Nothing Less Than A Cultural Revolution: Damon Albarn – The Nearer The Fountain, More Pure The Stream Flows (2021)

Amitav Ghosh‘s The Great Derangement (2016) is one tremendous book which examines the question why climate change is not being reflected in contemporary literature and modern art in general. It would be impossible to summarize Ghosh’s elaborate and nuanced thought lines in just a few paragraphs: the Indian writer takes his reader on a journey through enlightenment and industrialization, and the people’s inevitable disconnection from nature, spirituality, and the human family during the various incarnations of Western imperialism. It is an excursion through the new sciences and rationality leading to self-centered and hyper-individualistic modern existences within the secular church of democracy that was exported all over the world; and the consequent abandonment of a non-verbal, spiritual, even super-natural vocabulary which used to connect humans to nature’s pulse and make them express it through art.

Future generations will be deeply irritated, if not shocked by the amnesia and collusion which is reflected in the scathing absence of the climate catastrophe in our literary narrations. Our literature cannot imagine climate change to this day and in addition has constrained itself by both the modern detachment from nature in the age of capitalism and colonialism, and elitist classifications that have kicked ‘catastrophic’ genres like science fiction out of the circle of so called “serious literature”. In terms of relevance, science fiction authors like Philip K. Dick and J.G. Ballard beat every highly acclaimed modern novelist. But nonetheless science fiction is not entirely satisfactory either, as it all too often decouples catastrophes from the Earth and invents new planets and creatures to express them.

But what applies to literature, also applies to other fine arts such as music. In modern music, the big topics of our time -like climate change, imperialism, mass surveillance and crypto-fascism- are largely absent, thus giving it a hyperreal quality. Or the few publications dealing with it are sketchy and bear no relation to the total published mass of music. Amitav Ghosh raises an important suspicion: „Is it possible that the arts and literature of this time will one day be remembered not for their daring, nor for their championing of freedom, but rather because of their complicity in the Great Derangement? Could it be said that the ‘stance of unyielding rage against the official order’ that the artists and writers of this period adopted was actually, from the perspective of global warming, a form of collusion? Recent years have certainly demonstrated the truth of an observation that Guy Debord made long ago: that spectacular forms of rebelliousness are not, by any means, incompatible with a smug acceptance of what exists… for the simple reason that dissatisfaction itself becomes a commodity‘ “. Just think of the dying British Empire of the 1970’s and 1980’s, and how it managed to re-brand itself culturally with a heroic and rebellious working-class image through the social realism of British film and punk. But while labour and miner’s strikes got immortalized in countless films and songs, coal itself and the colonial resource exploitation in many parts of the world was not thematized.

In Culture and Imperialism, Edward W. Said lays out how besides political and economic actions, literature controlled by state agency promotion became European imperialism’s most effective tool for dominating other cultures. Frances Stonor Saunders’ The Cultural Cold War: The CIA and the World of Arts and Letters is a comprehensive US Empire-centered read on this matter which lays out how the CIA not only infiltrated and defined the world’s literary canon, but also the music and film industry- not to speak of the blunt installment of abstract expressionism as leading modern art form to counter the social realism favored by the Soviet Union. Empire’s gonna empire, and it has all resources to build a cultural image which gives a false illusion of inherent progressiveness and rebellion.

There is no effective way to think and fight climate change without talking about Western imperialism. There is no way to fight climate change while the colonial exploitation of the world is going on, while millions of civilians are killed, oil fields are being seized, territories being occupied in the Middle East… But while some artists might well have wanted to deal with climate change within their work, a historical reluctance to talk about Empire is dooming them to the unsubstantiality and irrelevance that many of us are starting to perceive in arts. And things only got worse since this reluctance is joined by a new fear of repressions like the highly opaque algorithmic oppression of art and the written word in the digital age.

So: are there any artists with big audiences who have made music about the destruction of the planet in the last 2 or 3 decades- not through cryptic lyrics and instrumental pieces which are given context by accompanying texts and pictures, but in a non-abstract and interpretatively clear way? Shockingly, I can only think of the walking autoimmune civilization disease incarnate, the great Michael Jackson. Jackson penned a pathetic but extremely clear testimony on climate change and its related causes and consequences with his “Earth Song” and lyrics such as, “Did you ever stop to notice / All the children dead from war / Did you ever stop to notice / This crying earth, these weeping shores /…/ What about the seas? / The heavens are falling down / I can’t even breathe /…/ What about nature’s worth? / It’s our planet’s womb / What about animals? / Turned kingdoms to dust / What about forest trails? Burnt, despite our pleas /…/ What about the holy land? / Torn apart by creed?“ When Jackson performed the song at the Brit Awards in 1996, Jarvis Cocker crashed the King of Pop’s performance to famously waggle his skinny butt at the audience. While I love Jarvis and cheered his action at the time happening, it is a disruption that didn’t age well over time but appears deeply cynical- although one has to be fair to point out that the Pulp singer was appalled by the pathos-filled Jesus-like stage performance by Jackson. But underlying that irritation is also the hubris and resistance to imagine misery beyond subjective and psychological lines, and the sense of humiliation and outrage that settles when being associated with climate and war sufferings as a present condition and future prospect for European and American societies- because miserable suffering belongs to Africa and other “shit-holes”.

