American Psycho (2000): A Visionary and Criminally Underestimated Work on Hyperreality & Trump

ABANDON ALL HOPE YE WHO ENTER HERE

(opening lines of American Psycho)

Every time when somebody mentions the obnoxious Matrix films and babbles something about “taking the red pill“, I fantasize that Patrick Bateman comes along, presses play on “Sussudio“, and then does what he does best.

The Matrix films are works of science fiction which pretend to be an allegory to our reality, derived from Plato’s Allegory of the Cave (and Sun). According to Matrix, our world is virtual, a set-up of an external and controlling ‘real’ world, meaning that we live in a sinister parallel universe and great truth can be found behind the things- and not within them. The films promote the idea of truth-pills: a red pill that you take in order to expose the things that are hidden from us in one great conspiracy.

The Matrix‘ writers and directors- Andy and Larry Wachowski, who turned into the transgender sisters Lana and Lilly Wachowski after the films came out- revealed in August 2020 that the Matrix trilogy are „films about being transgender. That was the original intention, but the world wasn’t quite ready,“. It is a statement that goes strangely ignored, but fans should take Wachowski’s evidence serious. Not just because it is backed by the creators’ own trans-ness, but because it is as trans metaphor where the Matrix films start to make sense: as a story of physically and psychologically painful gender transformation where both the medical aspect and empowerment of the process is inscribed into the ‘red pill’.

Similarly realized one year prior to Matrix in 1998’s Truman Show, Plato’s Cave Allegory invites us to go down an endless rabbit hole in the search for a hidden reality. It is at the same time the allegory for countless neo-conspiracies that have ceased to be investigations and enlightenments but have assumed a paranoid and misinformative nature. The allegory does not work for post-modernity and its medial and virtual revolutions, because there is no distinction anymore between reality and virtual reality. What we call reality has collided and merged with virtual reality and thus became a never-ending simulation in what Jean Baudrillard calls the ‘hyperreality‘.

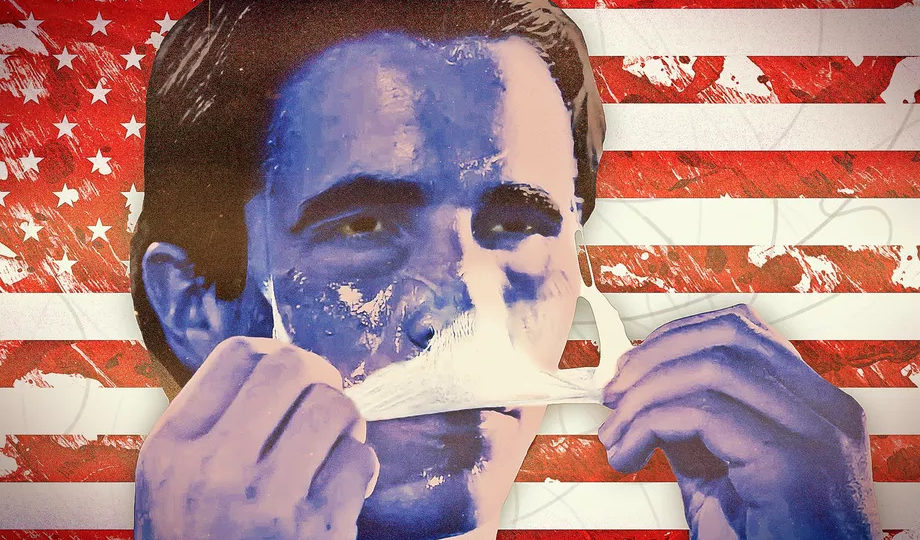

American Psycho (2000) serves as far more profound commentary on post-modern society and its loss of reality, given that the viewer makes it through its sick-humored goriness and misogyny for which the film was trashed upon its release. Based on the 1991 novel by Bret Easton Ellis and directed by Mary Harron, the film embodies the 80s over-indulgent yuppie culture with its rampant self-serving greed, aggression, egoism, overconsumption, and vacuity. Yet, if it was only for these things, the film would be nothing more than an extended biopic of Gordon Gekko with an additional crime subplot. But American Psycho proved to be a cultural critique of the social conditions of the consumer society and of what came after 21st century vulture capitalism. It is an accurate vision of our world today, a prophetic version of the American Dream, become nightmare.

Patrick Bateman (Christian Bale) is a rich, handsome young man and homicidal psychopath from the Ivy League, who like all his colleague-friends works in an investment firm in modern day Babylon and the capitol of capitalism, New York City. Bateman owns the right objects for his times: he’s living in an expensive area of Manhattan, and his posh apartment from which he can admire the Trump Tower is stuffed with expensive status symbols like a high-end stereo, designer suits, and luxury skin care products. Picked up by the film in various scenes, the book deals page after page with Patrick Bateman listing the designer objects in his apartment, defining and differentiating himself only through what he owns and thus being an object among objects himself.

