Apocalyptic Gospel, Existential Doom & Blasphemious Grooves: The Story of Orhan Gencebay, Turkey’s Best Kept Secret

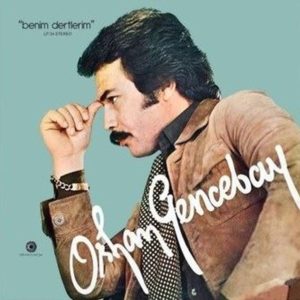

We will deal with another heavyweight of Turkish music today, one who refuses the genre name ‘Arabesk’ for being „inadequate and uncomplete“, and prefers labels such as ‘Progressive Turkish Music’ or simply: ‘Gencebay Music’.

Orhan Gencebay has officially sold 80 million records in Turkey- which already makes him one of the most succesful artists on this planet- but it is estimated that the number is around 200 million together with bootleg sales, considering that illegal production sales are estimated to be about 2 times higher than legal productions in Turkey. And this number still doesn’t count in the bootleg sales of Orhan Gencebay in the vast Middle East, where he is also a star.

Orhan Gencebay has officially sold 80 million records in Turkey- which already makes him one of the most succesful artists on this planet- but it is estimated that the number is around 200 million together with bootleg sales, considering that illegal production sales are estimated to be about 2 times higher than legal productions in Turkey. And this number still doesn’t count in the bootleg sales of Orhan Gencebay in the vast Middle East, where he is also a star.

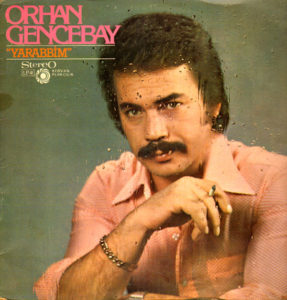

Orhan Gencebay, or ‘Orhan Baba’ as his fans call him, was born in the Black Sea area of Turkey in 1944. At the age of six, he started taking violin and mandolin lesson, one year later he started studying Turkish folk music and learning to play its main instrument, the saz, of which he became a great virtuoso. Aged 14, he wrote his first professional composition (of more than 1000) and called it ‘An Eternal Flame Trembling in My Soul‘, and started to engage in jazz and rock music, playing tenor saxophone in various Western influenced orchestras and in the army during his military service.

His extraordinary talent led him to Istanbul, where he started to work as musician for the public broadcaster TRT, from where he left after 10 months on the grounds that “the musical understanding of the institution was not in favor of progression and experimental enough”. Afterwards, Gencebay started to play the saz for other artist’s productions and worked as a musical director for many Turkish ‘Yesilcam’ films, and later also took the lead role in 35 films himself.

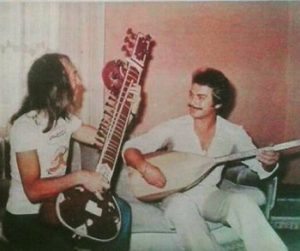

He released his first record in 1968, became a partner to Turkey’s leading  record company Istanbul Plak in 1971, and one year later founded his own label Kervan Plak, Turkey’s first domestic record company (Türküola was founded by Turkish immigrants in Cologne, Germany in the 60s). Kervan Plak signed many artists from different genres, like Anatolian Rock legend Erkin Koray, who became a close friend, and whose song ‘Hor Görme Garibi‘ f.e. is a Gencebay composition and production.

record company Istanbul Plak in 1971, and one year later founded his own label Kervan Plak, Turkey’s first domestic record company (Türküola was founded by Turkish immigrants in Cologne, Germany in the 60s). Kervan Plak signed many artists from different genres, like Anatolian Rock legend Erkin Koray, who became a close friend, and whose song ‘Hor Görme Garibi‘ f.e. is a Gencebay composition and production.

During the 1960’s and 70s, Gencebay released many singles in his new genre that is a fusion of traditional Turkish folk music, Turkish classical music, Western classical music, jazz, rock, country, progressive, psychedelic, Indian, Arabic, Spanish, and Greek music styles. Remeber- that was a time where Beatles and Stones fans would rave over a single sitar being played on those bands’ albums. Sgt. Pepper is not able to thrill you as Gencebay fan.