Freakish and deranged in his looks and behaviour, Jackson doesn’t serve well as hero, but it is him that will go down as probably the first and lone eco-warrior with a huge audience in pop-history (“Earth Song” has 300 Mio views on YouTube so far). But an unlikely successor with very different qualities was sitting in the Brit Awards audience that night: Damon Albarn, the young man in Fred Perry shirts who wrote and recorded “Girls & Boys” with Blur 25 years ago. The most melancholic voice in Western music moved on to develop into an amazing pan-continental artist and was crowned a Local King of Mali in 2016 for his support and contributions to Mali music. The well-traveled Albarn brought to life countless other international music projects and on top formed another massively successful group with the Gorillaz. The virtual group manifested climate change on their insanely eclectic Plastic Beach (2010), an album which combines the dystopia of a collapsed nature with the glimmers of hope that such a ravaged, yet also post-imperial landscape carries within itself. Albarn stated that a walk on the beach next to his house was the inspiration for Plastic Beach, „I was just looking for all the plastic within the sand“. But what makes Plastic Beach not simply a “green” album but a snapshot of our world is that imperial themes are scattered over the entire album: „”White Flag” was recorded in Beirut, around the end of March 2009. Over there, The Israelis like to fly their jets really low over the city once a month. It’s called “sabre-rattling”. If they fly low and fast enough, it creates a sonic boom effect, taking out all the windows in the area. This faintly surreal experience in Beirut and Syria got rolled into various themes on the album.” In 2001, Albarn actively campaigned and protested against the impending US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq with a British participation under Tony Blair. But with the exemption of Robert Del Naja of Massive Attack, other British artists who you would associate with being anti war were reluctant to take a stand. Damon Albarn’s conclusion of this matter can be regarded as one exemplary starting point for Amitav Ghosh’s The Great Derangement: „I think in this case the only reason we went to war was the result of our individual apathy in the end.“

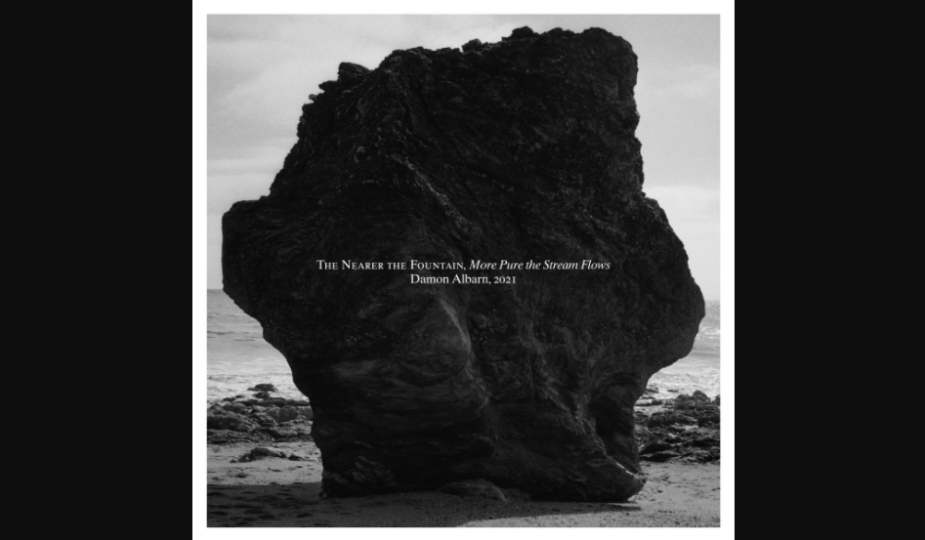

After picking up how the digital invaded all aspects of our lives including the most private ones with his first solo album Everyday Robots (2014), Albarn dropped the title song of his upcoming second solo album The Nearer The Fountain, More Pure The Stream Flows (November 2021) on June 22. It is an ambient song of overwhelming beauty which has the contemplative power and pureness to stop the world for a moment and make it spin gently out of time for its duration. Still, this is a limited vocabulary that doesn’t do the song justice. Underneath the mourning layers of loss and transience, there unfolds a Sufi ambience and an artist who is in a Mugham tradition: full of cosmic nourish, connected with the energy of a mystical and divine dimension, and bearing witness of an ancient stream and its narratives. And while the Western-trained ear and conscience impulsively interprets the introspective of a private love into the song, it turns out that its title is taken from John Clare‘s poem Love and Memory. Clare, also labeled “the poet of the environmental crisis 200 years ago“, witnessed a period of massive changes as the distressing Industrial Revolution swept Europe and made for a destruction of nature and a centuries-old way of life that Clare celebrated in his poems.

It becomes clearer with every release that Damon Albarn is not just another musician exercising in cosmopolitan jams and worldly pastiche, but an artist who stands in an ancient tradition. The Nearer The Fountain, More Pure The Stream Flows is a descriptive title- purified of the artificial complexity evoked by Earth-detachment and the great derangement, Albarn is so close to the fountain now that he flows in the stream of the true avant-garde and artistic elite: connected, seeing, cosmic.

by Saliha Enzenauer

[…] in-depth about the opening title song and why it’s nothing less than a cultural revolution (read here), “The Cormorant“ is pure Bowie in its vocals and distorted ballad quality, and “Royal […]