The Radical Blackness of Digable Planets

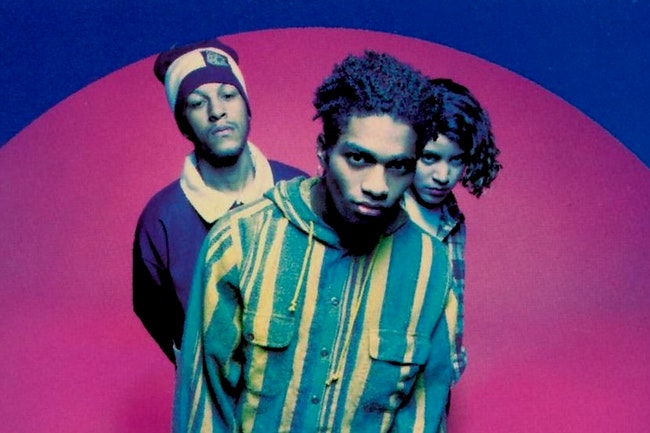

The story of Digable Planets begins during the late 1980’s in the culturally rich City of Brotherly Love. Ishmael ‘Butterfly’ Butler was based in Seattle, interning at Arthur Russell’s Sleeping Bag Records in New York, and intermittently visiting his grandmother and father in Philadelphia. Meanwhile, studying at the prestigious HBCU Howard University in Philadelphia, Craig ‘Doodlebug’ Irving got into the local hip hop scene through hanging out with some Five-Percenters, where he’d often see and talk to Butler. Here, Irving also met Mary Ann ‘Ladybug’ Vieira, a Brazilian-American dance-crew member from Maryland, introducing her to Butler. Eventually, Butler would recruit both Irving and Vieira for his project, named Digable Planets, signing with Pendulum Records off of the strength of a few loose demos.

It’s this collision of incredibly different artistic identities and backgrounds that made Digable Planets such a unique, vital voice in the burgeoning East Coast hip-hop scene of the early ‘90’s. Along with contemporaries like De La Soul and A Tribe Called Quest, Digable Planets became forebearers of a new, peacefully afrocentric sound that stood in stark contrast to the gangster rap sweeping the West Coast scene. Sharing interest in Five-Percenter ideologies and the teachings of Marx, Sartre, and Nietzsche, the trio’s lyrics combined down-to-earth observations of their inner-city surroundings with their utopian philosophies.

Then of course, there’s their sound itself, a vibrant, effervescent hybrid that, in looking back into the canon of black music from Art Blakey to James Brown, radiates an undeniable blackness in every note, a marvelous brew of funk, jazz, and everything in between. However, the synthesis of this sound wasn’t as intentional as one may expect. As Butler said in an interview with Pitchfork, “I was just using the samples that I could get my hands on; they were from records that belonged to my moms, my pops, and my uncles.” Taking in the avant-garde and Motown jazz his parents liked, and combining it with the music of artists like DJ Premier and Prince Paul he was listening to, Butler found an accidentally perfect equilibrium between crisp beats and ingenious samples.

These elements all come to a head on Digable Planets’ debut on Pendulum/Elektra, 1993’s Reachin’ (A New Refutation of Time & Space). Titled after a time-invalidating essay by Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borge, the album is an effervescent, colorful work that radiates positivity and harmony, the trio working in perfect balance. There’s the vibrant opener, “It’s Good To Be Here”, where percolating percussion, soft guitar, and freeform horns adorn the trio’s smooth flows. On “Pacifics”, the three tag in and out of the minimal, Lonnie Liston-sampling beat, complete with a slick bass-line and a sax loop. The blown out saxophone that carries “What Cool Breezes Do” is a bold pop of sound, juxtaposing nicely with the spacey, phased-out beat. “La Femme Fetal” is a biting criticism of pro-lifers and, in a greater sense, patriarchal, authoritarian fascists, accompanied by a skronking, modal sax line that gives the song a slam-poetry feel. The saddest part is, the song’s as relevant to a nation that’s currently fighting as hard as it can to alienate and strip women of their rights as it was 25 years ago.

The Art Blakey bass-line that builds “Rebirth Of Slick (Cool Like Dat)” is instantly recognizable, as are the fantastic horns that adorn the hook. With each member taking a verse, the most memorable is Ladybug’s, her assured, laid-back delivery practically gliding over the drums. It seems like Butterfly knows it too, closing Ladybug’s incredible verse with an awestruck ad-lib comparing her to Cleopatra Jones. “Rebirth Of Slick” became a huge hit, reaching #15 on the Hot 100 and boosting the sales of the record. It’s the reason Digable Planets have a Grammy to their name, for Best Rap Performance by A Duo/Group, having won in 1994 over the likes of Snoop Dogg & Dr. Dre.

Even as “Rebirth of Slick” is the trio’s most essential song, it’s not the best track on the album. That honor goes to “Where I’m From”. Built on the “Funky Drummer” break from James Brown, what sets the song apart is an amazing KC And The Sunshine Band flip. Taken from the first few seconds of their song “Ain’t Nothing Wrong”, the sample is sunny and joyful, funky licks of guitar joined by bright horns. Doodlebug, Butterfly, and Ladybug each wax poetic on their backgrounds in urban sprawl, loose and playful over the gorgeous beat. It’s thrilling, and I can’t help but smile every time I hear the song. “Where I’m From” is a perfect microcosm of Reachin’, filled with positive vibes and unabashedly black.

