Vincent Gallo’s The Brown Bunny (2003): Who Breaks a Butterfly Upon a Wheel?

Some might be surprised that my prime connection to Vincent Gallo is not established via his films, but through his music- since many don’t even know that this man makes music. Gallo’s 2001 album When is in my all-time Top 10, one of the records I always come back to. A very special, intimate and beautifully naïve record with vintage production and irresistibly vulnerable vocals that resemble Chet Baker; a bedroom recording with darkness lurking under its saccharine surface. Similar to Love’s Forever Changes, the record is nuclear L.A. with its underlying malevolence, hinting at that things are just plain wrong and broken- When is a timeless masterpiece.

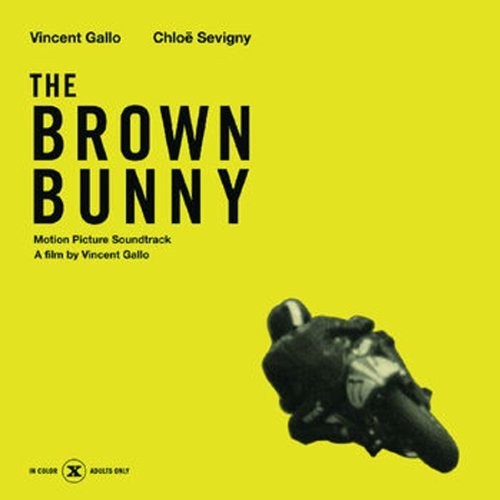

When Gallo’s second feature film The Brown Bunny premiered in 2003, I didn’t watch it until just recently, not just because the reviews were unisono staggeringly bad, but all talk about the film was about an ominous blowjob that Chloë Sevigny gave to Gallo in the film. There was so much talk about the authenticity of that blowjob and the size of Gallo’s cock and narcism, that it was utterly annoying and gave the impression that fellatio cloaked as art is at the center of the film, and so I passed on what I thought must surely be a work of pretentious eccentricity without a cause. It was not until the recent limited vinyl re-issue of the Brown Bunny OST, compiled of songs used in the film and John Frusciante tracks inspired by the film, that I decided to watch the film 18 years after its release. What can I say- I can now imagine how brain-breaking the entire controversy around the film must have been for Gallo himself, because The Brown Bunny is a completely different film than the critical discourse would make you believe. The film is not merely misunderstood, but, astonishingly, the complex topics at its center are not being discussed at all.

The Brown Bunny picks up from where When‘s cover of the American road and the faded technicolor rainbow have left us. Gallo’s very own Americana of highways and desert roads is embedded in gorgeous vintage cinematography that’s 70s inspired but yet more timeless; and built around the character of Bud Clay, a motorcycle racer who is driving from New Hampshire to California for his next race. Throughout his somnambule rite of passage, ghostly and surreal encounters with the past merge with flashes of real memory. In long road shots, the introspective of a lethargic and broken man unfolds during extended scenes of solitude and very sparse dialogue, and it is not until the very last, infamous scenes until this man’s devastating story reveals itself to the viewer.

On the road, painfully gorgeous scenes like the one where Bud races his golden-white #77 motorcycle in the vast salt flats in Utah, desertously blurring and fragmenting with the horizon, make for true magic. Road songs like Gordon Lightfoot’s “Beautiful” and the impeccable Jackson C. Frank’s “Milk and Honey“ (which Gallo completely makes his own) unfold in full broken glory, and Bud’s memorable encounters with three women leave behind a spectral melancholy that resonates for days with the viewer. But none of these flower-named women can replace the one flower that haunts Bud’s memories: Daisy (Chloë Sevigny), his lost love.

Bud’s arrival in a hotel-room in L.A. is the onset to the decontextualized blowjob that ruined the film for me back then. But before I talk about its context, let’s get over the cock-sucking quickly: it is obviously real, pornographic and therefore uncomfortable to watch. Gallo shows his huge erection that must be the source of the narcissism allegations against him. Not only is it puzzling that critics would object to all actors inherent narcism by expanding its definition ideologically and do so in the realms of modern & experimental art, but I perceived Gallo to act with shyness and vulnerability throughout the entire film. Although he plays the sole lead role in a film that he wrote and directed, the close-ups cut off half of his face more often than not and Gallo’s manic swagger from his debut Buffalo 66 is toned down, as is his impeccable sense for fashion that was on full display on that film.

The hotel-room scene is an intimate chamber play; otherworldly through Daisy’s ghostly mild appearance and authentic in Bud’s emotional turmoil and resistance that’s expressed in violently restrained whispers. What begins like the reunion of a separated couple and the cathartic accusations of a horned man directed at his cheating and wrong-doing lover, turns into an epic of unfathomable depths, a story in which it is revealed that Daisy got raped and is dead, her appearance nothing but a thorned illusion of Bud’s torments and sufferings.

What do you do when your pregnant girlfriend, your love, your bunny, your daisy… gets raped, and right in front of your eyes? In the kindergarten-level moral specter of Hollywood, the answer is easy: you turn into a hero that rescues her from the predators, preferably by combing the place with bullets, then you lick her wounds selflessly in between lots of crying together, you heal her with your love and strength. But such scenarios have always been over the rainbow due to the reality of the much more complex and nuanced natures of human nature and guilt. A visibly more immature Bud in a blue tracksuit top is paralyzed when he witnesses the rape of his passed-out girlfriend during a party, he is paralyzed when he sees one man penetrating the vagina and another the mouth of her unconscious body while a third man is waiting for his turn; and runs away from his personal paradise lost.

It’s not just questions about his cowardice and guilt that multiplies to inconsolable ends because Daisy dies that night which haunt Bud endlessly. Or questions about Daisy’s guilt, who did drugs with strangers while being pregnant and was then raped by these same strangers. What if you can’t help but feel numbing jealousy and shame as a visceral reaction to the images haunting you? What if you are overwhelmed by a selfish grief and despise that you were put into this situation and condemned to misery? Because what happened to Daisy, also happened to Bud differently: a moment breaking into the couple’s eden, destroying love and hope for good. Gallo leaves the beaten paths of highly consensualized formulas of emotion and reaction and is more close to the realms of the grand literary narratives with their complex heros when he deals with these messy and authentic depths, and amazingly, he manages to do so cohesively in a highly experimental narrative with very little dialogue. And yes, in the context of the overall storyline, the blowjob scene ultimately turns out to be strangely compelling, inevitable even, as it revives the rape and lays bare human emotion beyond a field of fast morals and ideologies.

It’s hard to understand why critics collectively overlooked these aspects in what is undoubtedly the movie’s most exposed and important scene- and it makes you indeed question that profession which is not disintegrating into oblivion for no reason since a few years. Almost two decades after the release of The Brown Bunny, realization should settle in that America is not rich on daring directors like Gallo, who never received the credit that he deserves in midst such a bleak cinematic landscape. The damage done might be greater than we think- Gallo has done just one other feature film since The Brown Bunny, but he won’t release Promises Written in Water because he wants it stored “without being exposed to the dark energies from the public,” and further, “I do not want my new works to be generated in a market or audience of any kind.” Who breaks a butterfly upon a wheel?

Truth is that The Brown Bunny is a devastating and devastatingly beautiful film, a brave, accomplished work by Gallo who retrieves beauty in unexpected waters that are the opposite of grandezza: messiness, amateurishness, authenticity. Watch alone.

by Saliha Enzenauer