Paul’s Boutique At 30

At the rate that they were going, The Beastie Boys were destined to flame out. With Adam ‘MCA” Yauch, Michael “Mike D” Diamond, and Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz all doing their best semi-ironic frat boy impressions, their 1986 Def Jam debut, Licensed To Ill, was forceful and blustering, helmed by the meaty guitars and punchy drums of in-house producer Rick Rubin. It had been released to great fanfare, promptly becoming the first rap record to sit atop the Billboard 200. What’s more, it was a major catalyst in moving rap past novelty status in the eyes of White America, an appeal that played no small part in it becoming the best-selling rap record of the 80’s.

But with the wave of success came controversy. As hits like “Fight For Your Right (To Party)” and “No Sleep Till Brooklyn” gained more radio play and MTV exposure, they quickly opened up the trio to criticism from all sides; they were called out for their misogyny, homophobia, and crass behavior from the suburban crowds that they were bringing hip-hop to, and hip hop purists stuck their noses up at the notion of three white, Jewish kids being America’s first taste of the genre. These criticisms were compounded by a chaotic tour the following year: go-go dancers in cages, a massive, 20 foot hydraulic penis, all culminating in Horovitz getting arrested for hitting a crowd member with a can of beer.

As the tour was coming to a close, the trio was becoming more and more disillusioned with the fame and luxury they had been thrust into. As Horovitz writes in The Beastie Boys Book, “[We] became what we hated… sloppy drunk dudes trying to creep on young women.” What’s more, Rubin and Def Jam were beginning to exercise more creative control on the group, something that rubbed the band, especially Yauch, who was beginning to understand more about experimentation in the studio, the wrong way (Yauch would quit for a short period of time, spurred by a frustration of always being “the drunk guy at the party” and not being able to express his creative vision.) At one point, a concept film with the band was proposed where only 10% of the profits went to them, an offer which incensed all three members. With the royalties of License to Ill being pocketed by label-heads Rubin and Russell Simmons, and Simmons trying to strong-arm the group into another record to capitalize off of their success, the Beasties felt that the only option was to change lanes, departing from Def Jam and heading west.

They found themselves in Los Angeles in 1988, eventually signing to Capitol Records in a move that drew even more disdain from New York diehards. When the trio visited Delicious Vinyl founder Matt Dike’s apartment, Dike slipped the group a few sampledelic instrumental demos from a local production duo of Michael Simpson & John King, a.k.a. the Dust Brothers, facilitating the fruitful collaboration that’d emerge from the two. Ignoring Capitol’s desire for an album as soon as possible, The Beastie Boys and Dust Brothers convened in Dike’s living room with engineer Mario Caldato, traded in their cans of beer for cheeba and dust, and set out to make a record that fulfilled their newfound experimental zeal.

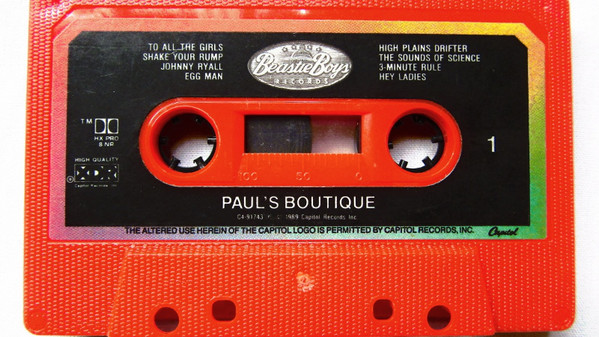

The result of these sessions would become their 1989 sophomore effort, Paul’s Boutique, a daring, fearlessly brilliant record that stands as one of the finest hip-hop records ever made.

The first thing that anyone talks about when mentioning Paul’s Boutique is the Dust Brothers’ production. And for good reason, too; the record is a masterclass in sampling, weaving over 100 snippets of sound into a tightly knit musical collage that takes as much from soul as it does from heavy metal. The duo had been planning to send their instrumental creations to clubs, but as Yauch would later say, “they were quite surprised when we said we wanted to rhyme on it, because they thought it was too dense.” It results in a song like “Shake Your Rump” which tosses 14 different samples in and out of the mix, breaking down a jagged funk bassline one second and drowning in clanging percussion the next. The lead single, “Hey Ladies” ravages several disco records for the beat, a cowbell-filled gem with a fantastic video to match. The Beatles get thrown into a blender on the show-stopping two-parter “The Sounds Of Science” from the sing-songy build-up backed by a chop of “When I’m Sixty-Four” to the release, where a riff from “The End” and the drums from Sgt. Pepper’s reprise join for one of the most euphoric moments on the record (not to mention lyrical snippets from KRS One and Pato Banton). The kitchen-sink production still sounds unprecedented, an irreproducible patchwork of sound that gets more and more fascinating with each listen.

