Alim Qasimov – A Spiritual Awakening from Azerbaijan

He’s not well known in the West, but honestly I think he is probably the best singer alive in the world today. Technically and emotionally he is just incredible.

Björk on Alim Qasimovic

One of the most beautiful and powerful things in Muslim culture to me is the call for prayer, the “Ezan” (or Adhan). 5 times a day the muezzin’s voice cracks through the mosque’s speakers and reminds you of a divine entity. „I’m here,“ God seems to say through the hypnotic melody of the Arabic prayers. And even if you don’t believe in a God, the ezan serves as daily invitation to spiritual and cosmic reflection for everybody, an invitation that I miss deeply while living in Europe. Depending on where you are, it is sometimes the crackling sound of just one mosque nearby, or the delicate sound of a distant mosque transmitted through the wind, and most often it’s both- a beautiful interplay of multiple close and distant mosques, all with different voices, never monotonous or perfectly orchestrated; every time newly calibrating your ears in terms of sound, transmission and perception (sample).

It would be exaggerated to state that the call for prayer halts life for all and every time that it’s being heard on crowded streets and bazaars, although everybody is careful to not do the most debased things while it is being heard. Most people move on with their daily business when they hear that common chant which is an integral part of their lives. Yet it can happen that it gets you, especially when you’re already in a contemplative mood. Like with all music and sound, most of the time it was in the evening hours that I felt most perceptive to the ezan and its beauty. While watching the mountainscape and sky on a silent night, or enjoying drinks in warm Mediterranean nights… the ezan would start to play and mystify the entire atmosphere, laying down on you like a graceful mist, a cosmic meditation. The night transmits sound differently, more clearly, and it opens our souls. That’s why we love to listen to music in the car while driving through the night. But it would be wrong to attribute these things to the night and outer forces only, and disregarding our innermost forces for these perceptions: our intellect and the state of our souls.

Haal or ḥāl: an Arabic word that is also commonly used in Persian and in Turkic languages, describing a temporary, transient state of conciousness. It has strong associations with Sufism, the mystical dimension of Islam. In Sufism, hāl is a state of spiritual awakening that creates an openness to the mystical presence of the Divine. It is an universally translatable concept describing spiritual glimpses within the full journey, filled with inspiration, cosmic nourish, and fleeting moments of transformation. It is in such a state, the beautiful ḥāl, where the ezan stops being just a reminder of God but becomes a dialogue, or where a song pierces its way to your core and strips you down, sometimes even brings you on your knees. And ḥāl is the state in which the Azerbaijani musician and Mugham singer Alim Qasimov moves.

Mugham is a highly complex modal folk musical composition from Azerbaijan, particularly rooted in the town of Shusha in Karabakh, which is renowned for this art. According to the New York Times, „mugham is a symphonic-length suite, full of contrasting sections: unmetered and rhythmic, vocal and instrumental, lingering around a single sustained note or taking up a refrain that could be a dance tune.“ It is a free form combining classical poetry with an orally passed collection of melodies and fragments that performers use during their improvisation. Mugham is a widespread intercultural art form in other Near and Far Eastern regions from Transcaucasia to China. The Uighurs in Xinjiang refer to the music as ‘Muqam‘, the Uzbeks as ‘Makom‘ , the Tajiks as ‘Shashmaqam‘, the Turks as ‘Makam‘, the Arabs as ‘Maqam‘ and the Persians as ‘Dastgah‘.

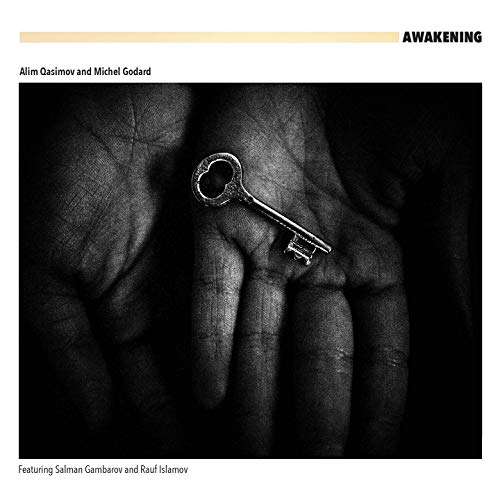

To some known from his duet with Jeff Buckley, Alim Qasimov is widely regarded as the greatest living Mugham singer. “He is completely connected with something else, you can call it what you want: it can be God, energy, creativity, something is coming through him, this is absolutely sure, and to be on stage with him is wonderful. I never felt this so strong.” is how French avant garde jazzman and serpent Michel Godard tries to explain Qasimovic’s ḥāl and unashamedly emotional art. Both artists have collaborated for the album The Awakening (2019), which is an outstanding work in the synthesis of East and West. The accompanying promotional text of the record label Buda Musique raises one question: „It is hopeful music for the future: would the juxtaposition of two cultures be the real avant-garde of our time?“ The answer will always be Yes, especially when considering that the sublime art of Azerbaijani Mughab is already the result of merged and interweaved cultures. A brief history:

“Music in Azerbaijan reflects the long history of contact between Turkic and Iranian peoples in Transcaucasia, the region lying south of the Caucasus Mountains between the Black Sea and the Caspian Sea. In antiquity, the territory of present-day Azerbaijan was part of a succession of Iranian empires, notably the Achaemenian and Sasanian, that was eventually infiltrated and conquered by Turkic and Mongol groups from the east: Ghaznavids, Seljuqs, Ilkhanids, and Timurids. During the 16th -18th centuries, control of Transcaucasia passed back and forth between two imperial rivals: the Ottoman Empire, with its capital in Istanbul, and the Safavid Empire, centered in Iran. At the end of the 18th century, the Qajars, an Iranian dynasty of Turkic origin, emerged as rulers of the formerly Safavid lands, but in 1828, the Qajars were forced to cede their northern provinces, including a part of Azerbaijan, to Russia. Parts of these provinces later became the Soviet Socialist Republic of Azerbaijan, and, following the breakup of the Soviet Union in 1991, the independent nation of Azerbaijan. Southern regions of Azerbaijan remained under Qajar control, and today the number of Iranians who speak Azeri (a Turkic language) or identify themselves as ethnically Azeri is thought to be two to three times the population of Azerbaijan itself, currently around ten million. In traditional Azeri music, Turkic elements are felt most strongly in folk song and epic traditions rooted in the countryside, while Iranian influence has shaped urban court music and art song. Musical instruments in Azerbaijan reflect this division.“

I descend from the Turkish Black Sea region and the Azerbaijani Mugham is highly familiar to me in its instrumentation, feeling, and language, as it is for many Iranians and Turkic folks around the globe practicing the Mugham and related art-forms in their cultures. Yet, cultural similarities cannot be the entire answer, since not everybody of the same culture or religion is equally perceptive to it. In terms of spirituality and openness to this music, we have to apply a broader and more universal explanation. Why is it that a few are able to connect themselves to a cosmic continuum and to experience the state of ḥāl, wide open to avantgarde and spiritual experiences when listening to music, while others are not and settle for more easily accessible emotion in art? Why is it that some- no matter if they are atheists or submitting to an entity- are sensitive and receptive to every opportunity that can make them achieve hāl, this spiritual and transient state of conciousness, and like a Sufi can often consciously switch on that state of spiritual openness in order to reach the related concepts that are ecstasy (wajd), annihilation (istilam), happiness (bast), despondency (qabd), awakening (sahû), or intoxication (sukr)?

Unusual, even controversial for our times of equalizing everything and everyone except the human dignity, Alim Qasimov concludes that there is an elite listener: “Mugham is an elite art, it’s for a select group- for people who have some kind of inner spirituality, who have their own inner world. These days ‘elite’ refers to something more commercial than spiritual, but that’s not what I have in mind. An elite person is one who knows how to experience, how to endure, how to feel, how to listen to Mugham and begin to cry. This ability doesn’t depend on education or upbringing, nor on one’s roots. It’s something else. It’s an elite of feeling, an elite of inspiration. These kinds of listeners aren’t always available.”

This elite is not marked by a canonical taste or vainglorious sonic perception, but is defined by an imprinted spirituality in the perception of all art. And so it happens that a critically acclaimed director like Andrei Tarkovsky has used Azerbaijani Mugham in his transcendental films like Stalker, films that have an elite viewership itself. Tarkovsky, who has studied Arabic at the Oriental Institute in Moscow, seems to paraphrase the definition of hāl when he reflects on how his complex film projects mature: “It is obviously a most mysterious, imperceptible process. It carries on independently of ourselves, in the subconscious, crystallizing on the walls of the soul. It is the form of the soul that makes it unique; indeed, only the soul decides the hidden ‘gestation period’ of that image the conscious gaze can not perceive which“.