It seems like we have left this heyday of consumerism behind and ushered in a new awareness of sustainability and casualness, but objects and their codes & values have changed since the 80s of American Psycho. Bateman’s expensive Chanel face cream got replaced with an organic, self-made lotion in 2020, pretentious restaurant cuisine art with trendy Asian bowls, the fitness equipment with a yoga mat, the business cards with social media profiles. But the objects more than ever serve the same purposes: identity-building upon the image manufactured through the objects with which we surround ourselves, and the codes through which these simulated identities assert an endless self-optimization to the point of dissolution. Or in Bateman’s words: „There is an idea of a Patrick Bateman, some kind of abstraction, but there is no real me. Only an entity, something illusory /…/ I simply am not there.“

The film is more than a satire on materialism that is transferable to our time, but it also points to something new that comes after the age of capitalism: the loss of reality and a new hyperreality in which everything is a simulation. Here, money and wealth are not the principal currencies anymore. An object is the materialization of something, and in the age of social networks not just selfies but also virtues have materialized and become signs and objects through which we project an image of ourselves. The loss of reality and aura, of depth and meaningfulness, must be replaced by other interpretations of experience that attempt to explain what remains. One such option is to explore the surface, or simply: banality.

In American Psycho‘s deliciously grotesque business card scene, we see these rich and Harvard-educated young men with lavish lifestyles comparing the noble surfaces and embossing of their business cards. All of them boast the title of ‘Vice President’, but we never see them do any actual work. We don’t know what their work is about, and if one of them gets murdered by Bateman and disappears, it makes no difference at all – just like when an account disappears on social media. Not only is everyone obviously replaceable, but Bateman and his colleagues repeatedly confuse one with another and call each one wrong names. Everybody is the same. Like in a beauty pageant where women of different sizes with different hair and skin colors still end up looking the same.

Something can only be inherently replaceable if it has died before and slipped into superficiality and banality. When art has died, everyone can be an artist, and everybody can replace the artist in simulating to be that artist on social media. When education has died, everybody can be smart, or a teacher. When God is dead, he can live on as an icon. When reality has died, everybody can be everything.

Bateman seems to get away with his rapes, tortures, and killings just because of this in the end: a streak of endless confusions and mix-ups, at the end of which his lawyer won’t even believe Bateman after he confesses to the murders. This ending annoyed many viewers as it suggests that the whole crimes might have been a fantasy, especially since Bateman goes back to his last crime scene, only to find a neatly renovated apartment instead of corpses and blood slaughter. But the crimes are the least important thing about the book and film, and this is not the cheap and unsatisfying narrative trick that it seems at first glance. The point is that reality has disappeared and been replaced by signs and representations, and that Bateman seems invisible- when reality disappears, man ultimately disappears too, but not in an apocalyptic bang.

When nothing is real, nothing can be fake. In the age of 21st century capitalism, we used to consume with an emphasis on lifestyle and the body as consumer object in order to signal status and self-identity. In what came after this capitalism, this yet-to-be-defined age we are living in, we no longer really need to consume in the classical trade sense to signal self-identity, but the well-memorized and curated simulations of the image and virtues of ourselves will do as upgraded currencies. “Pics or it didn’t happen” or “It didn’t happen if you don’t post it” are expressions of an outdated and misleading critical perspective. It should say, “It didn’t happen once after you pictured / posted it.”

When nothing is real, nothing can be fake, at the same time all is real. We cannot say if Bateman is just simulating to be a murdering psychopath, because there is no reality that serves as a reference, everything is a simulation with actions that have no substance. We can only say that Bateman is shaken to the core when others fail to believe him, making him question his own simulation, but not himself: “/…/ coming face-to-face with these truths, there is no catharsis. I gain no deeper knowledge of myself… There has been no reason for me to tell you any of this. This confession meant nothing.” A statement that can be considered the essence of every single social media post, regardless of its nature.

Two American presidents are featured in American Psycho. The one who is briefly mentioned is Ronald Reagan, whose TV newscast appearance on the Iran-Contra Affair triggers Bateman to conclude „Inside doesn’t matter“ when his colleague speculates about how Reagan must feel inside after having lied in the affair. The other extensively featured is future president Donald Trump, who capitalizes on Reagan’s slogan Make America Great Again since 2016. Here, still in his function as real-estate mogul and celebrity, he serves as mythical figure and glowing idol of Patrick Bateman: Trump is the person he idolizes above all others and tries to emulate, with a copy of The Art of The Deal gracing his desk. The materially wealthy but culturally bankrupt Bateman is actually modeled after Trump: a ridiculously vain, envious and petty show-off who is obsessed with what other people think, one who gets away with everything.

