How Did Elvis Get Turned Into a Racist?

One of the songs Elvis Presley liked to perform in the ’70s was Joe South’s “Walk a Mile in My Shoes,” its message clearly spelled out in the title.

Sometimes he would preface it with the 1951 Hank Williams recitation “Men With Broken Hearts,” which may well have been South’s original inspiration. “You’ve never walked in that man’s shoes / Or saw things through his eyes / Or stood and watched with helpless hands / While the heart inside you dies.” For Elvis these two songs were as much about social justice as empathy and understanding: “Help your brother along the road,” the Hank Williams number concluded, “No matter where you start / For the God that made you made them, too / These men with broken hearts.”

In Elvis’s case, this simple lesson was not just a matter of paying lip service to an abstract principle.

It was what he believed, it was what his music had stood for from the start: the breakdown of barriers, both musical and racial. This is not, unfortunately, how it is always perceived 30 years after his death, the anniversary of which is on Thursday. When the singer Mary J. Blige expressed her reservations about performing one of his signature songs, she only gave voice to a view common in the African-American community. “I prayed about it,” she said, “because I know Elvis was a racist.”

And yet, as the legendary Billboard editor Paul Ackerman, a devotee of English Romantic poetry as well as rock ’n’ roll, never tired of pointing out, the music represented not just an amalgam of America’s folk traditions (blues, gospel, country) but a bold restatement of an egalitarian ideal. “In one aspect of America’s cultural life,” Ackerman wrote in 1958, “integration has already taken place.”

It was due to rock ’n’ roll, he emphasized, that groundbreaking artists like Big Joe Turner, Ray Charles, Chuck Berry and Little Richard, who would only recently have been confined to the “race” market, had acquired a broad-based pop following, while the music itself blossomed neither as a regional nor a racial phenomenon but as a joyful new synthesis “rich with Negro and hillbilly lore.”

No one could have embraced Paul Ackerman’s formulation more forcefully (or more fully) than Elvis Presley.

Asked to characterize his singing style when he first presented himself for an audition at the Sun recording studio in Memphis, Elvis said that he sang all kinds of music – “I don’t sound like nobody.” This, as it turned out, was far more than the bravado of an 18-year-old who had never sung in public before. It was in fact as succinct a definition as one might get of the democratic vision that fueled his music, a vision that denied distinctions of race, of class, of category, that embraced every kind of music equally, from the highest up to the lowest down.

It was, of course, in his embrace of black music that Elvis came in for his fiercest criticism. On one day alone, Ackerman wrote, he received calls from two Nashville music executives demanding in the strongest possible terms that Billboard stop listing Elvis’s records on the best-selling country chart because he played black music. He was simply seen as too low class, or perhaps just too no-class, in his refusal to deny recognition to a segment of society that had been rendered invisible by the cultural mainstream.

“Down in Tupelo, Mississippi,” Elvis told a white reporter for The Charlotte Observer in 1956, he used to listen to Arthur Crudup, the blues singer who originated “That’s All Right,” Elvis’s first record. Crudup, he said, used to “bang his box the way I do now, and I said if I ever got to the place where I could feel all old Arthur felt, I’d be a music man like nobody ever saw.”

It was statements like these that caused Elvis to be seen as something of a hero in the black community in those early years. In Memphis the two African-American newspapers, The Memphis World and The Tri-State Defender, hailed him as a “race man” – not just for his music but also for his indifference to the usual social distinctions. In the summer of 1956, The World reported, “the rock ’n’ roll phenomenon cracked Memphis’s segregation laws” by attending the Memphis Fairgrounds amusement park “during what is designated as ‘colored night.’”

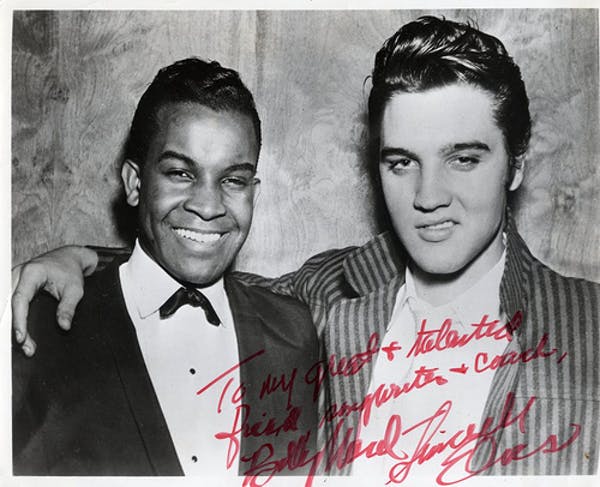

That same year, Elvis also attended the otherwise segregated WDIA Goodwill Revue, an annual charity show put on by the radio station that called itself the “Mother Station of the Negroes.” In the aftermath of the event, a number of Negro newspapers printed photographs of Elvis with both Rufus Thomas and B.B. King (“Thanks, man, for all the early lessons you gave me,” were the words The Tri-State Defender reported he said to Mr. King).

