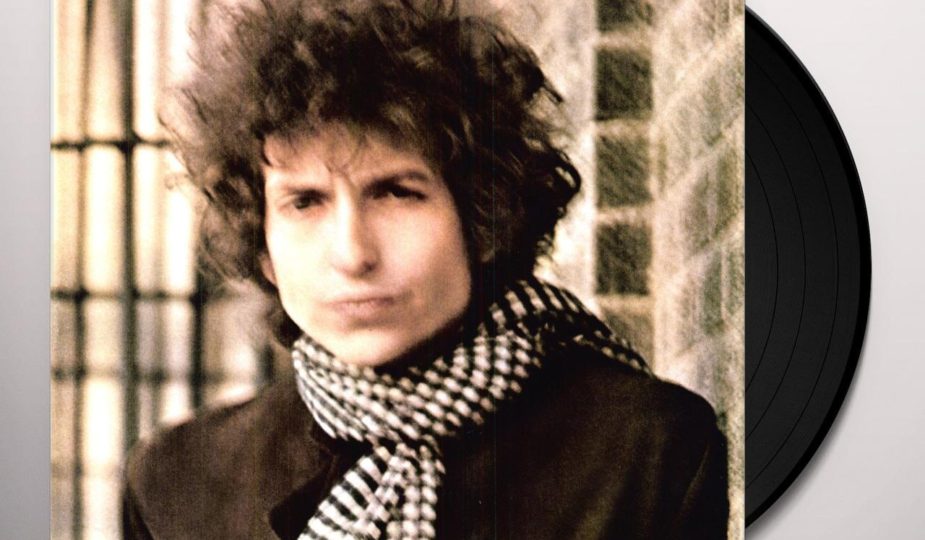

Bob Dylan – Blonde On Blonde (1966)

The story behind Bob Dylan’s masterpiece, Blonde On Blonde, is one of the most iconic in all of popular music. Dylan, coming off of touring for the equally magnificent Highway 61 Revisited, took some of the Hawks, his touring crew, and went into the Columbia Studio in New York to create his next musical work. After frustrations reached fever pitch and productivity plummeted, Dylan packed up his equipment, took his band, and dragged them all the way down to the Columbia session studio down in Nashville, Tennessee. There, he reached out to some members of the thriving music scene, drafting a ramshackle band of musicians into the sessions of what would become his magnum opus.

It was that story that first inspired me to find Blonde On Blonde on Apple Music, an act mostly done in boredom due to the fact that my flight from Minnesota had broken down, stranding me in a city where the highest temperature of the day was negative. Some sort of convoluted sentiment was involved, noting that Dylan was indeed a Minnesotan, and listening to a Minnesotan artist in Minnesota would be poetic in my pretentious mind. I was aware of the prolificness of Dylan’s 60’s output, so I went into the record assuming that I’d hear the apex of his sound, something streamlined and focused beyond all measure.

Which is why the opening track, “Rainy Day Women #12 & 35”, shocked me more than the frigid hellhole of Minnesota ever could. I actually double-checked my headphones to see if they were broken. There is no tasteful guitar. No tasteful anything, for that matter. Just the plodding drums and bass, the tambourine slightly out of sync, inebriated, rinky-dink piano, and the dissonant, mournful howls of the harmonica and a muted trumpet, all seemingly detached from Dylan’s near-sobbed vocals and the egging-on of the audience. Upon further inspection, past the pun that correlates the punishment of stoning with, well, getting stoned, the lyrics sound confrontative, maybe a bite back at the folkies Dylan disavowed when he went electric. Then again, it could just be about weed. It’s cheeky, and considering that it’s the first taste of the album given to listeners, it’s unbelievably daring. But whatever it’s about, “Rainy Day Women” is sneakily brilliant. It’s so completely juvenile, yet somehow, in a way unique only to Dylan, it’s complex and ambiguous, a gutsy risk that makes for an off-kilter hallmark of his catalogue.

