Türküola & Co: The hidden history of Turkish independent labels in Germany from the 1960s to the 1980s

The first, largest and commercially most successful independent record company in whole Germany until today has been Türküola. It was founded in Cologne by the Turkish migrant Yılmaz Asöcal in 1964. In the history of independent record companies as well as in the history of pop music in Germany Türküola and the many other Turkish independent labels in Germany are not mentioned, the companies and their history remain hidden. Why remain these labels hidden in music historiography until today, and what is so special about them? And why did the Turkish labels in Germany have no access to the German record industry’s relevant official promotion and distribution channels (hit charts, media, stores)? Having no access, the labels had to invent their own promotion and distribution channels. What helped them to succeed was the Turkish attitude and practice of DIY and “going independent”. This attitude and where it derives from will be in the focus in this essay.

Independent labels in general

In the beginning of the vinyl record era in the 1950s, a so-called major-label controlled production, manufacturing and distribution. If a vinyl record label did not control this process entirely, it was recognized as an independent label. In the 1960s, the notion of highly successful charts music started to be the main idea of major-labels, while labels selling less were more on the side of independent labels. But in general, major-labels and independent labels were not in opposition: independent labels used the access to the market, especially the established promotion and distribution channels of the much larger multinational major labels. However, the term “independent” points to a legal and, to a large extent, economic independence from the major media corporations. According to Charlie Gillett, one key criterion for separating major- and independent labels is the access to the market via promotion and distribution channels. Owning one or several such channels could make you a major label.

Music-wise, the economic pressure for musicians associated with independent labels, especially with artist-run ones, could encourage experimentation and creative autonomy in music making. With major labels, however, music making is much more commercially driven, usually within a smaller, conservative range of aesthetic possibilities. To be clear: For majors, the musical material is completely unimportant as long as profit can be made from it, whereas independent labels care about their music and their – often minoritarian – audiences, which they also represent.

Yet, the separation between major and independent labels is still an artificial one, as an in-between construction (so-called “major-independent labels”) also exists, depending on access and ownership of promotion and distribution channels. This point will be relevant in the course of this article. Since the late 1970s, the idea of independent labels is generally closely connected to punk music and its DIY-spirit, enabling music production, promotion and distribution alongside the established major-owned channels. Here, my subject, the Turkish (major-)independent labels in Germany, leads me to re-think this idea: There has been a great portion of DIY-spirit and non-hegemonic underground practice within Turkish (major-)independent labels more than ten years earlier than punk broke. To a certain extent, the Turkish (major-)independent labels in Germany developed a prototype for punk music’s independent label thinking – without punk music ever knowing and referring to this prototype. The Turkish (major-)in- dependent labels had to keep their model of “going independent” underground or were deliberately kept out of sight – we will come back to this issue.

Starting with the so-called ‘guest workers’ in the early 1960s, the largest Turkish migrant community outside of Turkey built up in Germany, growing up to over three million people today. Yet, representation and acknowledgement of this community in the cultural life of the German society has been and still is weak, and when it comes to Turkish record labels in Germany, they are almost totally neglected. In 2020, Christopher Ramm summed up the state of research on Turkish pop music in general: “It is striking how little attention academic research gave to Turkish pop and rock music of the 1960s and 1970s until very recently,” and he detected a general “lack of interest.” This has changed significantly since about 2018, not least with a new wave of Turkish scholar publications in English. Yet the current research did not go far enough to bring up a deeper understanding of the Turkish music market in general and especially of the Turkish music market in Germany. The history of migrant music culture that had emerged in Germany since the mid of the 1960s is in general almost completely absent from public perception. The literature published to date is very limited and archives are lacking. The music and culture of migrants has apparently not yet been considered relevant enough to be documented, archived and protected. After about 60 years of Turkish music made and produced in Germany, there still exists no comprehensive history of Turkish music in and from Germany, let alone a history of its music labels. A fact that has to be researched, questioned and discussed. To do so, I propose to analyze the discourse (or the lack of it) about these labels and the music and people linked to them, in order to understand why these independent labels have been blocked from the official distribution channels, and why they are written out of cultural and music history until today.

