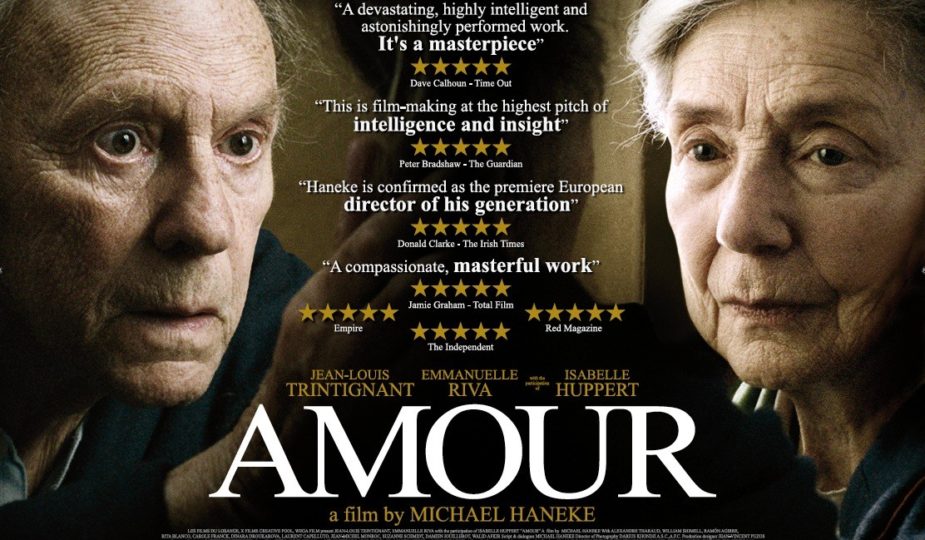

Amour (2012)

True, we love life, not because we are used to living, but because we are used to loving. There is always some madness in love, but there is also always some reason in madness.

Friedrich Nietzsche

For those who write, watching a film by Austrian auteur Michael Haneke requires preparation: sitting down, meditating for a moment, taking an impulse through a sigh and preparing to let yourself be carried away by an aesthetic pleasure that will also make you suffer: for its rawness, for its pessimism, for reproducing life, for making cruelty a poetry.

The word “love”, in any language, is difficult to define. In Spanish, for example, it has more than 14 different meanings, most of them imprecise. And, if this wasn’t enough, many times we want to distinguish between the different types of love that exist: towards parents, children, friends, to a country, to a supreme being, to oneself. But most of the time, the immediate identification of the word has to do with the partner, the loved one.

Haneke’s 2012 masterpiece Amour tells the story of Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) and Anne (Emmanuelle Riva), a couple in their 80s. Both are retired piano teachers who live in an austere apartment in Paris, decorated with sobriety and good taste. The film begins with a kind of prologue, in which a firefighter squad bursts into the apartment, inspects the place and discovers a corpse surrounded by flowers in the main room. Actually, from there, everything is told in flashback; the story keeps linearity in the structure, seasoned with dream sequences, a couple of brief interludes, and some emotional maneuvers of imagination.

We first see Georges and Anne attending a Schubert piano concert at the Theater des Champs-Élysées. At the end of the gala, they both go to the dressing room to congratulate the interpreter who used to be one of Anne’s students. They return home and find that the entrance has been forced. Someone tried to violate their most intimate space without succeeding, but the couple remains uneasy. Georges tries to comfort Anne, encouraging her not to let that episode overshadow the wonderful evening they had, “Did I already tell you that you look beautiful tonight?”, he ends, to lighten up the moment and reaffirm his devotion to her. When in bed later, he has problems falling asleep and, when he turns to see how her partner is doing, discovers Anne upright, staring blankly. He asks her what’s wrong, and she answers “Nothing”. The next morning, Anne is stuck with her eyes open but without conscience. When she finally comes back, she doesn’t remember anything and Georges thinks she’s making fun of him; realizing that this is not the case, he tells her that he will seek her doctor. She refuses. “We can’t pretend that nothing happened,” Georges says. At the end of this sequence, Haneke decides to insert an interlude which acts as an emotional repose and a vehicle for the transition of time, in the manner of a montage consisting of fixed, semi-dark shots of the different spaces that make up their house, corners that have witnessed, for years, the development of a solid love relationship.

