of being the weakest link in society, of “trading in humanity for a shift in the assembly line”. At this point, we should recall that Karaca was born into a wealthy family of artists and visited the best schools in Istanbul.

Recorded in German language, in his album Die Kanaken (which is a racist slang term for Turks, resembling the German word for ‘cockroach’) Cem Karaca dissects the immigrants’ disrooted lives and struggles, the collective experience of being second class citizens due to racism and the alienation which that triggers. He addresses the never-ending melancholy that indistinguishably blends with the regret of leaving the homeland for no matter what. By examining the Turkish immigrants’ place in German society and particularly working class and industrial life, Cem Karaca incidentally draws an accurate picture of the Western working class as such. Die Kanaken is very much about Turks, but it is also very universal. A testament of being the weakest link in society, of “trading in humanity for a shift in the assembly line”. At this point, we should recall that Karaca was born into a wealthy family of artists and visited the best schools in Istanbul.

“Come on Turk, drink German beer,

then you are also welcome here.

Allah gets disposed with a ‘cheers’,

and you get a bit more integrated.

You stink of garlic – leave it out

eat bacon with Sauerkraut.

And if you train dogs instead of children,

you are almost integrated.

Your harem pants only disturb

please wear your legs and head bare.

If politically you are not interested,

then you are finally integrated.

As garbage collectors we already like you

get at the end of the queue when it comes to wages,

but step forward when it comes to getting dumped,

then you are over-integrated.“

Cem Karaca certainly didn’t expect to be banned in Germany, too- but not by the Germans: while touring the country, the Marxist Kurdish-Turkish community tried to use him for their case and invited him to concerts. His then wife Savrun Bari recalls one specific and fateful concert night from 1983: “It was one of these concerts organized by F…F, he organized almost every concert back then. On all of these concerts there was this map. The artists taking the stage would have to play in front of a huge map of an utopian Greater Kurdistan that stretched from Turkey over to Syria, Iran and Iraq. The word ‘Kurdistan’ was written over half of Turkey. Cem said “That map has has to be taken down, otherwise I won’t go on stage. I won’t perform in front of that map and flag.”And indeed, the map and flag were taken down. But Cem never got invited to do concerts again for his last five years in exile.

He got invited to a meeting by the new Turkish Prime Minister Turgut Özal though, who showed great efforts in the matter and issued an amnesty for Karaca and other artists in the same situation. Like all of them, Karaca returned to Turkey. Cem Karaca continued his big career where he had left it 7 years ago, frequent appearances on the public broadcaster TRT included. On his return, he kissed the hand of Prime Minister Özal as common Turkish gesture of respect, which some on the political left condemned as a sign of betrayal of the fight. But Cem Karaca was never a separatist- that was what the Turkish Militarists had gotten wrong about him in the first place. Cem Karaca’s matter was always about uniting, it was about brotherhood, bringing people closer together. It was also about patriotic love and ache, and a revolutionary claim to belong, or as he articulated it simply in one of his songs: „This country is ours.” And the truth is simple as that.

How utterly wrong the Coup d’État- officials were in condemning these artists to exile and endless yearning for their homeland and its people, making them pen the songs which are now Turkey’s new national anthems. In the end, Cem Karaca and his likes proved to be the true patriots. Where did he take the strength to follow his path undeterred and with integrity in face of injustice and bad fate and injustice? From deep conviction, but also deep belief. “Yok edin insanın insana kulluğunu – End man’s servanthood” he sang in his songs, reflecting nothing else than the islamic doctrine of not being slaves to other humans, your passions, or materialism. Sounds just like socialism.

His wife recalls how Cem Karaca closed his eyes forever on a Sunday morning in February 2004: „His last words were ‘Allahu Akbar – God is supreme’“. Heaven is a psychedelic, flared place now.

by Saliha Enzenauer

(Read all Crazy Turks parts here)

Saliha,

I am once again educated on another artist that I would have never heard of if you did not write this multilayered, thoroughly researched article. It is definitely eye-opening to read about his integral role in Turkish history and his exile in Germany and political/social lyrics about the Turkish refugees. Thanks for sharing another piece in your Turkish music series.

Thank you Mark, Cem is a very special artist. How about the Turkish version of “The Exorcist” next? 😉

His moves towards the end of the second video are amazing! He lives the music! I must explore him, thanks for this recommendation. Love your page, stay safe.

Total boss. Thank you & enjoy Cem.

This series never cease to amaze me, it feels like a whirlwind of inspiring life experiences, unexpected history lessons and great cultural wealth. Turkey has outstanding artists, and Cem Karaca is no exception. I´ve been researching more, and it´s clear that he has a very strong and solid fandom. As you implicitly said in your review, he deeply felt and understood the transformations of his homeland. I admire the fact that he fought for social justice, always staying true to his ideals.

Thank you Saliha. You´re making me discover artists who are totally unknown in this region.

Thank you Octavio, I’m glad you like these stories as much as I enjoy writing them. But I know that you’re constantly exploring music, film and art outside of the norm and boundaries, you’re keeping yourself a curious spirit and open mind / senses. Next up are some surreal insanities from the film genre. Absolutely crazy & arty & intruiging- I’ll be interested to hear what you think of them. Stay tuned!

I´m looking forward to discover new artists, Orhan Gencebay´s and Müslüm Gürses´ most acclaimed records are now on my habitual playlist, Cem is next.

“Arabesk” is finally starting to get inside my brain, your insightful stories and reviews are necessary- an instant motivation for the readers (most people in Latin America don´t know anything about Turkish culture).

Oh, surreal insanities and weird artsy cinema. That´s going to be a hell of a ride, I´ll stay tuned !.

“Die Kanaken” got rediscovered a few years ago by the German media, but I never knew about the Karaca’s story. Great read! I managed to find a decent copy of the record for 80€. The lyrics have never been more relevant:

Hey – von der arbeitssuche

Bin ich total geschlaucht

Egal wo ich auch hinkomm

Ich werde nicht gebraucht

Ich glaub schon selber

Ich bin nichts wert

Da ist doch was was verkehrt

This series of articles are among the very best on Vinyl Writers. Saliha, you bring to these artists work to life. Informative, interesting and… fun. The only down side is that I want them to be longer. Cem Karaca is one of the finest and most important musicians to step onto the global scene. His ability to mix his political voice with amazing music is a rare talent. Thank you for bringing him to the VW audience. Can’t wait for the next article.

You have such a fantastic ear for good music. Proof is that now you’re in love with arabesk and nothing else will do!

“They called for workers, but humans arrived” says it all. Fantastic feature.

Brutal line, truth hurts.

Love Cem Karaca, what a voice! Let alone the cool looks!

He’s the coolest, what charisma!

Brilliant once again. These are such a rich source, I feel educated and entertained. Your last part with the blasphemous vibes was simply epic. More please!

Thank you! Another part is coming soon, stay tuned!

Amazing life! Seems like he was a very special artist. Love these Turkey series and how you tell us more than just about the music – it’s cultural studies. Thanks, you’re awesome!

Thank you, another part is already written, with more to come- film is next.