Journalist Adama Juldeh Munu states about hidden histories: “It suffices to say ‘hidden histories’ are either due to willful design to keep them hidden or the lack of reliable sources that makes proper enquiry possible.” In our case both takes place. Since Martin Stokes’ observations in 2010 things have not really changed: “The topic [of the Turkish music market] has been neglected, and facts and figures are hard to come by.” A reason for figures being hard to come by are various interest groups manipulating them upwards or downwards. Therefore, non-transparency starts already within the Turkish music market itself. Yet, larger structures are at stake in Germany. Researcher Vanessa E. Thompson observes: “In Germany, there is a systematic failure to recognize racism as a structural and institutional problem.” One element of racism as a structural and institutional problem is to push out or ignore the history of Turkish music made in Germany from the historiography of music in Germany. And things go deeper: the willful design to keep a certain history hidden has to do with a basic structure of ‘access denied’ when we ask for the reasons for the hidden life of Turkish music in Germany. The independent Turkish labels in Germany and their special distribution system were made up specifically because of an experienced ‘access denied’ to the existing structures for musical life. And this attitude of ‘access denied’ just turns up again when it comes to the historiography of German music. This is what Thompson means: there is “a systematic failure to recognize racism as a structural and institutional problem”. What are the reasons for this ‘access denied’ and which larger willful design shapes it?

‘Access denied’ – Racism and Turkish independent labels in Germany

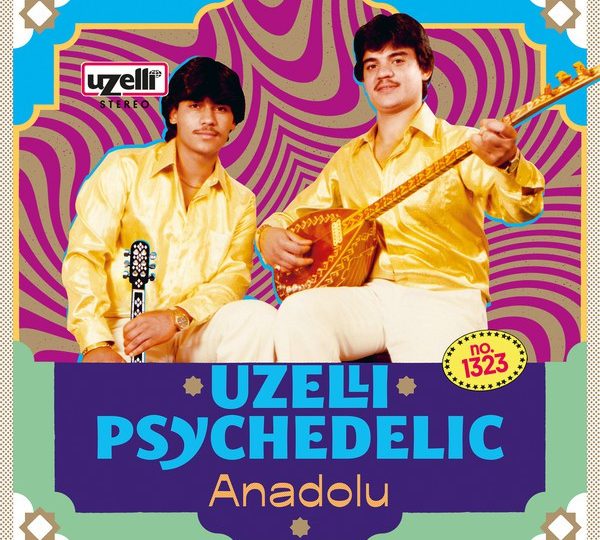

The first German independent labels to be acknowledged in the history of the German record industry is usually David Volksmund Produktion (founded in 1971 by the music group Ton Steine Scherben) or Trikont (founded in 1972) – but this is not true. In fact, the first, largest and commercially most successful independent record company ever in Germany has been Türküola. Türküola, founded in 1964, released more than a thousand singles, albums and compilations by Turkish artists. The recordings were made in Turkey and Germany primarily for the Turkish community in Germany as well as in Europe, but also for the export to Turkey. The company sold millions of records, CDs and cassettes, in Germany, Europe and Turkey, winning golden and platinum records. And Türküola was only one of a much greater number of (major-)independent Turkish record companies in Germany like f.e. Minareci (founded in 1969 in Munich) and Uzelli (founded in 1971 in Frankfurt). Though the first record released by a Turkish-German record label is not easy to track down, it was probably Metin Türköz with “Almanya’da Neler Var/Altmışlık Oma” released in 1965, or one of the other early Metin Türköz records released on Türküola’s sub-label Türkofon.

There were a lot of independent record labels founded, smaller and larger ones, with infrastructural backing by Turkish studios which existed in many European cities. Greve lists about two dozen independent Turkish record labels in Germany, about seven of them being major-independents, one of them representing also up to 180 Turkish companies for the German and respectively the European market. Of course, over time, these labels did not sell only vinyl records. Vinyl faded out in the 1980s, instead cassettes, starting around the mid 1970s, and CDs, starting from the 1980s, came into the shelves. We still have no clear picture of the Turkish music market and its volume in Germany, but outlines of an extraordinary and powerful release and distribution system can already be detected. And if we consider the Turkish labels from Germany selling also to Europe and Turkey, like Türküola did, one can start to believe the circulating anecdote of sacks of cash being dropped each evening in the central Türküola store in Cologne. As these labels had no access to the German record industry’s relevant official promotion and distribution channels (hit charts, media, stores) they had to invent their own promotion and distribution channels, primarily with grocery stores and general stores as main selling points and Turkish newspapers as media displays. With his sub-label Teledisc, founded in 1968, Asöcal even tried several times to enter the German record industry’s system. However, this sub-label has been a failure with only half a dozen releases including German schlager and English versions of Anadolu rock songs. Asöcal gave it up in 1980.