In the following sequence, the daughter, Eva (Isabelle Huppert), arrives to visit her father. Anne is hospitalized and Georges informs her of the state she’s in, which is not promising. “We have always managed ourselves, your mother and I,” he points out. Before leaving, Eva tells him that upon entering the apartment, she remembered that as a child she used to listen to them make love, and how that, far from disturbing her, reaffirmed the idea that her parents loved each other and would always be together. When Anne returns from the hospital in a wheelchair and with partial paralysis of her face and body, she and Georges try to put their best face on misfortune. Anne is happy to return and she makes Georges promise that he will never, whatever happens, hospitalize her again. Anne will be largely dependent on Georges’ care, and he will have the responsibility of looking after her. Only an authentic love is capable of enduring such a circumstance. “Love demands supernatural tests”, as the Argentinian poet Jorge Luis Borges pointed out.

Haneke’s gaze, without being distracted by landscapes, focuses precisely on these two human beings locked in their space, in their world. With surgical fidelity, the Austrian filmmaker portrays the cruelty of the ups and downs in Anne’s healthcare. The good days bring hope, excitement, and encouragement. The bad days are impatient, depressing, and discouraging. Death, with that tenacious and intrusive shadow that it poses in the lives of the elderly and the sick – and which those of us who do not adjust to those circumstances tend to ignore, despite knowing of its omnipresence – displays its grotesque rituals on Georges and Anne. They are truly alone, him and her. Neither do they find refuge in God, nor do they seek his protection. It all lies in an emotional moment when the old woman wants to review and relive her life reconstructed from the fragments of a photo album “It’s beautiful,” says Anne. “What?” Georges asks him. “Life … Life is so long,” Anne decrees in one of those moments of lucidity that are increasingly scarce. The moments of memories and experiences start to disappear. Anne’s verbal coherence is fractured and her connection to the world is dissociated. Georges, in turn, loses patience. Anne tries to regain vitality through gestures of affection, she tries to recover experiences, to listen to music with Georges, which is a transcendental point of communion for them. But her resistance stands against the frustration caused by not being able to play the piano anymore, not being able to conduct herself, not being able to communicate properly. The daily physical and emotional resistance is suffocating and overwhelming.

Haneke takes absolute and powerful control of the environment in which he works, reaching peaks of perfection on a subject as complex and challenging as this one. No matter how prodigious Haneke’s talent may be, it would have been impossible for him to achieve this degree of sublimation if it weren’t for the prodigious performances of Jean-Louis Trintignant and Emmanuelle Riva. There are many emotions, ideas, flavors and lights that this work opens in our brains. The story isn’t only about love; it’s about time, resistance, and fragility. A never ending experience.

by Octavio Carbajal González

Octavio, how beautifully you write! “ watching a film by Austrian auteur Michael Haneke requires preparation: sitting down, meditating for a moment, taking an impulse through a sigh and preparing to let yourself be carried away by an aesthetic pleasure that will also make you suffer: for its rawness, for its pessimism, for reproducing life, for making cruelty a poetry.” How aptly you described the experience of watching this film. Unfortunately, there was no preparation on my end as this is my first Haneke movie viewing :). This is a beautiful film with great performances. I felt cold and isolated after watching the film. There was a sense of grief …Perhaps that was the director’s intention; the audience suffers with its protagonists. Your observation of them being alone and disconnected is so true, for me that part was most disconcerting, as in the beginning they seemed connected with the world around them. I wondered what was your thought on the segment where the director just showed a series of paintings? I was fascinated and wondered about the symbolism.

Again, really good writing, Octavio! Such an objective and beautiful analysis of a complex movie. Always look forward to your writings.

I’m so glad you enjoyed my review, Swaha. Couldn’t be more grateful with your words!.

Well, this is Haneke’s warmest film, his other works are much more controversial and divisive. I think you’re ready to watch “The White Ribbon”.

The power of this film relies on the brutal depiction of love. The “partner” or “loved one” usually takes care of our feelings, secrets, lies and ideals. It sounds scary.

Each painting creates an specific feeling or emotion, they could be interpreted as a moment of relief.

Stay tuned, we keep in touch!

This movie left me with a weird and uncomfortable feeling, really enjoyed the read.

Thanks. Haneke did his job!

Octavio,

I have not yet seen this film, however, your review is an astute analysis of the challenges and complexities of aging, communication, love, memories, relationships, time.

(Emmanuelle Riva in Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour gave such a powerful performance and Jean-Louis Trinitignant in Sergio Corbucci’s Great Silence showed how acting can deeply speak without words.)

Hi Mark,

Thank you for the kind words, I really appreciate them.

