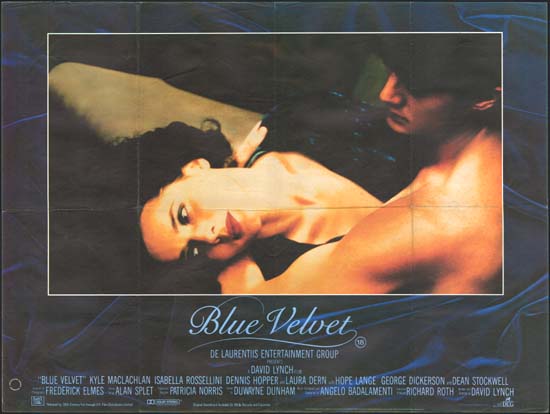

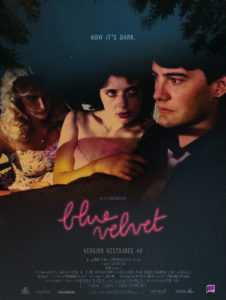

A Psychosexual Classic: Blue Velvet (1986)

For the past thirty years, it is evident that the weirdest and most surreal place in cinema emerges from the mind of David Lynch. Since his debut film, the strange and avantgarde Eraserhead (1977), much of Lynch’s output has been the perfect fuel for nightmares: mutated creatures, bizarre murder mysteries, fractured psyches, disturbing dreams, etc. Before he traveled down to complex films like Lost Highway (1997) or Mulholland Drive (2001), Lynch was exploring the dark underbellies of American suburbia. He suggested that one doesn’t have to travel far in search of trouble; indeed, one only needs to closely examine those seemingly perfect houses and perfectly mowed green lawns to find something dark and sinister lying beneath. This effort culminated in the popular and acclaimed television series, Twin Peaks (1990-1991), but it really began a few years earlier with Blue Velvet (1986), the film that still stands as Lynch’s masterwork of psychological horror.

Blue Velvet’s opening sequence is filled with great symbolism. Elegant opening credits are placed in front of a blue velvet curtain, the background is enriched by a thunderous and immersive classical composition by Angelo Badalamenti. After this, we fade into the clear, cloudless blue sky as Bobby Vinton‘s melancholic ballad “Blue Velvet” begins to play. The camera then pans slowly down to a garden fence, where we see wild flowers growing strong and healthy. In slow motion, we also see a fire engine that doesn’t seem on it’s way to put out any fire. On the contrary, it travels down the road with parsimony. A firefighter greets the neighbors, everyone’s faces is shining with happiness: the everyday atmosphere is greatly idealized. The camera then pans into the house behind the aforementioned fences. We see an older man watering flowers on a calm Sunday morning. Peace reigns in Lumberton, a small town in America. However, something unexpected happens: the man’s hose gets tangled up and forms a knot that jams it. The old man suddenly faints as a result of a presumed heart attack that makes him fall to the ground. A dog approaches and begins to play with the stream of water that gushes out of control. Then, to the viewer’s surprise, the camera explores the underground. Lynch shows us what lurks under the weeds: huge and defiant ants and insects that move frantically, in clear contrast to the calm that we had seen before. Even in the most peaceful situations, horror is hidden somewhere.

Moments after the opening, Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) is walking across a field. The stricken  man’s son has been called home from school. He can’t help his incapacitated father, and he has nothing to do. While looking for pebbles in the field, Jeffrey sees something else: a decomposing, severed human ear (Lynch’s wink to Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou). Jeffrey will take his discovery to the police, with detective Williams (George Dickerson) being in charge of the case. In the face of Williams’ silence, it will be his daughter, Sandy (Laura Dern), who will inform Jeffrey of some details that could be related to the mysterious ear. Soon, Jeffrey discovers the existence of the singer Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini) and sneaks into her apartment in search of answers. The dangerous curiosity that moves Jeffrey is the same which the viewer feels- Jeffrey is a voyeur, like the viewers themselves. From that point on, Jeffrey and Sandy’s world will crumble by leaps and bounds as they discover a very dark and twisted reality, full of violence and madness. Also, Jeffrey will be involved in a unique and dangerous love triangle: while his relationship with Sandy couldn’t be more conventional, his upcoming relationship with Dorothy will reach bizarre heights. Both women complement each other perfectly. One represents the ideal girlfriend that every “good boy” would want, whereas the other represents a dark fantasy. By entering into a relationship with Dorothy, Jeffrey will grow out of being a teenager and discover that some wishes are better left unfulfilled.