Why did Turkish labels experience an ‘access denied’ when it comes to the German record industry’s relevant official promotion and distribution channels? We have to come back to our observation concerning structural racism. Which structure profits, one may ask? A structure that is built on cheap labor forces and which needs a justification for the ultra-low and un-equal payment. Is there a better one than people being of little value, their cultural identity, including their music, being of little or no value? The logic of racism is a logic of devaluation – and profit. In her documentary film Yeryüzü Göçerleri (1979), Gülseven Güven openly compares and parallels migrant Turkish people with black people as slaves. The film even presents Turkish migrants as slaves within a slave trade organized by the Turkish state, who sells the folk as labor force to work abroad for sending in valuable foreign currency, which the state needs desperately to compensate the immense trade deficit. The status of Turkish migrants in the social hierarchy in German society was made clear in the film: “They are at the end of the list,” as the narrator puts it toward the end of the film. And in fact, Turkish people have been named colloquially often “the N*****s of Europe,” to maximize their othering and devaluation. Thomas Solomon sums up the status of Turkish people by describing them as “second-class non-citizens in Germany.” Here a willful design comes in again, a willful design which one may relate to Boaventura de Sousa Santos theory of “abyssal thinking” turned into an abyssal practice of exclusion and denial.

Being structurally and socially marginalized, it is maybe no wonder that ‘access denied’ is one of the basic experiences for Turkish people in many regards. They could not enter many cultural, educational and recreational facilities, their life was reigned by a more or less unspoken separationist racism and classism. Although Germany being a capitalist society, the potential money Turkish people could bring in to cultural, educational and recreational facilities was not welcome. Doors were closed to them even as consumers or clients, because they were regarded as a disturbance and devaluation for the consumption process for and by many other people in Germany. Racist and classist thinking overshadowed dominant commercial interests. This might also explain the almost complete absence of Turkish products, music, film and culture in public life, be it in German media (television, radio, newspaper), in stores (also music stores) or in any cultural venue (cinema as well as art and design museums etc.).

Going against this situation and to survive culturally, Turkish people had to establish independent structures for their everyday life, including their musical life. They had to think outside of the box and use go independent. Starting at first with halal butcher shops, other food like bread, pastries, and cheese as well as objects of everyday Turkish life that were made available for Turkish people by the many independent Turkish grocery and general stores all over Germany. They did and still do not belong to any of the big German food chains which took over the market over time. So, out of a basic need for musical life Turkish people did the same for music as for food and everyday objects, namely building up an independent structure for the promotion and distribution of their music, most often connected to the already existing independent grocery and general stores. Because of this independency, non-Turkish people living their lives in Germany without ever using Turkish shops could not notice much of Turkish music and life. This led to a structure of co-existence without many points of contact. Musical activist Sebastian Reier observed: “Millions of Turkish sound media are sold in the Federal Republic of Germany from the late sixties on. There are no reviews in [German] music magazines, nor are there any pop-cultural considerations in the feature pages. The star cuts in Bravo [the popular German music magazine] are reserved for Western pop stars, and supra-regional television appearances by Turkish musicians can be counted on two hands. Companies like Türküola are also not taken into account when determining the charts. Turkish music remains in its parallel universe; very few Germans come into contact with it.”

The earliest notion in German press concerning the hiddenness of Turkish music in Germany was probably made in 1995 by Daniel Bax. Due to him, the fact that Turkish music has not been successful among non-Turkish people in Germany had less to do with aesthetic reasons than with structural ones: “Turkish music appears almost exclusively on domestic labels, and production is nationally limited. Although large quantities of Turkish CDs are pressed for the European market in southern Germany, at the Destan Müzik company in Esslingen, for example, they are sold exclusively in local Turkish stores. There, as a rule a CD costs no more than 10 Marks. But neither large music department stores like WOM nor special stores subscribing to world music like Canzone at Berlin’s Savignyplatz list them.”

The hiddenness of Turkish music in the public mind in Germany could indicate, coming back to Adama Juldeh Munu, either the lack of a relevant body of music, the lack of knowledge about an existing body of music, or the lack of a will to deal with an existing and known body of music. The situation is undoubtedly complex, as indicated by the fact alone that Türküola was only one of a greater number of Turkish record companies in Germany. More than 20 newly founded record companies in the 1970s and 1980s existed next to Türküola. So, a relevant body of music in terms of quantity and success could not have been the problem. Yet, could this body existed without non-Turkish people in Germany knowing anything about it, because Turkish music in Germany had been rendered invisible and inaudible: due to German media structures, due to Turkish and non-Turkish people living in a more or less distant co-existence, and due to a combination of ignorance and lack of interest in any kind of Turkish music on the side of non-Turkish people.