Haneke’s style is a bit different from what you’ve used to, but maybe you should give it a try.

Hiroshima Mon Amour and Great Silence are on my watchlist, they look really interesting!. Thank you for the recommendations on your most recent article, it’s a great month to explore these classic titles.

It’s a beautiful film. Love has many faces.

Absolutely. Those faces are full of complex riddles and loops.

Haneke is probably the coldest and most clinical and sadistic director of our times, and I personally don’t think that he warmed up one bit. I loved his “White Ribbon” , but I generally consider ALL of his films as horror films who play with their viewership and rely heavily on the shock and manipulation, and that includes “Amour”. This might actually be his crudest film because it comes in the disguise of an emotional story about age & decline which is naturally triggering empathy, before Haneke is inflicting the same cruelty as in “Funny Games” on characters & viewers. The crudeness starts with the opening image of the corpse of the wife surrounded by flowers, and its in this shot where the title card “Amour” appears: the morbid tone is set. And it ends with the (unsympathetic) husband beating and murdering his (unsympathetic) wife. To me this film seems like another perfidious work by Haneke in the end, especially since there is not much love or compassion between this mechanical and formally polite couple and their bourgoise facade (which is exactly the facade that Haneke loves to blow up sadistically) . But you actually touch that in your review, the many meanings of the word ‘love’, to which Haneke added a new, typically morbid, crude and unemotional one. This might be a widely misunderstood work by Haneke in my opinion. This evil man loves to fuck with his audiences. But this is just my theory!

That all being said, I must say that your review is fantastic. I’m always amazed at how eloquently you can write in English, which is a foreign language for you, and at such a fairly young age. Many native speakers never reach this level. Very impressive, and simply delicious to read- thanks for this!

Michael Haneke is a master of polarization, you don’t really know what you’ve come up against until you manage to break the giant ice block. I fiercely agree with you, his filmography is full of horror. He has nothing to fear when it comes to portray the vileness and evilness of human beings. But, he also displays moments of vulnerability. “Amour” is the biggest proof of it. I also think that many people misunderstood the message, they are falling into the trap of excessive sentimentalism, and that´s not the case here. The story goes against the widely idealized concept of love. You have a really interesting and completely valid theory, no one has mentioned it so far !.

Thank you so much for your confidence and help through this journey, I´ve noticed enormous improvements in content, development and language. It means a lot, I´m really happy with my current work. Always an honor to write for Vinyl Writers !.

Your review are so complex and insightful. You are truly moving well beyond the traditional film review. I’ve never hear of this film but I’m looking forward to taking so time with it. Thank you for always providing us with new films and challenging topics.

Thank you Shawn, I was also pleasantly surprised by the result. I started writing this review a long time ago, it was time to let it out.

I´m almost sure that you´ll enjoy this film, it´s an absolute delight for the senses. It unfolds and flows beautifully, just like the majority of albums that you recommend.

This film is not suitable for a relaxing evening. Great actors and extremely realistic playing. Anyone who wants to deal with the topics of age, dementia and hardship in love should definitely watch this film. Beautiful review.

The brilliant sensibility of this film creates frightening scenarios. We can almost smell, touch and feel the intimacy of our protagonists. We´re all gonna be there someday.

Such a wonderful review! I agree with everything you wrote. The content of the film could not have possibly done more justice to its title! This film portrays exactly what love should be and what it actually is. It is impossible to give an actual , accurate definition of “love” , at least not using words , but this film does it!

Thanks for the kind words, Monica.

That´s a really interesting observation, the events that happen between our protagonists could be considered as accurate definitions of “love”.

I’m taking care of my mother, she has Alzheimer. Intruiged to watch this now, thanks!

I’m sure you´ll feel identified in many parts of the film.

All the best for your mother, Simone.

Beautiful review! It is important that Haneke addresses this issue, since it is becoming more and more widespread and relevant, but still a taboo in society. The movie narrative has almost a documentary character, but is interrupted by scenes that force you to think through their subtle and sensitive nature. Powerful.

Thank you for reading, Wilhelm.

The concept of love towards a sentimental partner is quite glamorized and idealized. Very few dare to portray the disturbing depths of love between an elder couple. The film makes us reflect on our preconceptions about life and love. Someday we’ll identify with Georges or Anne.

It’s a beautiful film. Hard to believe that the same director who did Funny Games made this movie.

Michael Haneke´s versatility is truly one of a kind, there´s simply no one like him. His cinema is an obscure cave, full of reality.