Gencebay is 100% musician and 0% interested in the showbiz and entertainment aspect of his art- despite his massive success, he refused the stage and never played live for 44 years: “I’m a bit shy, and I am shy playing in front of people. I also have the fear that if I took the stage, it could take away from my inner happiness.” This absence from stages is completely in line with Gencebay’s flawlessly dignified and honorable detachment in his public appearance. He only broke with his tradition in 2005, when he performed ‘Hatasiz Kul Olmaz‘ for the Einstürzende Neubauten‘s Axel Hacke and his documentary Crossing the Bridge.

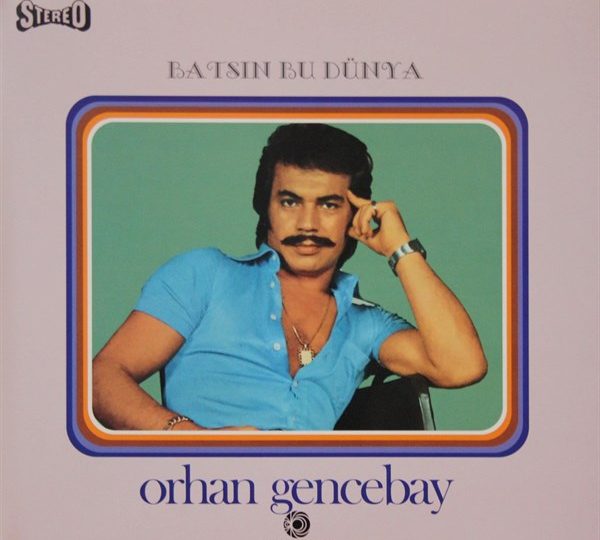

Without much further ado, we will now have a closer look at Orhan Gencebay’s 30 million copies selling masterpiece ‘Batsin Bu Dünya‘, an unparallelled gospel of existential doom with a blasphemious groove. During these 5:35 minutes, we are witnessing a general existential accusation that culminates in an explosive dialogue with God, the creator. ‘Batsin Bu Dünya‘ is an exercise in prayer for those who have tasted the hard and merciless fist of God more than once, an apocalyptic dance into ruin.

The song starts with a needling organ and stabbing existential strings, which visually can only be translated into a picture of crouching naked in the corner and shivering while rain is pounding on you. Your ribs may appear very precisely under the skin of your back. A relentlessly shrill groove that pushes you forward like the taser the cattle, the intro ends with an acoustic Spanish chord, which in this context sounds like a defiant invitation to High Noon between the servant and his creator.

Gencebay wastes no time to express his state of mind and heart, with his first words being ‘Shame on you!’ on repeat: “Shame on you / Shame on you / Shame on such a fate / Everything is dark, where is the humanity? / Shame on those who serve to a servant.“

While not adressed to God directly, Gencebay makes clear what he thinks of the questionable fate the creator has unleashed on him. Darkness and misery have fallen on him long before yesterday, darkening the forest of life in a way which makes it impossible to see through it anymore. The blasphemous level is still very mild at this point, and Gencebay balances things by addressing the lack of humanity, and the human’s inclination to serve worldly idols and kings- a line he delivers with the most unforgettable intonation and over-articulated like a dry spit.

Delivered by a his trademark opiodesque velvet voice, the composedness and calm is deceptive. Set off by an oriental belly-dance beat, which is nothing less than the crazy and rapturous dance into ruin here, Gencebay calls for the destruction of all things when he moves on into the doomed chorus after little preparation:

Let this world go down, let this dream end

Unborn ordeals, troubles not yet lived through,

The longing heart- should it all be mine?

Fate, what have I done to you?

You condemned me to myself,

There are a thousand complaints in every breath.

My complaint is to the creator,

my complaint is to the creator.

From the rather understandable questioning of bad destiny, Gencebay moves on to a more precise yet very twisted accusation in the second half of the chorus: You condemned me to myself- which, once you read it, is suddenly clearly the worst possible kind of condemnation. It is a strange call for salvation which avoids asking for it. Because it is at the same time an attempt to place yourself outside of divine creation and providence, which can be a great source for suffering and humiliation due to the irrefutable imbalance of forces. Gencebay doesn’t care – My complaint is to the creator– and introduces us to the next chapter with these words: our apocalyptic rider is challenging God directly now.