In times of sentimentality being confused for spirituality and anti-intellectualism being worn as a badge of honor, new connotations of the elite term are needed. Connotations that captivate through an absence of the material and that oppose a democratic art-understanding which moves on the surface of things and begs for decline, connotations that instead mark the existential searches in the mystical and psychedelic state of hāl and its related concepts like annihilation (istilam). So, if you ever feel like collapsing, then listen to Alim Qasimov and you might end up with your existence shaken to the core. His music puts you in your place, the place you belong to: on the search for the meaning of life.

by Saliha Enzenauer

Live: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cHkXM-i_1MU

[…] the mourning layers of loss and transience, there unfolds a Sufi ambience and an artist who is in a Mugham tradition: full of cosmic nourish, connected with the energy of a mystical and divine dimension, and bearing […]

Hi Saliha. Thank you for this beautiful writing. Alim Quasimov and Mugham are new to me. How heartful is the sound in the sample of this artcle. Already check my nearest recordstore and they have two his albums: ”L’Art du Mugham” and ”Eastern Voices”. I’ll go to listen ( and probably buy) them tomorrow, ehen door will open. Reading this was a great start for this Sunday.

Hi, life in Helsinki is ok. Situation is not so bad here now, so restaurants, theatres etc are open. Kaurismäki’s bar is now in different place than earlier. Here are some gigs, but they are very restricted. Exactly one year ago I was jumping and shouting in Turbonegro’s gig. How’s life there? I hope there’s no evacuations any more in your quarter. It would be awesome if you’ll write from your time in Finland .

Saliha,

Your article enriches the concept and perception that we can have towards any religion, you connected spirituality with art. I believe that spirituality is one of the most transcendental experiences that human beings can live. This particular state of mind makes you reflect and go beyond the social and moral prejudices that we face every day.

The culture that surrounds Alim Qasimov’s magic is completely unfamiliar to me, but from what I’ve read and heard I’m already quite intrigued. I’m just realizing that Alim performed in 2014 in the city of Guanajuato, Mexico (for the “Festival Internacional Cervantino”). I can’t believe I missed his presentation.

On the other hand, I knew very superficially those facts of Tarkovsky. I can say that his films must be carefully appreciated, no filmmaker has connected so much with nature as he did.

Thank you for introducing us to new forms of artistic expression in music, and for showing us how interesting it can be to venture on a historical and philosophical journey when you make the correct use of the influences, experiences and words that are within your reach.

“Spirituality is one of the most transcendental experiences that human beings can live” – and transcendence is one of the greatest states a human being can reach. Unfortunately transcendence is vanishing from all things…

It is always the same with these concerts- it has happened to me so often that I discovered an artist, only to find out that they playeda very special and rare concert in my city before I discovered them 😉 C’est la vie! Hope we both get to see Qasimov one day on our continents!

Thank you for taking the time to comment my article. Art and philosophy is a wonderful journey that never ends and nourishes us, revealing the meaning of all things.

Saliha,

This is a contemplative, cultural, historical, meditative, reflective essay about spirituality in art that I read several times to absorb all of its layers. I mention the adhan or ezan in my short novella I wrote October/November 2016 about Aleppo and the crisis in Syria. There is something about spiritual music, as you said, that is most powerful and resonant during the “magic hour” as the dusk of evening fades into twilight. I listened to the song you shared. Alim Qasimov’s voice contains a profound depth of emotion and a receptivity to the spiritual realm, the same profound depths of emotion and receptivity to the spiritual realm, as you noted, that can be discovered in Andrei Tarkovsky’s cinema. The connection I felt the most in Alim Qasimov’s singing was a mournful sorrow for our world that moved me within the images of the films Baraka and Samsara.

I am intrigued by Rumi and Sufi philosophy, absolutely fascinating article and music. This is great.

Fortunately, I have had that experience of hearing the call to prayer myself and feeling overwhelmed by the sense of transformation and peace that you articulate in your article. The intensity of those emotions and the reflective opportunity is there for anyone who is open to being touched by Allah. Or, as you say, taking the opportunity to reflect. Unfortunately, not everyone does take that opportunity. Even when it is being offered. We talked so often about this elitism. And I couldn’t agree more. It’s not an elitism based on class or vanity. Instead, as you wrote, “ imprinted spirituality in the perception of all art”. That’s a beautiful definition. And an important one.

These are the points in music I so often find myself searching for in the deeper pools of music. In the avant-garde, the free and the complex. It’s reassuring that this is also the platform that God uses for this conversation. It just takes that effort. It’s a beautiful article .

The main rhythm flows like a calm river, the inner rhythm explodes like a volcano. Perfect fusion, it’s an amazing discovery for me. Brilliant article 👌

Greetings from a Kerkuk Turkmeni in Iraq, Alim Kasimov is a piece of heaven on earth. Saliha, your article is beautiful.

One word “excellent”. This is something beyond music, otherworldly. Great article! 🎶

I keep repeating the live video. In what state of emotion is this man? It’s mindblowing.