When he returned to the revue the following December, a stylish shot of him “talking shop” with Little Junior Parker and Bobby “Blue” Bland appeared in Memphis’s mainstream afternoon paper, The Press-Scimitar, accompanied by a short feature that made Elvis’s feelings abundantly clear. “It was the real thing,” he said, summing up both performance and audience response. “Right from the heart.”

Just how committed he was to a view that insisted not just on musical accomplishment but fundamental humanity can be deduced from his reaction to the earliest appearance of an ugly rumor that has persisted in one form or another to this day. Elvis Presley, it was said increasingly within the African-American community, had declared, either at a personal appearance in Boston or on Edward R. Murrow’s “Person to Person” television program, “The only thing Negroes can do for me is buy my records and shine my shoes.”

That he had never appeared in Boston or on Murrow’s program did nothing to abate the rumor, and so in June 1957, long after he had stopped talking to the mainstream press, he addressed the issue – and an audience that scarcely figured in his sales demographic – in an interview for the black weekly Jet.

Anyone who knew him, he told reporter Louie Robinson, would immediately recognize that he could never have uttered those words. Amid testimonials from black people who did know him, he described his attendance as a teenager at the church of celebrated black gospel composer, the Rev. W. Herbert Brewster, whose songs had been recorded by Mahalia Jackson and Clara Ward and whose stand on civil rights was well known in the community. (Elvis’s version of “Peace in the Valley,” said Dr. Brewster later, was “one of the best gospel recordings I’ve ever heard.”)

The interview’s underlying point was the same as the underlying point of his music: far from asserting any superiority, he was merely doing his best to find a place in a musical continuum that included breathtaking talents like Ray Charles, Roy Hamilton, the Five Blind Boys of Mississippi and Howlin’ Wolf on the one hand, Hank Williams, Bill Monroe and the Statesmen Quartet on the other. “Let’s face it,” he said of his rhythm and blues influences, “nobody can sing that kind of music like colored people. I can’t sing it like Fats Domino can. I know that.”

And as for prejudice, the article concluded, quoting an unnamed source, “To Elvis people are people, regardless of race, color or creed.”

So why didn’t the rumor die? Why did it continue to find common acceptance up to, and past, the point that Chuck D of Public Enemy could declare in 1990, “Elvis was a hero to most… straight-up racist that sucker was, simple and plain”?

Chuck D has long since repudiated that view for a more nuanced one of cultural history, but the reason for the rumor’s durability, the unassailable logic behind its common acceptance within the black community rests quite simply on the social inequities that have persisted to this day, the fact that we live in a society that is no more perfectly democratic today than it was 50 years ago. As Chuck D perceptively observes, what does it mean, within this context, for Elvis to be hailed as “king,” if Elvis’s enthronement obscures the striving, the aspirations and achievements of so many others who provided him with inspiration?

Elvis would have been the first to agree. When a reporter referred to him as the “king of rock ’n’ roll” at the press conference following his 1969 Las Vegas opening, he rejected the title, as he always did, calling attention to the presence in the room of his friend Fats Domino, “one of my influences from way back.” The larger point, of course, was that no one should be called king; surely the music, the American musical tradition that Elvis so strongly embraced, could stand on its own by now, after crossing all borders of race, class and even nationality.

“The lack of prejudice on the part of Elvis Presley,” said Sam Phillips, the Sun Records founder who discovered him, “had to be one of the biggest things that ever happened. It was almost subversive, sneaking around through the music, but we hit things a little bit, don’t you think?”

Or, as Jake Hess, the incomparable lead singer for the Statesmen Quartet and one of Elvis’s lifelong influences, pointed out: “Elvis was one of those artists, when he sang a song, he just seemed to live every word of it. There’s other people that have a voice that’s maybe as great or greater than Presley’s, but he had that certain something that everybody searches for all during their lifetime.”

To do justice to that gift, to do justice to the spirit of the music, we have to extend ourselves sometimes beyond the narrow confines of our own experience, we have to challenge ourselves to embrace the democratic principle of the music itself, which may in the end be its most precious gift.

by Peter Guralnick

(Originally published in The New York Times in Aug. 11, 2007. Peter Guralnick is the author of the only Elvis Presley biography that matters:

Pt. 1: Last Train to Memphis: The Rise of Elvis Presley & Pt. 2: Careless Love: The Unmaking of Elvis Presley.

“Unrivalled… Elvis steps out of these pages, you can feel him breathe, this book cancels out all others.” – Bob Dylan)

[…] read: How did Elvis get turned into a racist? by Peter […]