Like Ellis’ American psycho is not only Bateman, but the entire society that surrounds him, hyperreality and simulation is an unescapable state of affairs, even more so 30 years after the novel was penned. Baudrillard’s definition of hyperreality is not a warning, nothing we can distance ourselves from, or moreover use in clever doses. The simulation is too advanced and collective in order to reverse it, or to say it with the final words of the novel, “This is not an exit.”

In his book The Intelligence of Evil, Jean Baudrillard lays out what he calls the “definitive duality” of all things as inscribed into the divine concept of heaven and hell. There is no good without enabling the evil and vice versa (When Mephisto was asked by Faust, “Well now, who are you then?” he gave the famous answer, “I am part of that force which eternally wills evil and always produces the good”). There cannot be a quest for freedom without enabling oppression, more tolerance inevitably leads to more intolerance, more information means more disinformation, more health gives birth to the virus, and so on. Regarding the American Dream there can be only one conclusion: there can be no dream without a nightmare

by Saliha Enzenauer

Thanks for turning me on to Jean Baudrillard, it’s brilliant stuff! Did you know that he turned down working on the Matrix films?

Interesting theory. Bret Easton Ellis is spending his days trolling liberals lately. Maybe you can hire him, because he only wrote American Psycho in order become a music writer. He actually loved the shitty music he was talking about, Phil Collins, Whitney… He meant it.

Amazing analysis of a film that I have long enjoyed but had not understood as deeply as your article. Because the film is the perfect sum of our times. The…how did you say it? “banality” that is all around us. When simulation is better than reality and individuals chosen to in the hyper-reality that Baudrillard talks about. I remember you mentioning the “post-capitalist” society. At the time, I wasn’t sure I agreed the capitalism had been replaced. But now it’s clear we have seen the creation of something new. A move beyond the materialism. All is now a simulation as your article explains so well. Baudrillard may be the most difficult and rewarding thinkers we have. Truly explaining the dystopian world that has been created, a world that we voluntarily surrender our souls too. The modern world that has moved beyond their promise of materialism. You have had my head spinning as I move down this line of thinking. Oh… also want to mention that I’m grateful for your exposing this “red pill/blue pill” talk for the nonsense that it is.

Awesome article. Got my brain in a serious twist.

Please write a full article about Matrix!!! I HATE IT!!!

Saliha,

Your analysis of Baudrillard, capitalism, consumerism, Reagan, social media, and Trump is timely. Trump proclaimed while running for president in 2016 that he could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and he wouldn’t lose voters. The American Dream has always had it’s more real shadow of the American Nightmare in its economic exploitation and endless war.

A great read. Never heard of hyper-reality, a fascinating theory that I must study further. It sure relates to Nietzsche and his predictions about the decline of man in Thus Spoke Zarathustra. Despite his pleasures and comfort, the last man is stagnant, empty, miserable.

Saliha,

This is a priceless article, what an amazing multilayered analysis of Patrick Bateman’s world. This is one of my favorite films, I’ve been searching for ideas on how to extended my original review, and now comes this .. excellent job !.

I’ve always said it: if anything wants to become a masterpiece, it must surpass the TEST OF TIME. American Psycho is a difficult film to forget. Patrick Bateman projects us the idea of ”absolute success”. A life in which we have good education, social position, high rank in jobs, money, luxury, perfect physique, beautiful partners, etc. And what better place to develop all that than New York (The capitol of capitalism). But the question is, what’s left after this “success” is achieved? I believe that many people have found their own happiness in Bateman’s fantasies. And they need more…

As you clearly mentioned, when reality is dead, everyone can be whatever they want, when art is dead, everyone can be an artist. We must accept that our system has reached a critical point, where most people see themselves as a Patrick Bateman (with either one or all of his qualities).

Patrick’s image of himself contrasts with what he really is. He claims to be a deep music lover, but his affection for Whitney Houston and Phil Collins says everything. He claims to be a successful stockbroker, but we never see him work. He claims to be extremely cult, but his conversations feel pretentious and forced. He claims to be a brilliant serial killer, but his methods are pretty obvious. If you think about it for a moment, most people behave like him!.

This is my favorite performance of Christian Bale, his character is highly developed and fiercely performed. There are memorable sequences that leave their own mark on our minds, that’s the case of the business card scene, the shower scene, the Huey Lewis & The News scene, the Whitney Houston monologue, the Sussudio scene, the conversation with the detective (Willem Dafoe), etc.

Bret Easton Ellis novel is also brilliant.

This article is destined to surpass the test of time, VW is something else!

Fascinating interpretation. You made me want to revisit the movie asap.

You’re a favorite writer and the ultimate source for me.

This is a horribly interesting, brilliant article (and video). Just wow.

Outstanding article. I’m surprised and scared at the same time.