The history of ‘going independent’ as attitude

‘Going independent’ as a Turkish tradition and attitude in dealing with media and markets has been developed in three main systems, which are partly interconnected: the ‘bond system’ of Yeşilçam cinema in Turkey, starting at the end of the 1950s, the ‘İMÇ system’ of independent Turkish vinyl record labels, starting in the early 1960s, and the ‘co-shop system’ in Germany and throughout Europe for independent video cassette and music distribution of independent labels, expanding in the early 1980s.

The ‘bond system’ of Yeşilçam cinema

In short, this unique system worked between 1960 to 1980 as follows: “Theatre owners in Turkey in the 1960s pre-sold the tickets and then financed the making of the films.” Due to a lack of capital on side of the producers, the Turkish film industry invented an independent system of film-financing and film producing. Akser and Durak-Akser explain it:

“The financial investment originated from an advance on receipts system, which depended on Anatolian theatre owners. Indeed, the so-called ‘Bond System’ was named after the bonds signed by the producers, who borrowed money from the theatre owners by pre-selling the screening rights of the films. In return, the theatre owners could dictate what kind of films were made and which star should be assigned to a particular project.“

The roots of this system date back to the 1940s, when the Turkish government prohibited the import of popular Egyptian films (to prevent the Turkish people from becoming ‘Arabic’) and set up a decree on taxation that reduced the tax on Turkish films significantly compared to the tax on foreign films. This led to the establishment of a profitable domestic film industry at the end of the 1940s. Filmmaker Halit Refiğ reflects on this system, its special economic mode of production and its independency already in 1968: “Since Turkish cinema was not founded by foreign capital, it is not the cinema of imperialism, nor is it the cinema of the bourgeoisie, since it was not founded by national capital, nor was it the cinema of the state, since it was not founded by the government. Turkish cinema is a ‘people’s cinema’ since it is based on labour rather than capital and was born out of Turkish people’s need in films.” He concludes two years later, pointing to the fact that Turkish cinema depends solely on the audience: “This bond system […] was based on the agreement that a film’s expenses would be reimbursed only after the film was made and the tickets sold. As the real bond owners were the audiences, these films were supposed to be made according to the taste of the Turkish audience.” And in another text, he notes: “Today [in 1967], what makes the production of more than 250 movies a year in Turkey possible is not the presence of a certain capital but the bonds calculated according to the number of people who will pay to watch the film. From this perspective, Turkish cinema is a cinema of the people.“

The ‘bond system’ of the Yeşilçam cinema allowed for a worldwide unique independent economic, production and distribution mode. Looking back from today, one could name it a sort of crowdfunding avant la lettre. It served as a model and pathed the way for building up in parallel an independent music market in Turkey and Germany with many independent music labels

The ‘İMÇ system’ of independent Turkish vinyl record labels

As early as around 1900, 78rpm shellac records entered the Ottoman empire. The field was dominated almost exclusively by multinational, European-based record companies like Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft, Lindström, Odeon, Beka, Lyrofon, Favorite, Grammophone Co/His Master’s Voice, Columbia, Pathé and many more. They produced records of Ottoman music but also of Eastern and Western music and hybrid entertainment music styles for the Turkish music market. Turkish record labels did not show up until the end of the 1950s when 45rpm technology became available. The Turkish label Grafson, founded in 1958, started in 1959 with releasing vinyl 45rpm records by the openly non-binary superstar Zeki Müren.

Following its opening in 1960, the huge modern architecture block of the İstanbul Mani-faturacılar Çarşısı at Unkapanı was becoming the center of the Turkish vinyl record industry and its record labels. With the record releases of the famous Altın Mikrofon [Golden Microphone] song contest from 1965 on, numerous local, often musician-owned Turkish record labels began to flourish and “were providing an avenue of creative expression,” something which the global major corporations probably could not have provided the same way.

There is something special about the Turkish music market compared to other countries taking part in the worldwide first wave of hybrid pop music, which combines global with local pop music elements. The Turkish music market was an almost completely independent one with some more important major-independent companies, but also a substantial number of smaller independent players releasing music to a highly dynamic market. The main reason for multinational major-labels to be cautious, back out or stay away from the Turkish music market have been problems with a constantly unclear legal copyright situation, which put licensing and local pressing in Turkey into question, as well as high import taxes on foreign goods which made imported foreign records expensive. The infrastructural backbones for Turkish pop music have been domestic recording studios as well as domestic pressing plants, of which two had been working in 1963 and already eleven in 1969. Ali C. Gedik sums it up: “[…] the introduction of 45rpm manufacturing techno-logy in the 1960s […] enabled a domestic music industry and massive local consumption of music for the first time.”

