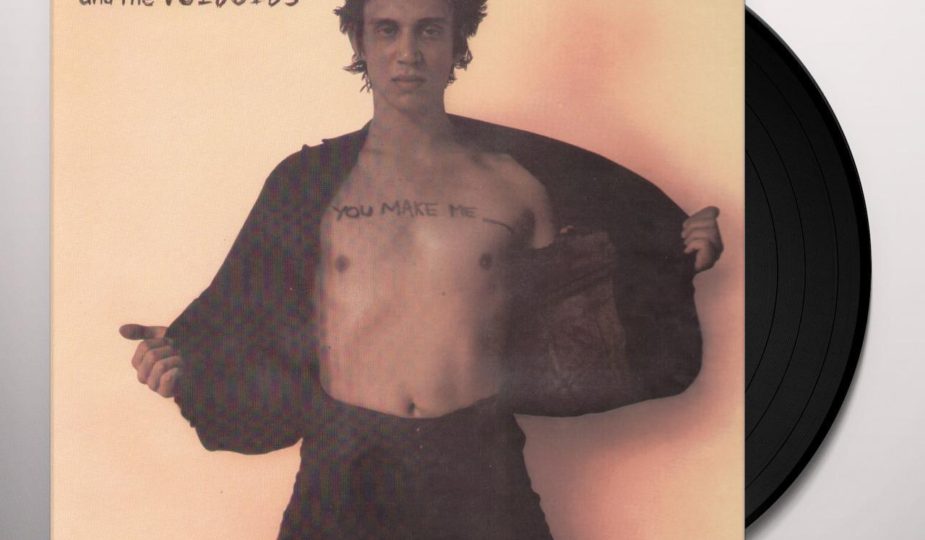

Richard Hell & The Voidoids -Blank Generation (1977)

Few truly embodied the punk ethos like Richard Lester Meyers did. A high school dropout, he and another friend, Tom Miller, moved to a New York City in the early stages of the punk explosion due to happen in the next couple of years, in pursuit of his passion as a poet. Adopting new names after French poetry (Meyers became Hell after a poem by his icon, Arthur Rimbaud, Miller became Verlaine, after the famed symbolist poet), the duo founded a new band called the Neon Boys with drummer Billy Ficca. When Richard Lloyd joined on guitar, Neon Boys became Television, and became mainstays of the fledgeling CBGB marquee.

Hell however, had increasingly grown erratic in his time with Television, his need for creative control leading him to constantly butt heads with Verlaine, who would kick him out of the band in 1975. Hell responded by moving on to a second highly influential group, The Heartbreakers, formed with former members of the New York Dolls, Johnny Thunders and Jerry Nolan. This too, wouldn’t last, as Hell, once again frustrated at being creatively silenced, would part ways with them almost exactly a year after his split with Verlaine in Television.

Determined not to stop or to box himself into a corner, Hell went right at it once again and set off to build a new band. He recruited guitarist Robert Quine, who he had worked in a bookstore with, and found his second guitarist, Ivan Julian, in an ad on The Village Voice. Drummer Marc Bell, known for work with Wayne County, would join later, completing the lineup of what would become The Voidoids. It was with this team of musicians that Hell finally got the creative control he had been thirsting for, and it’s on Blank Generation, The Voidoids magnum opus, that we truly see a restless innovator of punk at his prime.

Instinctually, as I listened to Blank Generation, I found myself comparing it to the equally influential Marquee Moon, the beloved 1976 masterpiece from Hell’s old bandmates at Television (and one of my favorite punk records). Both albums are fundamental documents of the 1970’s New York City punk scene, yet, to compare them is to compare rock candy to meth —surface level assumptions may lead you to think they’re similar, but what they do to you is worlds apart. Upon first listen of Marquee Moon, one thing I immediately noted was how polished it sounded, how tight Billy Ficca’s drums were, how slick the guitar fills of Richard Lloyd were. Blank Generation, on the other hand, throws any semblance of subtlety immediately out the window, Marc Bell’s drums crashing everywhere as Robert Quine’s solos screech, wail, and yelp to no abandon, nothing but unfiltered energy driving each and every song. Where Verlaine’s vocals calmly steer through the soundscapes set by Television, Hell consistently sounds like he’s flooring the gas pedal while shooting chunks of heroin into his veins. Television’s power came from their restraint, and their execution was flawless. It’s easy to see why Hell wasn’t a good fit with Television, as it was raucous spontaneity that Hell and The Voidoids thrived on, their ability to cut loose and let their unbounded energy drive them.

The album bursts right out of the gate with the jagged discord of Quine’s opening guitar line in “Love Comes In Spurts.” Hell comes loose, stringing out yelps over the simple guitar-bass-drums attack set by the Voidoids, as Quine’s guitar wobbles drunkenly through fills during the hook, following Hell’s suit and coming unhinged on the guitar solo. It’s gleefully dissonant in his spirited delivery, with a certain menace to it. It’s almost demented, a jittery, 2 minute, art punk masterpiece.

Slower cuts like “Betrayal Takes Two” still feel unadulterated, but here, Hell’s voice is less acidic than on the others. You can see glimmers of pain in his delivery, contrasting that with some of Quine’s best, most abrasive guitar work on the album. Piercing through the molasses-like waltz, it’s on “Betrayal” that Quine truly comes into his own. His instrument shrieks, screeches, and blares through the backbone of Bell’s cymbals and Julian’s loping bass, a criminally underrated guitar performance every bit as good the best of Television’s work.

There’s no better distillation of The Voidoids’ sound, however, than the immortal title track, now a punk standard. Julian’s iconic, Who-resembling guitar intro sets the tone, as the bass and Quine’s electric join in. Bell’s ride cymbals change the direction, as Hell starts the vocal performance of a lifetime. His delivery is electric, a slight, drunken wail in his voice. The hook stands as a microcosm of the era of punk it was in, a refusal to submit to the expectations of the generations preceding it, a bold proclamation of autonomy that feels exhilarating even today. “Blank Generation” is anthemic and liberating, the battle cry of a genre built on active rebellion.

It only seems right that a band as impulsive and as electric as The Voidoids would burn out as fast as they showed up. Julian and Bell, the latter a future member of the Ramones, departed soon after the release of Blank Generation, leaving only Quine and Hell, who would find some new band members and release one more album as The Voidoids, the grossly underrated Destiny Street. After this, Hell renounced music for good and disappeared (though he has popped up now and then, doing things like writing an essay about Danish post-punk band Iceage), while Quine would work extensively with Lou Reed, among others, before committing suicide from a heroin overdose in 2004. However, the potency and visceral impact the quartet would achieve on Blank Generation is still, in all of punk, unmatched.

by Raghav Raj