And then, of course, there’s the rapping. In the past, The Dust Brothers had worked with Tone Loc and Young MC, rappers who weren’t capable enough to act as a commanding presence on the duo’s layered beats. The Beastie Boys were different, maneuvering deftly through the soundscapes, armed with an undeniable rapport and unbounded energy. When they weren’t bouncing in and out of each-other’s sentences, like on the delightfully funky “What Comes Around” or on the triumphant “Shadrach” they showed that they could each command a mic with their own distinct presence. On “3-Minute Rule” one of the looser songs here, the trio all take their own shot at a standalone verse; Mike shoots the shit and throws in a few boasts, Yauch tackles the expectations surrounding the group, and Ad-Rock mocks the trappings of Hollywood and high society. The song is one of the simplest on the record, but it’s a remarkably masterful display from each of the three MC’s.

While the lyrics here don’t completely abandon the lyrical themes of Licensed To Ill, they’re leaps and bounds ahead, filling crevices with rapid-fire punchlines and pop-culture references. Take “High Plains Drifter” a vivid odyssey following a nihilistic kleptomaniac, name-dropping Travis Bickle, Dirty Harry, and Steve McQueen as he shoplifts at K-Mart, robs a 7/11, runs over mailboxes, and escapes jail with a stolen car. It’s layered, reference-laden, and an absolutely enthralling tale. There’s the raging “Looking Down The Barrel Of A Gun” undoubtedly the most intense song here, an ominous, ambiguous barrage of threats delivered under bracing guitars and suffocating percussion. “Johnny Ryall” takes a more lighthearted tone, a character portrait of a misfortunate bum with a fresh Gucci watch. Then of course, there’s the brilliant “Egg Man” which elevates something as juvenile as egging someone to new heights with some more Beatles references and a surprising profundity for the takes made on race, the crack epidemic, and life as a whole. The song is driven by a fantastic bassline and a rotating stream of terrific sound effects, including (but not limited to) the Jaws theme, the Psycho theme, the theme from Superfly, and various snippets of Chuck D. It’s delightfully energetic, especially when they explode out of a spoken-word snippet (“We’re all, dressed in black…”) in one of the best moments on the record.

Some may argue that Paul’s Boutique peaks at “B-Boy Bouillabaisse” which swirls in a beatboxed freestyle, a tribute to Jamaica Queens, a breathless solo exhibition from MCA, and an all-consuming, bass-boosted bounce behemoth, into a stellar 12-minute closing suite, but I’d argue that the apex of the record’s sound comes in the form of “Car Thief”. Built from a layer of brilliantly trippy funk samples, the song oozes a nocturnal cool, constantly enveloped in a haze of smoke. Comparing style biters to car thieves, it takes the cake for some of the best bars here; the way the song kicks off (“Some static started…”) is brilliant, as is the way the beat shifts as the cops in the story arrive. With fantastic scratching interludes and a gorgeous outro, “Car Thief” is the heart of Paul’s Boutique, the sound of the Beastie Boys coming into their own as lyricists, rappers, and above all, artists.

Of course, most fans really didn’t care for the record. Their only taste of the Beastie Boys had been through MTV and radio, and other than the video of “Hey Ladies” getting some airplay, nothing from the record had really blown up for the trio. Paul’s Boutique flopped on release, only reaching the 14th spot on the Billboard 200, leading to mass firings at Capitol and little to no marketing for the record. For the longest time, people regarded the record as a failure, a damning of the Beasties as one hit wonders.

It’s safe to say that history has been kinder. Paul’s Boutique stands today as the Beastie Boys’ magnum opus, one that took the free reign of sampling in hip-hop’s golden age and pushed it as far as it could. It’s one of the most influential hip-hop records ever, recognized by everyone from Miles Davis, who said he “couldn’t stop listening to it,” to Chuck D of Public Enemy himself, who was quoted as saying that “the dirty secret among the Black hip hop community at the time of the release was that Paul’s Boutique had the best beats.” A high water-mark for the Beastie Boys, Dust Brothers, hip-hop, and sampling itself, Paul’s Boutique sounds fantastic, even 30 years later. It remains in a league of its own, an unsurpassable, inimitable masterpiece.

by Raghav Raj

Saw the post on IG, really great article and this was one of my cassettes always in rotation my senior year of high school and freshman year of college.

Great review. It’s been a few years since I’ve listened, going to have to revisit this now! Thorough analysis, interesting facts, a well written article all around. Thank you.

Their best album! I remember how it bombed back in the day, great to see it getting the recognition it deserves.

Where did Miles Davis say this? Do you have a source? I cannot find it, thank you.

Amazing write up of possibly the best Beastie Boys album in my opinion. Loved reading this. Wasn’t aware of Miles Davis love for it either. Excellent info!!