Is it you or me who got confused- I couldn’t understand

You gave me such trouble, I couldn’t recover from it

I’m in a dead-end street, I couldn’t find my way

Uff… uff… uff… uff…

„Is it you or me who got confused?“– this is a different kind of prayer, with every word detonating on your tongue when spoken out loud. Gencebay wants to grab God and asks him if he is still quite right, or if ‘confusion’ is an attribute that should be considered when trying to understand his divine plan, which often reveals itself in cruelty, misery, and injustice. It is of course the eternal trap of trying to attribute God, just turned around now. While most prefer to emphasize on God’s ‘love and forgiveness’ and blend out his punishing qualities in expectation of a self-fulfilling invocation of redemption, Gencebay concentrates on the exact opposite when ‘fate hits the fan’- enough is enough, and some questions should be allowed.

Was I the one who created?

Was I the one who created?

Worries and troubles, was it me who created these things?

If sin has turned into joy, if loyalty is exhausted

If order is disrupted- was it me who created?

Let this world go down, let this dream end

Shame on my life passing without love

Very complex questions are being dealt with here, which makes this blasphemous gospel more valueable than most superficial prayers which have abandoned the confrontation and fear of God, and the sophisticated theological field it leads us into. But doubt is a logical reaction to ‘fateful’ torture and just another form of inner-action and debate, one that can ultimately give you the decisive advantage in questions of enlightenment and belief.

Gencebay describes the place that gave birth to the song: “Batsın Bu Dünya” is Turkey’s elegy. Fact is that the ’70s were very bad years. It is Turkey’s lament. The song to cry with.” The song indeed became a massive hit and remains cult among Turks to this day. But during the years around the 1980 coup, after which the military government would ban mainly socialist artists and their songs, Gencebay’s song also got banned for several years because it “rebels against the existing (universal) order and disrupts people’s mood with its darkness” (this was the same anti-blasphemous government that banned women from wearing headscarves in schools and universities- in a 95% Muslim country). The public broadcaster TRT stopped promoting the old masters like Gencebay on their channels, and replaced them with less sophisticated starlets. Quality decreased.

Gencebay remembers: “The injustice done to me regarding bans in the history of the Republic of Turkey is unparalleled. And it is necessary to add that TRT’s strict rules and taboos marked the biggest blow to the development of Turkish music. Nobody has done more damage than TRT, whether knowingly or unknowingly”. Now it is important to understand that Gencebay was not generally banned, but just banned from the public broadcaster- his records were still allowed, sold and listened to everywhere. Nevertheless, it was an outrageous and in his case especially baseless censorship- but it made me think of how widespread this technique really still is.

Gencebay remembers: “The injustice done to me regarding bans in the history of the Republic of Turkey is unparalleled. And it is necessary to add that TRT’s strict rules and taboos marked the biggest blow to the development of Turkish music. Nobody has done more damage than TRT, whether knowingly or unknowingly”. Now it is important to understand that Gencebay was not generally banned, but just banned from the public broadcaster- his records were still allowed, sold and listened to everywhere. Nevertheless, it was an outrageous and in his case especially baseless censorship- but it made me think of how widespread this technique really still is.

Is there really no such censorship in Western societies, and especially America? Call it a ‘selection’ instead of censorship, and it might not appear so far off anymore. Everytime we turn on the radio, we are exposed to underterrestrial music from horrible charts and an eternal circuit of evergreens from all decades. How many times have you asked yourself why certain music is being pushed and promoted over and over, while other truly great artists and bands simply get no airplay or coverage? Why grunge and not great punkrock from the Gories and New Bomb Turks scene? Why all the supposedly counter-cultural hippie bands that were rather involved with Charles Manson than the anti-war movement, and not, say, the MC5? And who decides this?

We tend to allow ourselves to be fobbed off with the omnipresent and diffuse argument of ‘the markets’, which is never a satisfying explanation, but an easy answer building up kafkaesk castles. One other explanation is that a hidden censorship -or selection- might be pushed on us, while at the same time you exactly hear what you are supposed to hear.

And you know… there can be only one conclusion in the face of all this:

Let this world go down. Let this dream end.

by Saliha Enzenauer