The effects on the development of Turkish pop music were tremendous. Being independent from the multinational major-labels provided the above mentioned “avenue of creative expression,” with music made according to the imagination, taste and need of the musicians and the audiences. The magnitude, diversity and variety of hybrid pop music styles and sub-styles in Turkey, which grew dynamically from the 1960s until the military coup in 1980, is probably unique compared to other non-Western countries of the same period. Perhaps no other non-Western country – except for Brazil – can offer such a creative pop music development based on an independent music market. Martin Greve writes about “an avalanche-like opening of the market: in 1966 there were 20-30 record companies in Turkey, in 1987 there were 120, and in 1995 there were almost 500.” Many of them were – and some still are – located in the İMÇ building, a symbol of the density and richness of the Turkish record industry. The ‘İMÇ system’ stands for a highly dense, interconnected and powerful independent music market in Turkey. So, with Turkish people migrating to Germany from 1961 on, it was no wonder that they brought with them their attitude of ‘going independent’ based on their experiences of the Yeşilçam cinema ‘bond system’ and the ‘İMÇ system’ of independent Turkish vinyl record labels. One of these people was Yılmaz Asöcal, the founder of Türküola.

The ‘co-shop system’ for independent distribution of Turkish independent labels in Germany

As the Turkish-German record labels had no access to the German record industry’s relevant official promotion and distribution channels and media, they teamed up with grocery stores and general stores as main selling points in a sort of co-shop system and with Turkish newspapers as media displays. Only a few stand-alone Turkish record shops existed in some larger German cities like Cologne, Munich or Berlin, yet over time about up to 400 co-shops existed all over Germany.

The development of independent Turkish record labels based in Germany needs to be seen in connection to another medium: film. At first film on celluloid, then film on video cassettes. Of course, Turkish films received the usual ‘access denied’ for regular programming and screening in all German cinemas. But as early as the 1960s, the idea of taking over German cinemas temporarily evolved from the Turkish attitude of ‘going independent’ combined with mercantile agility. Some enterprising film people had the idea of renting the existing train station cinemas for a certain time frame in order to show Turkish films to a Turkish audience. The cinemas and the cinema halls were mostly rented completely on weekends for early screenings, and their own Turkish people were also placed as workers at the box office. So, without owning a cinema infrastructure, Turkish films could were to a Turkish audience in Germany.

The whole game changed significantly with film on video cassettes. Video became a mass medium in Germany by the end of the 1970s. After a research conducted in 1982, there have been already twelve big Turkish manufacturing companies and another twenty smaller video labels in business at the time, and the trend was upward, like mushrooming. Towards the end of the 1980s, around a hundred branches in Berlin alone sold video cassettes. A lot of these branches were not stand-alone video rental stores, but co-shops, registered under other branches like travel agency, hairdresser, bank, and rag shop. These shops had marked sections for video rental and sale as well as point of sales for music, both often as a complement to the particular assortment. In general, all kinds of Turkish shops in Germany very often had a video and a music section. Some of the labels even released both video and music, like the major-independent Destan Müzik from Esslingen, which produced and distributed video cassettes as well as music cassettes and CDs. In the co-shops, several things came together: food, objects for everyday life, Turkish press, Turkish film and music media, and Turkish musical life like concert promotion and ticketing. This kind of independent distribution for Turkish film and music media was unique to Germany, no other group of migrants had established something comparable – and they did not have to do so: Italian, Greek, Portuguese, Spanish etc. films and music had no ‘access denied’ on the doors of the official promotion and distribution channels.

So, born out of exclusion and necessity, under racism as a structural and institutional problem, Turkish and German-Turkish musicians, which would never be signed by a German or international record company for the German market, called for Turkish independent record labels and independent promotion and distribution channels, and are today republished by hip labels specializing on international music, like Mr. Bongo or Pharaway Sounds. They evolved together with the first wave of Turkish labor migrants in the 1960s – about a decade earlier than German music history tells us when it comes to the establishment of independent record labels in Germany. Yet, here we have not only to correct German music historiography but also the mindset which goes along with it. A mindset which should finally face racism as a structural and institutional problem.

by Holger Lund