man’s son has been called home from school. He can’t help his incapacitated father, and he has nothing to do. While looking for pebbles in the field, Jeffrey sees something else: a decomposing, severed human ear (Lynch’s wink to Buñuel’s Un Chien Andalou). Jeffrey will take his discovery to the police, with detective Williams (George Dickerson) being in charge of the case. In the face of Williams’ silence, it will be his daughter, Sandy (Laura Dern), who will inform Jeffrey of some details that could be related to the mysterious ear. Soon, Jeffrey discovers the existence of the singer Dorothy Vallens (Isabella Rossellini) and sneaks into her apartment in search of answers. The dangerous curiosity that moves Jeffrey is the same which the viewer feels- Jeffrey is a voyeur, like the viewers themselves. From that point on, Jeffrey and Sandy’s world will crumble by leaps and bounds as they discover a very dark and twisted reality, full of violence and madness. Also, Jeffrey will be involved in a unique and dangerous love triangle: while his relationship with Sandy couldn’t be more conventional, his upcoming relationship with Dorothy will reach bizarre heights. Both women complement each other perfectly. One represents the ideal girlfriend that every “good boy” would want, whereas the other represents a dark fantasy. By entering into a relationship with Dorothy, Jeffrey will grow out of being a teenager and discover that some wishes are better left unfulfilled.

Every macabre story needs a villain, and Frank Booth (Dennis Hopper) soon makes his appearance. Frank  suffered from a rampant childhood abuse trauma that unloads on the figure of Dorothy, who has to give in for fear of losing her son and husband, both kidnapped by this dangerous individual. For his sexual pleasure, Frank initiates a very curious and sinister ritual with Dorothy. First of all, violence is always present in his acts. Without beating Dorothy, he cannot get aroused. Second, he doesn’t consent to being looked into his eyes. Third, when he begins to stimulate himself, he pulls out a mask and breathes in a mysterious gas that makes him even more aggressive. He later visits “The Slow Club” to watch Dorothy perform a cover of Bobby Vinton’s “Blue Velvet”, tearfully cradling a piece of blue fabric he cut from Dorothy’s robe during the sexual assault. Inside the character of Dorothy, we can also discover traits that stem directly from Frank’s abusive behavior. As soon as she begins her relationship with Jeffrey, she unleashes the same bizarre sexual rites on him.

suffered from a rampant childhood abuse trauma that unloads on the figure of Dorothy, who has to give in for fear of losing her son and husband, both kidnapped by this dangerous individual. For his sexual pleasure, Frank initiates a very curious and sinister ritual with Dorothy. First of all, violence is always present in his acts. Without beating Dorothy, he cannot get aroused. Second, he doesn’t consent to being looked into his eyes. Third, when he begins to stimulate himself, he pulls out a mask and breathes in a mysterious gas that makes him even more aggressive. He later visits “The Slow Club” to watch Dorothy perform a cover of Bobby Vinton’s “Blue Velvet”, tearfully cradling a piece of blue fabric he cut from Dorothy’s robe during the sexual assault. Inside the character of Dorothy, we can also discover traits that stem directly from Frank’s abusive behavior. As soon as she begins her relationship with Jeffrey, she unleashes the same bizarre sexual rites on him.

Lynch immerses us in this nightmarish world thanks to a randomly found object and emphasizes this fact by subsequently having the camera enter through that initial decomposed human ear. A series of bizarre, surreal, and almost unexplainable situations will happen throughout the film. When the nightmare ends, Lynch will make us leave that world through another ear: the one of a more adult Jeffrey who has accepted his role in the world and its complexity. Lynch gives his film a circular structure. The beginning and the end are very similar, but the viewer and the characters are no longer the same. Jeffrey and Sandy will learn that the world is not as beautiful and ideal as it seems. In the end, Jeffrey prefers to stop being curious and decides to live a quiet life.

The fine line that divides reality and imagination is constantly present in this film, where Lynch creates a palpable and credible oneiric reality. Despite distorting time, slowing down images, and showing disturbing scenes that could only take place in dreams, the atmosphere is completely believable. Nothing better than Sandy’s words to define Blue Velvet and, by extension, all of David Lynch’s surreal works: “It’s a strange world, isn’t it ?”

by Octavio Carbajal González