On Blonde On Blonde, Dylan’s lyricism, for which he rightfully was awarded the Nobel Prize for in 2016, is clever, insightful, and beautiful, showing a literary giant at the peak of his career. “I Want You”, even as one of the most accessible songs of the album, packs in allusions to Islamic tales and mentions a controversial interaction with pop artist Andy Warhol, joined by a pretty forceful organ. “Absolutely Sweet Marie”, with its iconic Dylan-isms (“But to live outside the law, you must be honest,”) places guitar fills behind a pounding, brusque snare, making for another late album highlight. But it’s a Dylan fan favorite, the epic, 7 minute long “Visions of Johanna” where Dylan truly reaches the epitome of everything he’s done as a lyricist, an abstract odyssey vaguely about 2 very different women, the passionate Louise, and the aforementioned, seemingly unattainable Johanna. Peppered with (more) Dylan-isms like “Name me someone that’s not a parasite and I’ll go out and say a prayer for him”, the lyrics are fragmented as if he’s writing his every thought onto paper, evoking a sense of deep longing, passion, and mystique. As with most of Dylan’s best songs, “Johanna” is vivid and dripping in imagery. The music is sparse, but it perfectly complements the beauty of Dylan’s lyrics, soft guitar giving space to Al Kooper’s organ fills and Joe South’s slightly twanging bass to create a gorgeous backing for one of Dylan’s most gorgeous works of writing.

It’s Dylan’s chemistry with the supporting band behind him, cobbled together from his touring entourage, studio musicians from New York, and local musicians in Nashville, that gives Blonde On Blonde that sprawling, bewitching beauty it possesses. The sonic template maintains consistency throughout the album, a hybrid of acoustic and electric guitars, bass, keys, and organ. Of course, Dylan and Charlie McCoy’s harmonicas are present in almost each and every song, whether pounding through Chicago Blues on “Pledging My Time”, knocking out uptempo rockers like on “Obviously 5 Believers”, or reaching anthemic, organ-driven peaks on “One Of Us Must Know (Sooner or Later)”. “Sad Eyed Lady Of The Lowlands” is a masterful display of dynamic restraint from Dylan and his band, a stunning 11-minute long ode to his lover Sara Lownds. In a comic turn, Dylan’s band, assuming that he only had two or three verses, kept picking up as the hook arrived in hopes that the song would end, only to be put down by Dylan’s return to his harmonica and another verse. The result is a song that ebbs and flows woozily, never breaking the spell as it goes back and forth between loud and quiet.

But if you ask me where Blonde On Blonde reaches the height of its sonic mastery, I’d have to point to another 7 minute epic, the brilliant “Stuck Inside of Mobile With The Memphis Blues Again”. Surreal, arcane, and wildly abstract, “Stuck Inside of Mobile” could be praised alone for its lyricism. However, it’s here that Dylan’s backing band truly reaches their musical peak, a stunning exhibit of their musical virtuosity. Al Kooper’s organ fills, more full bodied than on “Sooner or Later”, take a life of their own, gliding along Dylan’s grounded acoustic, Joe South’s delicate bass, and Kenny Buttrey’s snare fills. Complimented on the stereo mix by some great electric guitar fills, Kooper’s organ performance is nothing short of intoxicating. However, that’s not to shortchange the others, as that backbone of “Stuck Inside of Mobile” keeps it energetic, vigorous, and lively. Poetic, esoteric, and practically perfect on a sonic level, “Stuck Inside of Mobile” stands as yet another stunning testament to Dylan’s lyrical gift, but it also stands a testament to the talent of the backing band behind him as well.

Blonde On Blonde, more than 50 years later, still stands as maybe the defining work of one of the greatest poets of our time, a wonderful marriage of Dylan’s lyrical genius and the brilliance of the ensemble behind him. The album’s sprawling beauty captivates on first listen, as it did to me in Gate 33 of Minneapolis-Saint Paul Intl. But the true power of Dylan’s work is how it captivates on every listen after that first listen, its serene poeticism never feeling dated, an immortal album that still sounds like you’re listening to it for the very first time.

by Raghav Raj

I was curious if you ever considered changing the layout of your site? Its very well written; I love what youve got to say. But maybe you could a little more in the way of content so people could connect with it better. Youve got an awful lot of text for only having 1 or 2 pictures. Maybe you could space it out better?

Beautiful writing. Inspired to revisit this album.