The tone on Digable Planets’ 1994 follow-up record, Blowout Comb, is decidedly darker. In a way, Digable Planets’ transition between Reachin’ and Blowout Comb is similar to the artistic maturation of their contemporary De La Soul from 3 Feet High And Rising to De La Soul Is Dead. The same way De La killed off the D.A.I.S.Y. Age platform they had championed on their debut, gone were the bug-related nicknames and imagery. Intended to be a metaphor for the way low-income black communities stick and work together like insects, the message had been convoluted into something unrecognizable to the group, and a change in direction was needed. Butler, formerly Butterfly, became Ish, Vieira, formerly Ladybug, became Mecca, and Irving, formerly Doodlebug, became C-Know.

The group moved from Philadelphia to Brooklyn in 1993, and as a result of their instant connection with the borough, Blowout Comb was intended to be a “Brooklyn album”, a collaborative product born from the rich hip-hop scene thriving in the city of churches. Lyrically, the peace and love of Reachin’ has been replaced with something more intense, heavier allusions to the Black Panther Party and the Nation of Islam, taking a closer look at Brooklyn’s urban surroundings, and doubling down on the afrocentrism. The title extends these afrocentric themes, referring to a comb used primarily for naturally afro-textured hair. The album cover and liner notes are adorned with Black Panthers imagery, even complete with fake ads for soul food.

Inspired by Wu Tang and Black Moon, the group decided to abandon some of the more radio-friendly sounds that made Reachin’ such a hit, aiming for something more daring and minimalistic. Musically, Blowout Comb is nothing short of stunning. The album sounds crisp, hard-hitting, and cozy, radiating a nocturnal atmosphere that evokes a dusky smooth-jazz bar. Vibraphones, horns, and Rhodes keys build the general sonic atmosphere, grounded by knocking percussion and the same fantastic bass-lines that made Reachin’ such a memorable listen. The beats are entrancing, and the sonic environment exists to benefit them; even the vocals are somewhat buried in the mix, wisping about like an air of blunt smoke.

The first thing we hear on the record is the intimidating blare of brass, fanfaring as the background crackles like a dusty record. The toms burst up, and the beat drops, with a smooth, slowed-down Wes Montgomery sample at the helm. This is “The May 4th Movement Starring Doodlebug”, a radical mission statement that shouts out Mumia Abu-Jamal and Sekou Odinga, rails against the government’s efforts to silence blackness (COINTELPRO & black incarceration), and drives the Brooklyn flag into blackened, scorched Earth. It’s one hell of a tone-setter, and the rest of the record keeps the pace. The squelching bass that carries “9th Wonder (Blackitolism)” is awesome, paired with hard-hitting percussion and guest vocals from Jazzy Joyce. “Jettin” takes this amazing Rhodes loop, setting it to a smooth bassline and a knocking boom-bap beat, riding it out for a funky excursion as laid-back as it is fun, one of the lighter songs on the record.

One of the heaviest is an exploration into “Black Ego”. It’s a marvelous expansion of the black nationalism and afrofuturism Digable Planets’ ethos was built upon, more overtly radical than anything they had done before. It begins over a stark Grant Green loop, as a scene from the blaxploitation film Cleopatra Jones plays out, a self-referential call-back to an ad-lib from the song that won Planets a Grammy. In the skit, Butler’s being hassled by a cop. To resist being silence, he waives his Miranda rights, a bold act of righteous defiance. Suddenly, the sample gives out from under the song, leaving some keyboards, then dropping the beat. Viera, Butler, and Irving command their verses with an assured grace, holding on for 7 gripping minutes as Funkadelic samples come and go. “Black Ego” is the sound of transcendence, launching a manifesto birthed from Brooklyn, weed, and radical philosophical musings into the blackness of outer space.

As mentioned before, Digable Planets wanted Blowout Comb to be a record of collaboration that soaked up the vibrancy of early-90’s Brooklyn. Nowhere is that more evident on the final track, the gorgeous “For Corners”. The beat, one of the jazziest and headiest on the record, is marvelous, adorned by an effervescent Roy Ayers horn sample that gives it another layer of funk. The three rappers trade 8-bar verses back and forth, stirring in friends like Sulaiman. Monica Payne shows up, shouting out fellow artists, collaborators, and boroughs. It’s radiant, even without the sound effects of lapping waves, a fitting closer that glows in the light of a setting sun.

Digable Planets broke up in 1995, just 2 years after the release of Reachin’. It made sense, too. Vieira was reeling from the loss of her grandparents, their creative visions had begun to diverge from their major-label attachments, and the grind of the music industry had taken a toll on the relationship the group had with each-other. Their break-up was symptomatic of the gradual end of an era; the conscious jazz-rap era was slowly waning, succeeded by the East Coast hardcore of Biggie and Nas that’d take America by storm. Planets could only last so long in such a quickly shifting environment.

Of course, it hasn’t stopped the group from reuniting, once in 2005, and once in 2015. What’s more, each of the three members has released solo work, most notably Butler’s acclaimed, influential experimental hip-hop duo, Shabazz Palaces. As little music as we got from the trio in their prime, the importance of Digable Planets stretches far past their body of work. They remain one of the most important groups in hip-hop, their singular creative vision and unapologetic blackness still their own, 25 years later.

by Raghav Raj

What a wonderful think piece on these legends.

So damn good. Consider me schooled.

Yes! Digable Planets!! Thanks for this article!

Great piece!! LOVE Digable!!